PARIS: In 2023, the world’s oceans took up an enormous amount of excess heat, enough to “boil away billions of Olympic-sized swimming pools,” according to an annual report published Thursday.

Oceans cover 70 percent of the planet and have kept the Earth’s surface livable by absorbing 90 percent of the excess heat produced by the carbon pollution from human activity since the dawn of the industrial age.

In 2023, the oceans soaked up around 9 to 15 zettajoules more than in 2022, according to the respective estimates from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Chinese Institute of Atmospheric Physics (IAP).

One zettajoule of energy is roughly equivalent to ten times the electricity generated worldwide in a year.

“Annually the entire globe consumes around half a zettajoule of energy to fuel our economies,” according to statement.

“Another way to think about this is 15 zettajoules is enough energy to boil away 2.3 billion Olympic-sized swimming pools.”

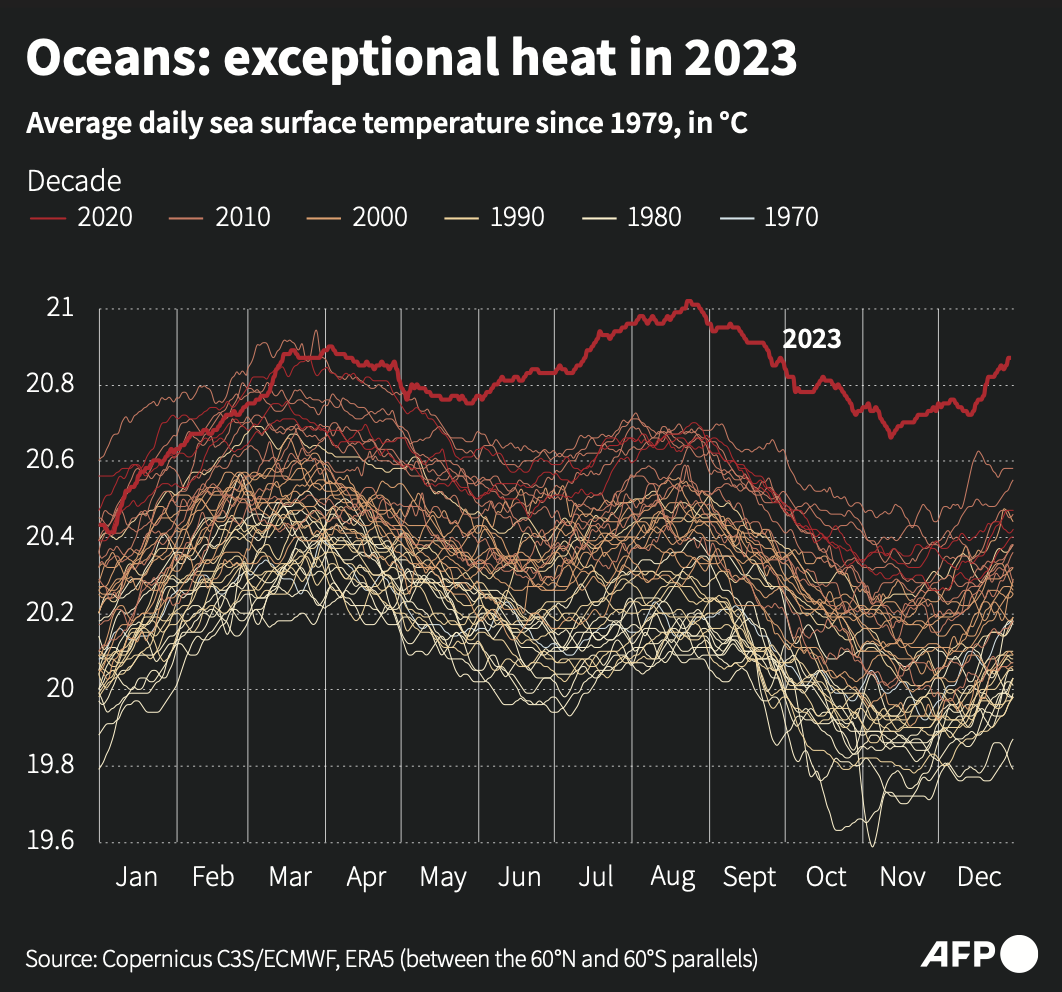

In 2023, sea surface temperature and the energy stored in the upper 2000 meters of the ocean both reached record highs, according to the study published in the journal Advances in Atmospheric Sciences.

The amount of energy stored in the oceans is a key indicator of global warming because it is less affected by natural climate variability than sea surface temperature.

Some of the colossal amounts of energy stored in the ocean helped make 2023, a year rife with heatwaves, droughts and wildfires, the hottest on record.

That’s because the warmer the oceans gets, the more heat and moisture enters the atmosphere. This leads to increasingly erratic weather, like fierce winds and powerful rain.

Warmer sea surface temperatures are driven mostly by global warming, caused mainly by the burning of fossil fuels.

Every few years, a naturally occurring weather phenomenon, El Nino, warms the sea surface in the southern Pacific, leading to hotter weather globally. The current El Nino is expected to peak in 2024.

Conversely, a mirror phenomenon called La Nina periodically helps cool the surface of the ocean.

Increasing water temperatures and ocean salinity — also at an all-time high — directly contribute to a process of “stratification,” where water separates into layers that no longer mix.

This has wide-ranging implications because it affects the exchange of heat, oxygen and carbon between the ocean and atmosphere, with effects including a loss of oxygen in the ocean.

Scientists are also concerned about the long-term capacity of the oceans to continue absorbing 90 percent of the excess heat from human activity.