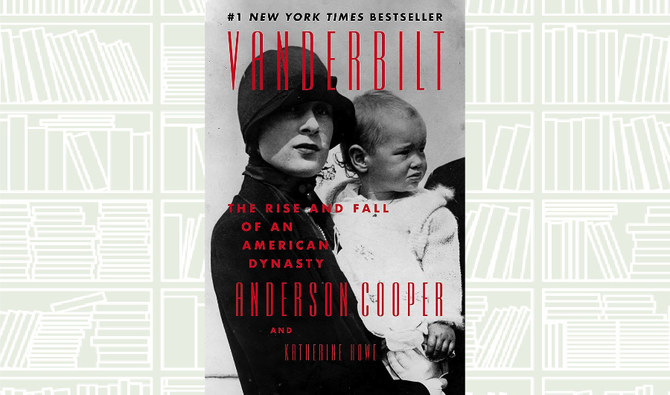

Written during the pandemic in 2021, “Vanderbilt: The Rise and Fall of an American Dynasty” looks at the Vanderbilt family, one of the most famous in US history, written by one of its own.

It was penned by journalist Anderson Cooper, formerly of CNN, and while many of us rifled through old archives while on lockdown in our own homes, Cooper attempted to piece together fragments of his own history — and US history.

The book begins with young Cornelius “the Commodore” Vanderbilt at the beginning of the 19th century. Through grit, and a pathological desire to acquire money at all costs, he was able to build two giant empires, one in shipping and another in railroads, that would make him the richest man in America. His staggering fortune was fought over by his heirs until well after his death in 1877.

His great-great-great-grandson is Cooper and this personal yet exhaustive book covers a vast amount of real estate — both in stories and locations — as historian Katherine Howe, his co-writer, and Cooper explore the story of the legendary family and its influence.

Cooper and Howe breathe life into the former’s ancestors who built the family’s vast empire, basked in the Commodore’s wealth and became synonymous with American capitalism and high society.

Moving from old Manhattan to the lavish Fifth Avenue, from the ornate summer palaces to the courts of Europe and modern-day New York, Cooper and Howe recount the triumphs and tragedies of this American dynasty.

The vignettes are often fascinating and give context to tales often recounted, like that of Alva Belmont, who was married to a Vanderbilt before pivoting to a world of activism. In her heyday she hosted one of the most lavish gala balls of all time, held in 1883, which inspired many a TV series and fanciful gossip following her rivalry with the infamous Caroline Schermerhorn Astor.

The story looks at the melancholic life of Alva’s daughter, Consuelo, and at her eventual happy ending.

Cooper and Howe delve into corners of stories that are more or less unknown. I was particularly fascinated by the story of his relative who lived in a museum for years, before being eventually kicked out.

The stories link and go back and forth on the timeline, perhaps making it slightly confusing for the lay reader.

It does really require the reader to have some prior knowledge of the Vanderbilt family, with its many scandals and nuances.

The authors also go into detail about the lives, and deaths, of the many Vanderbilt men.

The last part of the book spends time exploring the late Gloria Vanderbilt, Cooper’s mother. These passages are the most emotional in the book.

Cooper, who is now a father, explains how writing the book helped to provide a historical context which his son can read about in later life to understand the story behind the stories, and tall tales, written about their family.