ZAGREB: Croatia’s populist President Zoran Milanovic was re-elected in a landslide, defeating his conservative rival in Sunday’s run-off, official results showed.

Milanovic took more than 74 percent of the vote and Dragan Primorac, backed by the center-right HDZ party that governs Croatia, almost 26 percent, with nearly all the votes counted.

It was the highest score achieved by a presidential candidate since the former Yugoslav republic’s independence in 1991.

While the role of the president is largely ceremonial in Croatia, Milanovic’s wide victory is the latest setback for the HDZ and Prime Minister Andrej Plenkovic — Milanovic’s political arch-rival — after a high-profile corruption affair in November.

“Croatia, thank you!,” Milanovic told his supporters who gathered at a Zagreb art and music club to celebrate his success.

“I see this victory as a recognition of my work in the last five years and a plebiscite message from Croatian people to those who should hear it,” he said in a reference to the HDZ-led government.

The outspoken Milanovic, backed by the left-wing opposition, won more than 49 percent of the vote in the contest’s first round two weeks ago — narrowly missing an outright victory.

Turnout Sunday was nearly 44 percent, slightly lower than in the first round, the electoral commission said.

The vote was held as the European Union member nation of 3.8 million people struggles with the highest inflation rate in the eurozone, endemic corruption and a labor shortage.

Even with its limited roles, many Croatians see the presidency as key to providing a political balance by preventing one party from holding all the levers of power.

Croatia has been mainly governed by the HDZ since independence.

The party “has too much control and Plenkovic is transforming into an autocrat,” Mia, a 35-year-old administrator from Zagreb who declined to give her last name, told AFP explaining her support for the incumbent.

Milanovic, a former left-wing prime minister, won the presidency in 2020 with the backing of the main opposition Social Democrats (SDP) party.

A key figure in the country’s political scene for nearly two decades, he has increasingly employed offensive, populist rhetoric during frequent attacks aimed at EU and local officials.

“Milanovic is a sort of a political omnivore,” political analyst Zarko Puhovski told AFP, saying the president was largely seen as the “only, at least symbolic, counterbalance to the government and Plenkovic’s power.”

His no-holds-barred speaking style has sent Milanovic’s popularity soaring and helped attract the backing of right-wing supporters.

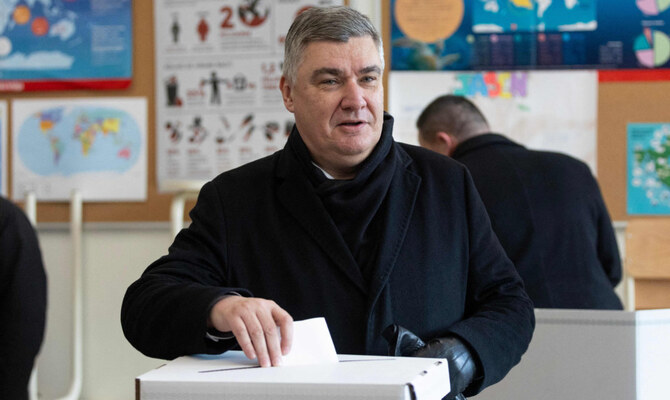

Earlier Sunday, after voting in Zagreb, Milanovic criticized Brussels as “in many ways autocratic and non-representative,” run by officials who are not elected.

The 58-year-old also regularly pans the HDZ over the party’s perennial problems with corruption, while also referring to Plenkovic as “Brussels’ clerk.”

Primorac, a former education and science minister returning to politics after a 15-year absence, has campaigned as a unifier for Croatia. The 59-year-old also insisted on patriotism and family values.

“With my program, I wanted to send a clear message that Croatia can and deserves better,” he told supporters on Sunday evening as the official results confirmed his crushing defeat.

But critics were saying Primorac lacked political charisma and failed to rally the HDZ base behind him.

He accused Milanovic of being a “pro-Russian puppet” who has undermined Croatia’s credibility in NATO and the European Union.

Milanovic condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine but has also criticized the West’s military support for Kyiv.

He is also a prominent opponent of a program that would have seen Croatian soldiers help train Ukrainian troops in Germany.

“The defense of democracy is not to tell everyone who doesn’t think like you that he’s a ‘Russian player’,” Milanovic told reporters on Sunday.

Such a communication style is “in fact totalitarian,” he added.

Meanwhile, young Croatians voiced frustration over lack of discussion among political leaders over the issues that interest them, such as housing or students’ standard of living.

“We hear them (politicians) talking mostly about old, recycled issues. What’s important to young people doesn’t even cross their minds,” student Ivana Vuckovic, 20, told AFP.