DHAHRAN: Saudi filmmakers of the future were given a masterclass in the latest animation techniques as part of the Saudi Film Festival this week.

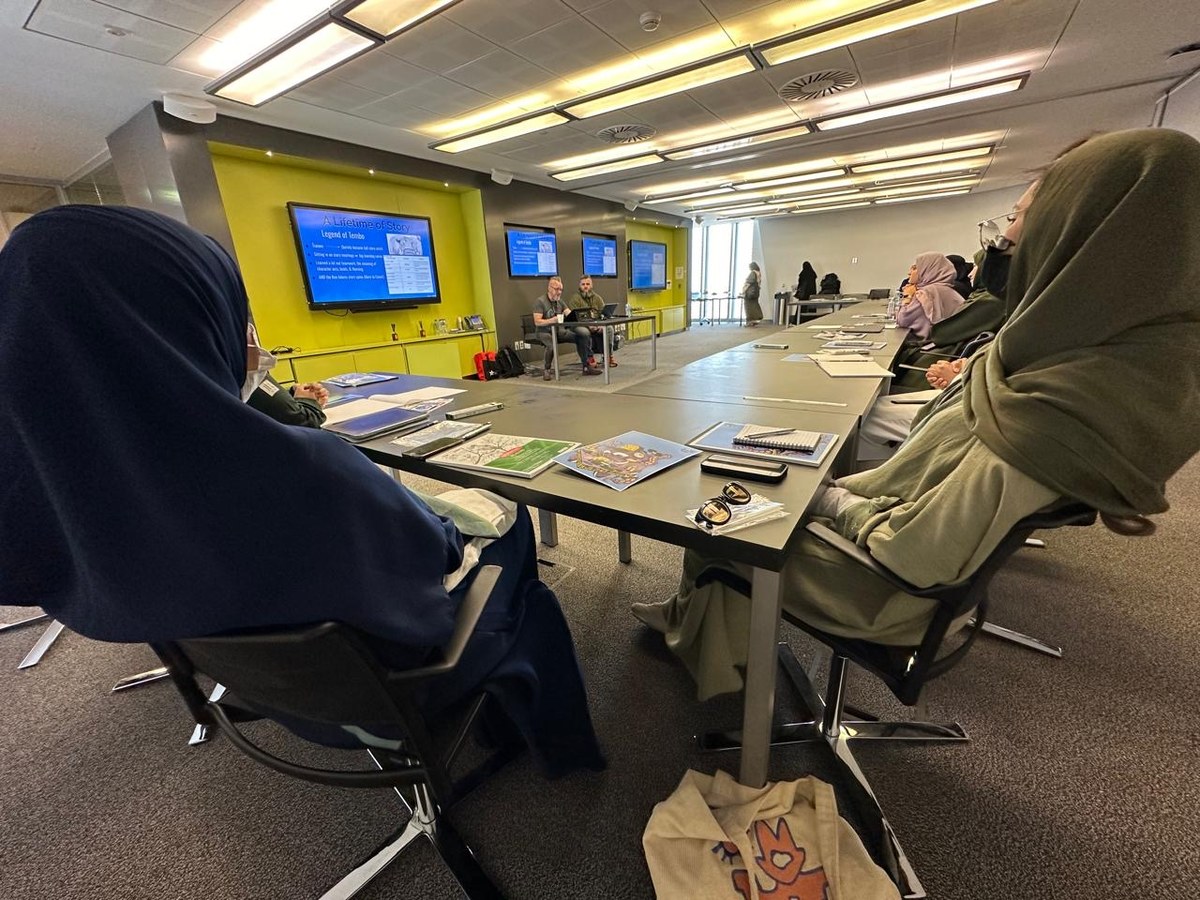

The animation workshops were led by experts from the US as part of a collaboration between the festival and the American Chamber of Commerce and US Consulate in Dhahran.

The animation workshops were led by experts from the US as part of a collaboration between the festival and the American Chamber of Commerce and US Consulate in Dhahran. (Supplied)

Todd Albert Nims, one of the pioneers in shaping the Saudi film industry over the past decade, told Arab News that with a population of 36 million, many under 35, Saudi Arabia is ripe with potential in the film sector.

Nims, an American who was born and raised in Dhahran, is now head of the AmCham Arts, Culture and Entertainment Committee, and has been involved in all aspects of Saudi-centered films, from acting to producing.

“I went to the first Saudi Film Festival in 2008 and worked with them on bringing the Saudi Film Festival into Ithra … I was there with them, and I’ve been here within this journey for the last 16 years,” he said.

Nims said that many Saudis grew up watching Disney films, and began their filmmaking efforts creating short content on YouTube.

He said there is huge potential for the Saudi market to grow, adding that he wanted to offer young filmmakers the opportunity to “gain expertise right in their backyard.”

Travis Blaise, who has over three decades of experience in animation, and has worked on Disney classics such as “Beauty and the Beast” and “The Lion King,” was on hand to conduct a five-day workshop.

“I was brought on to bring something new and unique to this Saudi Film Festival, which was bringing storytelling, or visual storytelling, to script,” he told Arab News.

Together with fellow American William Winkler, Blaise dedicated each day to bringing the overall picture to life, sketching ideas, developing the story structure, and even discuss the backstory of characters.

The goal was for each student to develop their own 30-second script. The workshop began with 11 students, but the figure soon ballooned to 20.

“Every single student was Saudi; most of them were women from several universities, while a couple were already professionals working in the industry,” Blaise said.

“I love the excitement and passion that they (the Saudi students) share because I have shared that same passion for the last 34 years, and the fact that I can bring something of my own experience to someone who is passionate and open-minded and willing to learn about film really is exciting,” he said.

The experts told Arab News that they are committed to building connections between the US and Saudi film industries, recognizing its potential to inspire, educate, and entertain audiences both domestically and internationally.

“Through filmmaking, we aim to strengthen ties between the US and Saudi Arabia by fostering mutual understanding and creative collaboration,” Alison Dilworth, the US deputy chief of mission, told Arab News.