When Maryam Jillani was growing up in Islamabad, the last day of Ramadan was about more than breaking a month-long fast with extended family.

A joyous occasion, the Eid Al-Fitr holiday also was marked with visits to the market to get new bangles, wearing her best new clothes and getting hennaed. Not to mention the little envelopes with cash gifts from the adults.

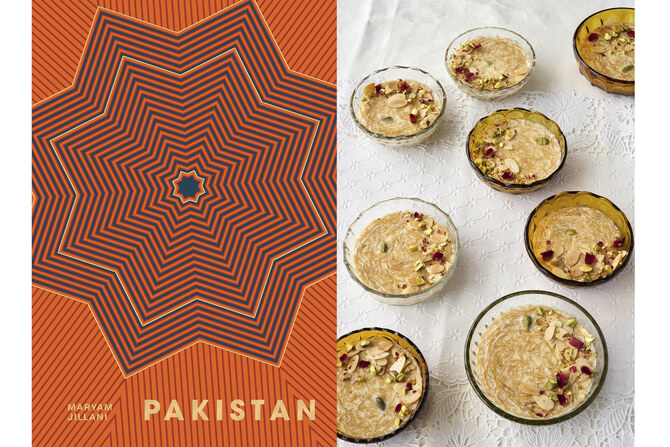

“But, of course, food,” said Jillani, a food writer and author of the new cookbook “Pakistan.” “Food is a big part of Eid.”

At the center of her grandmother Kulsoom’s table was always mutton pulao, a delicately spiced rice dish in which the broth that results from cooking bone-in meat is then used to cook the rice. Her uncle would make mutton karahi, diced meat simmered in tomato sauce spiked with ginger and chilies.

Cutlets, kebabs, lentil fritters and more rounded out the meal, while dollops of pungent garlic chutney and a cooling chutney with cilantro and mint cut through all the meat. For dessert were bowls of chopped fruit and seviyan, or semolina vermicelli noodles that are fried then simmered in cardamom-spiced milk.

The vegetable sides were the one thing that changed. Since Ramadan follows the lunar Islamic calendar, it can fall any time of year.

These dishes, and many of the associated memories, make it into Jillani’s book, but she would be the first to acknowledge they represent just a sliver of the nation’s varied cuisine.

Her father, who worked in international development, used to take the family to different parts of the country. Later, she did her own development fieldwork in education across rural Pakistan.

Along the way, she found striking differences between the tangier, punchier flavors in the east, toward India and China, and the milder but still flavorful cuisine in the west, toward Afghanistan.

“I knew our cuisine was a lot more than what we were finding on the Internet,” she said.

After moving to Washington, D.C. as a graduate student, she started the blog Pakistan Eats in 2008 to highlight dishes that were lesser known to Western cooks. Research on the book began 15 years later, and she visited 40 kitchens in homes across Pakistan.

“Even though I hadn’t lived in Pakistan for over 10 years, each kitchen felt like home,” she writes in the book’s introduction.

She includes what she calls “superstars” of the cuisine, such as chicken karahi, one of the first dishes Pakistanis learn to make when overseas to get a taste of home. The meat is seared in a karahi (skillet) and then braised in a tomato sauce spiced with cumin, coriander, ginger, garlic and chilies before a dollop of yogurt is stirred into the pot.

Other recipes reflect the diverse nature of Pakistan’s migrant communities, such as kabuli pulao, an Afghan rice dish made with beef, garam masala, chilies, sweetened carrots and raisins.

“The idea behind the cookbook is to try to play my small part in carving out a space for Pakistani food on the global culinary table,” she said.

And of course, honoring her grandmother’s mutton pulao.

Jillani is hosting Eid this year at her home, now in Manila, Philippines, and she plans to make it, as well as an Afghan-style eggplant, shami kebabs, and the cilantro and mint chutney.

“If I’m feeling especially ambitious that day, I might make a second mutton dish,” she said. “I’ve been a bit homesick.”

As Ramadan ends, a new cookbook sheds light on Pakistan’s varied cuisine

https://arab.news/62re6

As Ramadan ends, a new cookbook sheds light on Pakistan’s varied cuisine

- Cutlets, kebabs, mutton karahi, diced meat simmered in tomato sauce spiked with ginger and chilies, and more round out the meal on the Eid Al-Fitr holiday that marks the end of Ramadan

- These dishes, and many of the associated ones, make it into Maryam Jillani’s book, but she would be the first to acknowledge they represent just a sliver of the nation’s varied cuisine

Recipes for Success: Chef Jolbi Huacho offers advice and an avocado Nikkei recipe

DUBAI: Jolbi Huacho started his culinary career in Peru at the age of 22. He has since worked in several countries and now heads up two kitchens — Clay and Sushiyaki — in Dubai.

“My earliest food memories are connected to traditional stews made with ají peppers. I grew up surrounded by different preparations where ají was the starting point, and I clearly remember how the aromas coming from the kitchen sparked my curiosity from a young age,” Huacho tells Arab News. “Those dishes were part of my childhood and shaped my first connection with cooking.

“During my time at culinary school, I didn’t just learn techniques, I truly fell in love with the profession. By the time I finished my studies, I understood that this would not just be my career, but the path I wanted to fully commit to for the rest of my life.”

When you started out, what was the most common mistake you made?

Trying to execute dishes without fully understanding their origin and the reasoning behind each process. Cooking is a step-by-step evolution, you first need to understand where a dish comes from — the product, its technique and logic — before putting it into practice. Combining studying with constant hands-on practice helped me build a strong foundation and grow as a chef.

What’s your top tip for amateur chefs?

My main advice is to connect with what they are about to cook. Using a recipe or a video as a reference helps to understand the process before putting it into practice. From there, it’s important to enjoy the experience, cook without pressure, and put care into what you prepare. Everyone can cook. Each person has their own style. And, in the end, cooking is about enjoying and sharing food. Cooking at home shouldn’t be stressful; taste as you go, adjust when needed, and have fun with it

What one ingredient can instantly improve any dish? (And why?)

More than a single ingredient, I believe what truly elevates any dish is a well-executed base. A properly made reduction — whether from a stock, jus, or sauce — adds depth, balance, and intensity of flavor. It’s not about adding more elements, but about using the right technique and respecting the process to bring out the best in a dish.

When you go out to eat, do you find yourself critiquing the food?

It’s not just about the food, but also the service, timing, atmosphere, and the overall feeling of the place.

What’s the most-common issue that you find in other restaurants?

When passion and professionalism doesn’t cross all areas. When every part of a restaurant is handled with care and commitment, the experience naturally comes together, regardless of the cuisine or concept.

What’s your favorite cuisine or dish to order?

I’m very drawn to fusion cooking and a wide range of flavors. I enjoy dishes like a good ramen or donburi for their depth and umami, as well as classics such as a well-made carbonara or a fresh ceviche. More than the cuisine itself, what matters most is proper execution and a strong sense of identity in the dish.

What’s your go-to dish if you have to cook something quickly at home?

I usually go for simple dishes such as a katsu sando, miso soup, gyozas, or even a ceviche. These are dishes that don’t take much time and deliver great flavor with minimal steps. It’s all about simplicity done well.

What customer behavior most annoys you?

As a chef — or just as a professional — you must be prepared for all kinds of situations. Issues and requests will always arise. What truly matters is not the problem itself, but how it is handled: being present, listening, and always focusing on finding a solution. When situations are managed with professionalism, it’s possible to reach an outcome where both the guest and the (staff) feel satisfied.

What’s your favorite dish to cook?

Ceviche. I enjoy it because of its freshness and the balance between acidity and umami. With just a few elements, you can achieve very intense flavors. Good quality fish, treated with care and cured at the right moment, combined with a well-made leche de tigre, says everything. It’s a simple dish, but it requires respect for the product, proper timing, and precision.

What’s the most difficult dish for you to get right?

Seemingly simple dishes can be very hard. Preparations where there is nowhere to hide mistakes, such as a proper ramen broth, a well-executed fried rice, or fish that is cured or cooked to the exact point. In these dishes, technique, timing, and respect for the product must be precise, because even the smallest mistake becomes immediately noticeable.

What are you like as a leader?

I consider myself balanced, but demanding. I strongly believe that without discipline, consistency, and high standards, there is no real growth. I enjoy bringing out the best in people, teaching — and also learning, because cooking is a constant evolution.

I am disciplined when it comes to standards, technique, and consistency. But, at the same time, I value respect and people’s development. I am direct and expressive, and I believe a chef must display character and leadership. But that doesn’t mean shouting. For me, a kitchen works best with discipline, consistency, clear communication, and strong leadership.

Chef Jolbi’s avocado Nikkei

The avocado Nikkei is a dish that brings together creaminess, acidity, smokiness, and umami in a single bite.

It is built around a rocoto chimichurri quickly stir-fried in very hot oil, delivering depth and intensity. This is combined with creamy avocado, a tiger milk rich in seafood and fish umami, and finished with a burnt tortilla oil that adds subtle smoky notes.

A bright, acidic chalacita balances the dish, resulting in a fresh, bold, and addictive preparation with clearly layered flavors.

Smoked Rocoto Chimichurri

(Rocoto, It’s a chili from Peru, but can be replaced with red Holland chili.

Avocado Nikkei

Ingredients:

• Rocoto (or red Holland chili), finely chopped – 100 g

• Red onion, brunoise – 100 g

• Garlic, finely chopped – 30 g

• Vegetable oil – 100 g

• Fresh coriander (cilantro), chopped – 30 g

• Fresh parsley, chopped – 30 g

• White vinegar – 20 g

• Sugar – 10 g

• Salt – 5 g

Preparation

Heat the vegetable oil in a pan over medium heat. Add the rocoto, red onion, and garlic, and sauté gently for about 5 minutes, until softened and aromatic, without browning. Remove the pan from the heat and allow the mixture to cool slightly. Once cooled, add the coriander, parsley, vinegar, sugar, and salt. Mix well until fully combined.

Let the chimichurri cool completely, then adjust seasoning if needed and set aside until ready to use.

Black Tortilla Oil

Ingredients

• Flour tortillas (wrap) – 600 g

• Vegetable oil – 180 g

• Salt – 5 g

Preparation

The flour tortillas are baked in the oven at 200–220°C until they are approximately 85–90% burnt, achieving a deep dark color without turning to ash. Once roasted, they are removed from the oven and slightly cooled, then blended together with the vegetable oil and salt at high speed until a smooth and well-emulsified oil is obtained. The mixture can be strained if a finer texture is desired, then transferred to a squeeze bottle or airtight container. Before use, the oil should be shaken well to re-emulsify the solids with the oil.

Tiger Milk

Ingredients

• White fish (fresh, skinless) – 50 g

• Lime juice – 200 g

• Fish stock (fumet) – 80 g

• Celery – 50 g

• Onion – 50 g

• Garlic – 20 g

• Ginger – 10 g

• Red Holland chili – 10 g

• Coriander (cilantro) – 20 g

• Salt – 5 g

Preparation

All vegetables are cut into mirepoix and placed in a bowl together with salt, then gently crushed using a mortar to release their juices and aromas, allowing them to rest for about five minutes. After resting, lime juice and fish stock are added to the vegetable mixture. Separately, the fish is lightly cured with a small amount of lime juice and salt. Once cured, the fish is added to the vegetable mixture, and everything is blended at full speed in short pulses three seconds at a time, repeated three times to avoid overheating and preserve freshness. The mixture is then strained, and the resulting liquid is adjusted for seasoning if needed. The tiger milk is ready to use.

Chalaquita

Ingredients

Red Holland chili, 50 g, fine brunoise

White onion, 50 g, fine brunoise

Coriander stems, 30 g, fine brunoise

Lime juice, 50 g

White vinegar, 10 g

Vegetable oil, 30 g

Salt, 4 g

White pepper, 2 g

Preparation

Finely dice all solid ingredients into a small brunoise. Place them in a bowl and add the lime juice, white vinegar, and vegetable oil. Season with salt and white pepper, mix well, and adjust seasoning if needed. Keep refrigerated until use.

Plating – Avocado Nikkei

In a bowl, place ½ avocado, 2 tablespoons of rocoto chimichurri, salt, and white pepper. Using a fork, gently mash and mix to achieve a rustic, creamy texture, leaving small avocado chunks (not a smooth purée). Adjust seasoning and set aside. Place this mixture in the center of the plate, forming the base, on top, place the remaining half of the avocado, keeping its natural shape.

Add a small amount of tiger milk in the center of the avocado and finish with a few drops of black tortilla oil. Top with fresh chalacita and finish with coriander cress, ensuring a clean, balanced, and elegant presentation.