WASHINGTON: There definitely were no muppets during the Permian Period, but there was a Kermit — or at least a forerunner of modern amphibians that has been named after the celebrity frog.

Scientists on Thursday described the fossilized skull of a creature called Kermitops gratus that lived in what is now Texas about 270 million years ago. It belongs to a lineage believed to have given rise to the three living branches of amphibians — frogs, salamanders and limbless caecilians.

While only the skull — measuring around 1.2 inches (3 cm) long — was discovered, the researchers think Kermitops had a stoutly built salamander-like body roughly 6-7 inches (15-18 cm) long, though salamanders would not evolve for another roughly 100 million years.

Amphibians are one of the four groups of living terrestrial vertebrates, along with reptiles, birds and mammals. The unique features of the Kermitops skull — a blend of archaic and more advanced features — are providing insight into amphibian evolution.

“Kermitops helps us understand the early history of amphibians by revealing there isn’t a clear trend of step by step becoming more like the modern amphibian,” said Calvin So, a George Washington University paleontology doctoral student and lead author of the study published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.

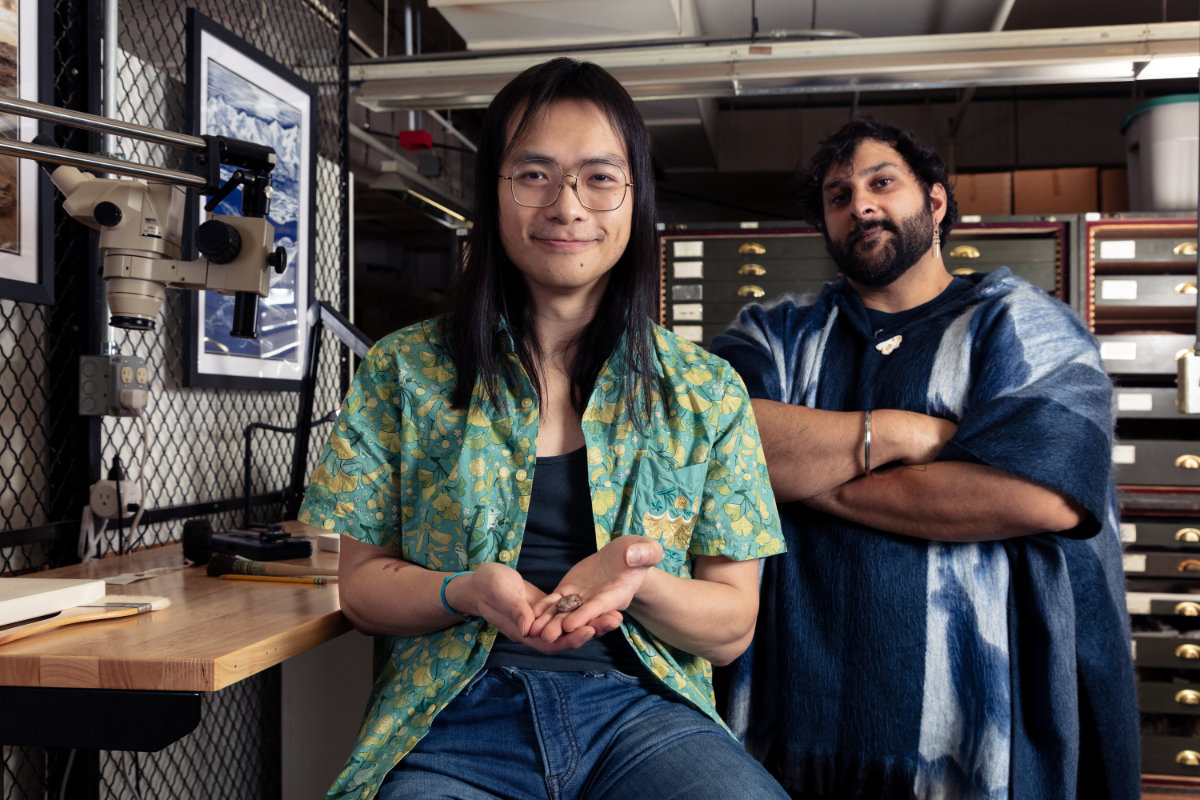

Calvin So (L), a doctoral student at George Washington University, and Arjan Mann, a Smithsonian postdoctoral paleontologist, pose with the fossil skull of the Permian period proto-amphibian Kermitops in the Smithsonianâ's National Museum of Natural History fossil collection, in Washington, D.C., in this undated handout picture. (Phillip R. Lee./Handout via REUTERS)

The fossil was collected in 1984 near Lake Kemp in Texas and kept in the expansive collection of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, but was not thoroughly studied until recently.

Kermitops had a rounded snout, not unlike frogs and salamanders. Preserved in its eye sockets were palpebral bones — or eyelid bones — a feature absent in today’s amphibians. Its skull is constructed of roof-like bones, in contrast to the thin and strut-like bones of modern amphibians.

“The length of the skull in front of the eyes is longer than the length of the skull behind the eyes, which differs from the other fossil amphibians living at the same time. We think this might have allowed Kermitops to snap its jaws closed faster, enabling capture of fast insect prey,” So said.

The fossil record of early amphibians and their forerunners is spotty, making it difficult to figure out the origins of modern amphibians.

“Kermitops, with its unique anatomy, really exemplifies the importance of continuing to add new fossil data to understanding this evolutionary problem,” said National Museum of Natural History paleontologist and study co-author Arjan Mann.

Kermit the Frog was created by the late American puppeteer Jim Henson in 1955, and a Kermit puppet made in the 1970s is in the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History as an important cultural object.

Kermitops means “Kermit face,” a nod to the muppet’s humorous look.

“We thought that the eyelid bones gave the fossil a bug-eyed look, and combined with a lopsided smile produced by slight crushing during the preservation of the fossil, we really thought it looked like Kermit the Frog,” So said.

Kermitops belonged to a group called temnospondyls that arose a few tens of millions of years after the first land vertebrates evolved from fish ancestors. The biggest temnospondyls superficially resembled crocodiles, including two that each were around 20 feet (6 meters) in length, Prionosuchus and Mastodonsaurus.

Temnospondyls are considered the progenitor lineage of modern amphibians, Mann said.

Kermitops existed about 20 million years before the worst mass extinction in Earth’s history and about 40 million years before the first dinosaurs. It lived alongside other members of the amphibian lineage as well as the impressive sail-backed Dimetrodon, a predator related to the mammalian lineage.

The environment in which Kermitops lived appears to have alternated between warm and humid seasons and hot and arid seasons.

“This environment would be similar to modern-day monsoons that take place in the Southwest US and Southeast Asia,” So said.