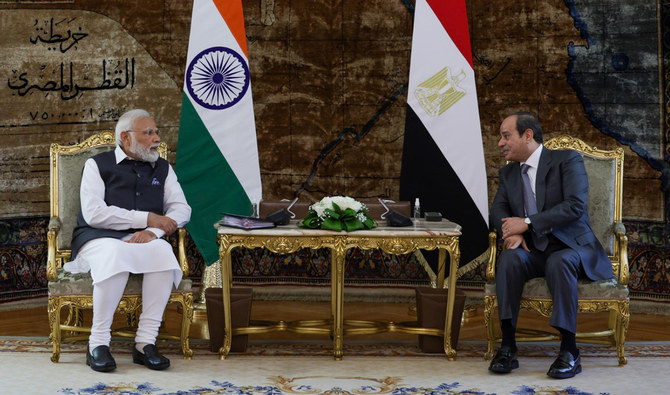

NEW DELHI: Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi signed on Sunday a strategic partnership agreement, underscoring growing ties between the two countries that experts say can spark geopolitical and economic significance.

Modi arrived in Cairo on Saturday afternoon following a four-day trip to the US, marking the first state visit to Egypt by an Indian premier since 1997.

He was awarded Egypt’s highest civilian honor, known as the Order of the Nile, during the trip that comes less than six months after El-Sisi’s visit to India earlier this year, when the leaders first announced plans to elevate their partnership.

“An agreement to elevate the bilateral relationship to a ‘Strategic Partnership’ was signed by the leaders,” Arindam Bagchi, spokesperson of India’s Ministry of External Affairs, said in a tweet on Sunday.

“The leaders discussed ways to further deepen the partnership between the two countries, including in trade & investment, defense & security, renewable energy, cultural and people to people ties.”

Bagchi said their meeting was “productive,” with India and Egypt also signing three other memoranda of understanding in agriculture, archaeology and antiquities, and competition law.

Modi also visited on Sunday the historic Al-Hakim Mosque in Cairo, recently renovated with the help of the India-based Dawoodi Bohra community, and met with Grand Mufti Shawki Allam, Egypt’s Islamic jurist.

In January, Modi and El-Sisi agreed to increase bilateral trade to $12 billion in the next five years, up from $7.3 billion in 2021-22.

The two countries signed several agreements in New Delhi then on expanding cooperation in cybersecurity, information technology, culture, and broadcasting.

Navdeep Suri, former Indian ambassador to Egypt, said India and Egypt had been drifting apart prior to this year’s engagements.

“After allowing the relationship to drift for years, it’s back on track,” Suri told Arab News.

According to Suri, India had built momentum by inviting El-Sisi as a chief guest on India’s Republic Day in January and had Egypt among special invitees for meetings of the Group of 20 biggest economies under Delhi’s presidency this year, which he said sends “a strong signal.”

Suri said: “There is now an opportunity to develop a special relationship with a country that, despite its present economic difficulties, will always be an important player in the Middle East.

“This kind of intensity and engagement have been missing for a long time.”

Closer ties with Egypt may also bring strategic benefits for India, experts say.

“Egypt’s pivotal position in the region is important for growing India’s profile in the region,” Dr. Zakir Hussain, a Middle East expert based in New Delhi, told Arab News.

“(India is) securing favorable treatment in trade, an industrial berth in the Suez Canal Free Zone, to access the Europe market and all those areas where Egypt has free trade deals such as Latin America, Africa, and the Middle East,” Hussain said, adding that “India needs to access these markets at preferential terms to achieve the target of $1 trillion merchandise exports by 2030.”

Modi’s visit to Cairo “holds great significance” in strengthening India-Egypt bilateral relations, said Mohammed Soliman, tech program director at the Middle East Institute in Washington DC.

With the countries discussing potential deals, such as the allocation of an economic zone for India in the Suez Canal area, they have the “potential to significantly impact the economic and strategic collaboration between the two nations,” he told Arab News.

“With India now surpassing the UK as the fifth-largest global economy, it sees Egypt as a potential launchpad for Indian manufacturing and defense industries,” Soliman said.

“Egypt’s strategic location, particularly with the Suez Canal, is central to Delhi’s global posture.”