Fears of ethnic cleansing and repression will force more than 120,000 ethnic Armenians to flee Nagorno-Karabakh and head to Armenia, the leadership of the breakaway region said on Sunday.

“Our people do not want to live as part of Azerbaijan,” said David Babayan, an adviser to Samvel Shahramanyan, president of the self-styled Republic of Artsakh. He added that “99.9 percent prefer to leave our historic lands.”

Babayan’s remarks came as Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan said the Karabakh Armenians were likely to leave the region, and that Armenia was ready to take them in following defeat last week at the hands of Azerbaijan.

“The fate of our poor people will go down in history as a disgrace, and a shame for the Armenian people and for the whole civilized world,” Babayan said. “Those responsible for our fate will one day have to answer for their sins.”

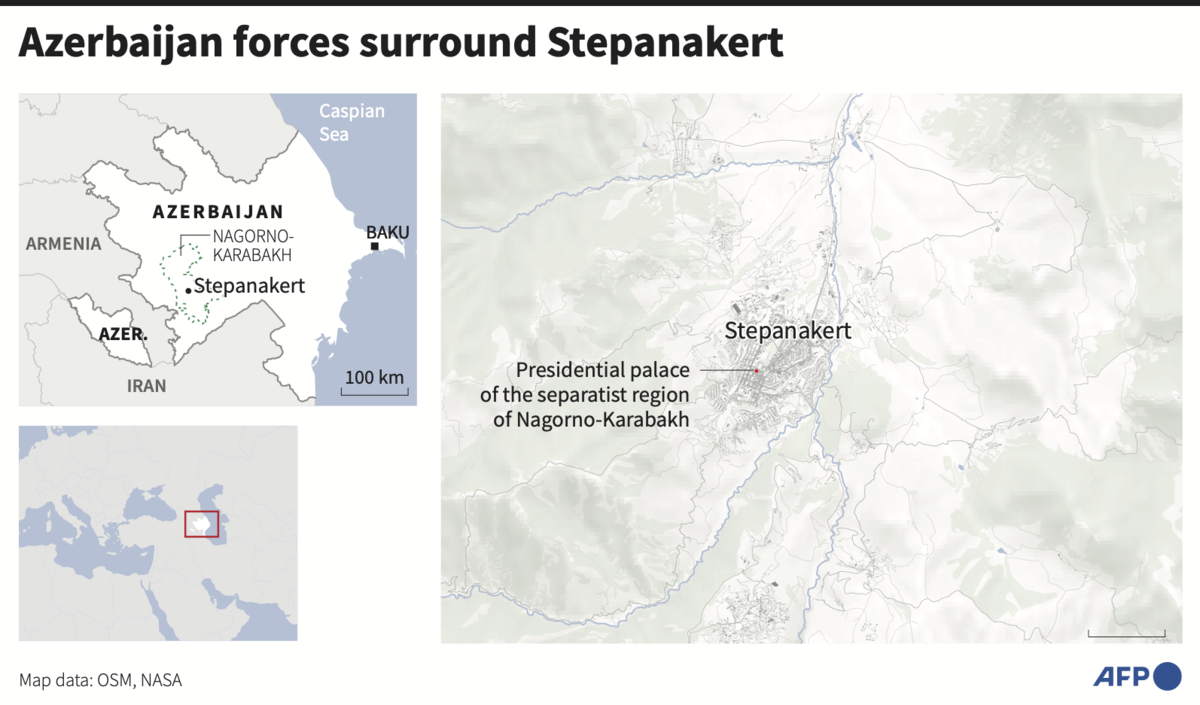

The Armenians of Karabakh — a territory internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan, but previously beyond Baku’s control — were forced to declare a ceasefire on Sept. 20 after a lightning 24-hour military operation by the much larger Azerbaijani military.

Azerbaijan said it will guarantee their rights and integrate the region, but the Armenians say they fear repression.

BACKGROUND

This week’s lightning operation could mark a historic geopolitical shift, with Azerbaijan victorious over the separatists and Armenia publicly distancing itself from its traditional ally Russia.

Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan said that his former Soviet republic’s current foreign security alliances were ‘ineffective’ and ‘insufficient.’

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov has accused Armenia of ‘adding fuel to the fire’ with its public rhetoric.

Hundreds of refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh have begun arriving in Armenia, local officials said.

The Armenian leaders of Karabakh said in a statement that all those made homeless by the Azerbaijani military operation and wanting to leave will be escorted to Armenia by Russian peacekeepers.

READ MORE:

• Why Lebanese-Armenians feel the pull of the Nagorno-Karabakh war

Reporters near the village of Kornidzor on the Armenian border saw heavily laden cars pass into Armenia, with one of the drivers saying the vehicles were from Nagorno-Karabakh.

It was unclear when the bulk of the population will move down the Lachin corridor, which links the territory to Armenia.

Meanwhile, Armenia’s leader is facing calls to resign for failing to save Karabakh.

In an address to the nation on Sunday, Pashinyan said some humanitarian aid had arrived, but the Armenians of Karabakh still faced “the danger of ethnic cleansing.”

He added: “If proper conditions are not created for the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh to live in their homes and there are no effective protection mechanisms against ethnic cleansing, the likelihood is rising that the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh will see exile from their homeland as the only way to save their lives and identity.”

Pashinyan signaled a major foreign policy shift away from Russia, following Moscow’s refusal to enter the conflictHe said that the former Soviet republic’s current foreign security alliances were “ineffective” and “insufficient,” and added that Armenia could join the International Criminal Court.

Russian officials say Pashinyan is to blame for his own mishandling of the crisis, and have repeatedly said that Armenia, which borders Turkiye, Iran, Azerbaijan and Georgia, has few other friends in the region.

A humanitarian convoy for Nagorno-Karabakh moves along the Armenian side of the border near the town of Kornidzor. Tension was running high at the crossing on Sunday amid growing international concern. (AFP)

A mass exodus could change the delicate balance of power in the South Caucasus region.

Armenian authorities said that about 150 tons of humanitarian aid from Russia and another 65 tons of flour shipped by the International Committee of the Red Cross had arrived in the region.

With 2,000 peacekeepers in the region, Russia said that under the terms of the ceasefire six armored vehicles, more than 800 small arms, anti-tank weapons and portable air defense systems, as well as 22,000 ammunition rounds, had been handed in by Saturday.