CAIRO: Jordanian Foreign Minister Ayman Safadi said on Saturday that “famine” in Gaza can be dealt with in a short time if Israel opened the land crossings for aid to enter.

Safadi made the comments at a press conference with his Egyptian and French counterparts in Cairo.

The UN and partners have warned that famine could occur in devastated, largely isolated northern Gaza as early as this month

A three-ship convoy left a port in Cyprus on Saturday with 400 tonnes of food and other supplies for Gaza as concerns about hunger in the territory soar.

World Central Kitchen said the vessels and a barge were carrying ready-to-eat items like rice, pasta, flour, legumes, canned vegetables, and proteins, enough to prepare more than 1 million meals. Also on board were dates, traditionally eaten to break the daily fast during the holy month of Ramadan.

It was not clear when the ships would reach Gaza.

BACKGROUND

An Open Arms ship inaugurated the direct sea route to the Palestinian territory earlier this month, carrying 200 tonnes of food, water, and other aid.

An Open Arms ship inaugurated the direct sea route to the Palestinian territory earlier this month, carrying 200 tonnes of food, water, and other aid.

Humanitarian officials say deliveries by sea and air are not enough and that Israel must allow far more aid by road. The top UN court has ordered Israel to open more land crossings and take other measures to address the humanitarian crisis.

The US has welcomed the formation of a new Palestinian autonomous government, signaling that it would accept the revised Cabinet lineup as a step toward political reform.

The administration of President Joe Biden has called for “revitalizing” the West Bank-based Palestinian Authority in the hope that it can also administer the Gaza Strip once the Israel-Hamas war ends.

It is headed by Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas, who tapped US-educated economist Mohammed Mustafa as prime minister earlier this month.

But both Israel and Hamas — which drove Abbas’ security forces from Gaza in a 2007 takeover — reject the idea of it administering Gaza, and Hamas rejects the formation of the new Palestinian government as illegitimate.

The authority also has little popular support or legitimacy among Palestinians because of its security cooperation with Israel in the West Bank.

The war began after Hamas-led militants stormed across southern Israel on Oct. 7, killing 1,200 people, mostly civilians, and taking about 250 others hostage.

More than 400 Palestinians have been killed by Israeli forces or settlers in the West Bank or east Jerusalem since Oct. 7, according to local health authorities.

Dr. Fawaz Hamad, director of Al-Razi Hospital in Jenin, told local station Awda TV that Israeli forces killed a 13-year-old boy in nearby Qabatiya early Saturday. Israel’s military said the incident was under review.

A major challenge for anyone administering Gaza will be reconstruction. Nearly six months of war has destroyed critical infrastructure, including hospitals, schools, and homes, as well as roads, sewage systems, and the electrical grid.

Airstrikes and Israel’s ground offensive have left 32,705 Palestinians dead, local health authorities said on Saturday, with 82 bodies taken to hospitals in the past 24 hours. Gaza’s Health Ministry doesn’t distinguish between civilians and combatants in its toll but has said the majority of those killed have been women and children.

Israel says over one-third of the dead are militants.

However, it has not provided evidence to support that, and it blames Hamas for civilian casualties because the group operates in residential areas.

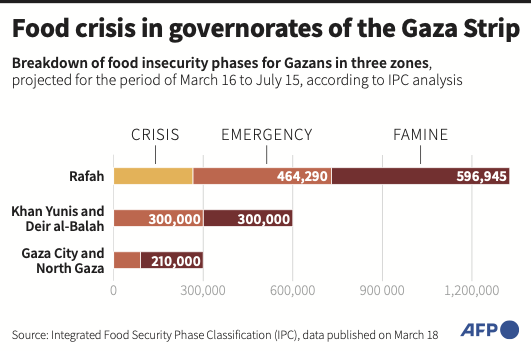

The fighting has displaced over 80 percent of Gaza’s population and pushed hundreds of thousands to the brink of famine, the UN and international aid agencies say. Israel’s military said it continued to strike dozens of targets in Gaza, days after the UN Security Council issued its first demand for a ceasefire.

Aid also fell on Gaza. During an airdrop on Friday, the US military said it had released over 100,000 pounds of aid that day and almost a million pounds overall, part of a multi-country effort.

Israel has said that after the war, it will maintain open-ended security control over Gaza and partner with Palestinians who are not affiliated with the Palestinian Authority or Hamas. Who in Gaza would be willing to take on such a role is unclear.

Hamas has warned Palestinians in Gaza against cooperating with Israel to administer the territory, saying anyone who does will be treated as a collaborator, which is understood as a death threat.

Hamas calls instead for all Palestinian factions to form a power-sharing government ahead of national elections, which have not taken place in 18 years.