LONDON: With at least 185 people killed during clashes between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces in recent days, the dreams of shift from military rule to civilian-led democracy have turned to dust, revealing that the transition plan was likely doomed from the start.

It is a far cry from the events of 2019, when the very forces now fighting one another worked together to oust the country’s autocratic ruler, Omar Al-Bashir. Analysts at that time described Sudan’s nascent transition to civilian-led democracy as a “glimmer of hope.”

“Most people are ignoring the ways in which the constitutional declaration of August 2019 set in place an unsustainable tension between the RSF and the Sudanese Armed Forces, both of which were recognized as official armed forces of Sudan,” Eric Reeves, an academic with more than 25 years of experience researching the country, told Arab News.

Combo image showing Sudan's army chief Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan (left) greeting a crowd in Khartoum's twin city of Omdurman on June 29, 2019 and RSF chief Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo greeting his supporters in Aprag village outside of Khartoum on June 22, 2019. (AFP & Reuters)

Now at loggerheads, Gen. Fattah Al-Burhan, head of the Armed Forces, leads the country’s transitional governing Sovereign Council, while his former deputy, Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, commonly known as Hemedti, leads the RSF.

“The problem with this is you can’t have two armies and two competing generals in one desperate country and expect this (peaceful transition), especially with so many unhappy civilians who experienced catastrophic decline in the economy, who are suffering from a great deal of malnutrition and unemployment, and the list goes on,” said Reeves.

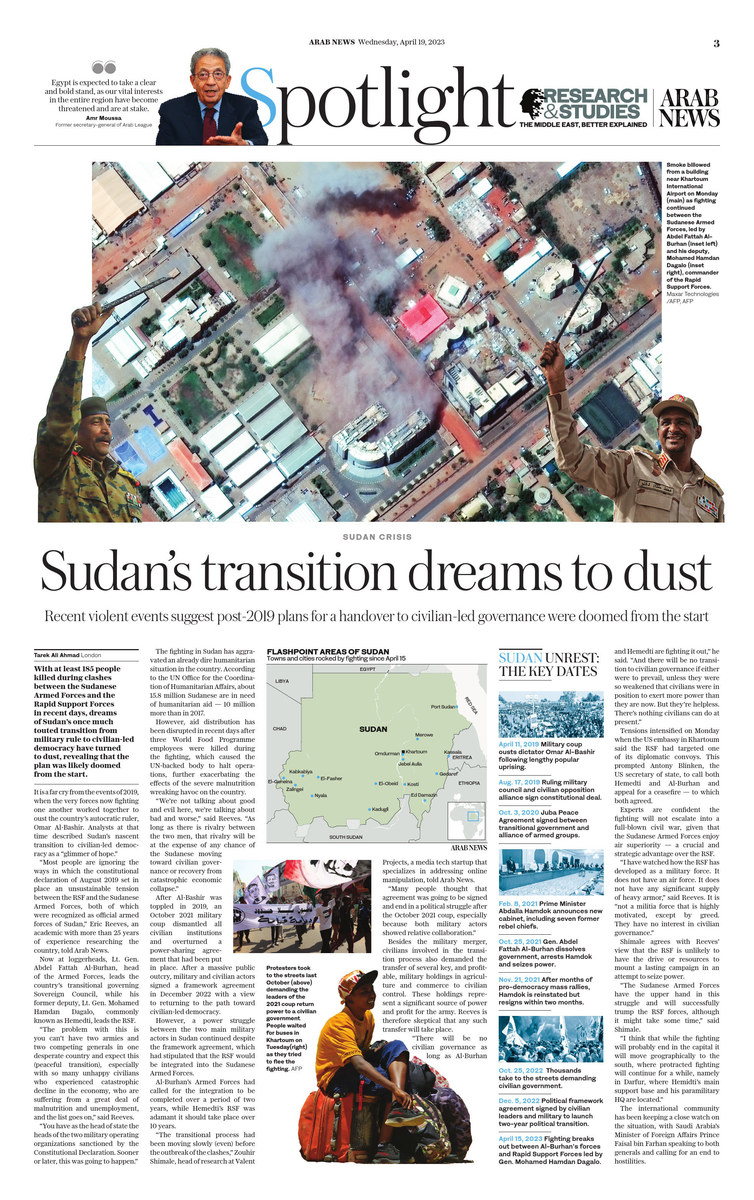

SUDAN UNREST:The Key Dates

April 11, 2019 Military coup ousts dictator Omar Al-Bashir following lengthy popular uprising.

Aug. 17, 2019 Ruling military council and civilian opposition alliance sign constitutional deal.

Oct. 3, 2020 Juba Peace Agreement signed between transitional government and alliance of armed groups.

Feb. 8, 2021 Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok announces new cabinet, including seven former rebel chiefs.

Oct. 25, 2021 Gen. Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan dissolves government, arrests Hamdok and seizes power.

Nov. 21, 2021 After months of pro-democracy mass rallies, Hamdok is reinstated but resigns within two months.

Oct. 25, 2022; Thousands take to the streets demanding civilian government.

Dec. 5, 2022 Political framework agreement signed by civilian leaders and military to launch two-year political transition.

April 15, 2023 Fighting breaks out between Al-Burhan’s forces and Rapid Support Forces led by Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo.

“You have as the head of state the heads of the two military operating organizations sanctioned by the Constitutional Declaration. Sooner or later, this was going to happen.”

The fighting in Sudan has aggravated an already dire humanitarian situation in the country. According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, about 15.8 million Sudanese are in need of humanitarian aid — 10 million more than in 2017.

People queue for bread outside a bakery amidst a food crisis in the south of Khartoum on April 17, 2023 as fighting in the Sudanese capital rages for a third day. (AFP)

However, aid distribution has been disrupted in recent days after three World Food Programme employees were killed during the fighting, which caused the UN-backed body to halt operations, further exacerbating the effects of the severe malnutrition wreaking havoc on the country.

“We’re not talking about good and evil here, we’re talking about bad and worse,” said Reeves. “As long as there is rivalry between the two men, that rivalry will be at the expense of any chance of the Sudanese moving toward civilian governance or recovery from catastrophic economic collapse.”

After Al-Bashir was toppled in 2019, an October 2021 military coup dismantled all civilian institutions and overturned a power-sharing agreement that had been put in place. After a massive public outcry, military and civilian actors signed a framework agreement in December 2022 with a view to returning to the path toward civilian-led democracy.

However, a power struggle between the two main military actors in Sudan continued despite the framework agreement, which had stipulated that the RSF would be integrated into the Sudanese Armed Forces.

Al-Burhan’s Armed Forces had called for the integration to be completed over a period of two years, while Hemedti’s RSF was adamant it should take place over 10 years.

“The transitional process had been moving slowly (even) before the outbreak of the clashes,” Zouhir Shimale, head of research at Valent Projects, a media tech startup that specializes in addressing online manipulation, told Arab News.

“Many people thought that agreement was going to be signed and end in a political struggle after the October 2021 coup, especially because both military actors showed relative collaboration.”

Protesters took to the streets in Khartoum last October, demanding the leaders of the 2021 coup return power to a civilian government. (AFP file)

Besides the military merger, civilians involved in the transition process also demanded the transfer of several key, and profitable, military holdings in agriculture and commerce to civilian control. These holdings represent a significant source of power and profit for the army. Reeves is therefore skeptical that any such transfer will take place.

“There will be no civilian governance as long as Al-Burhan and Hemedti are fighting it out,” he said. “And there will be no transition to civilian governance if either were to prevail, unless they were so weakened that civilians were in position to exert more power than they are now. But they’re helpless. There’s nothing civilians can do at present.”

Tensions intensified on Monday when the US embassy in Khartoum said the RSF had targeted one of its diplomatic convoys. This prompted Antony Blinken, the US secretary of state, to call both Hemedti and Al-Burhan and appeal for a ceasefire — to which both agreed.

Civilians greet army soldiers loyal to army chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan in the Red Sea city of Port Sudan on April 16, 2023. (AFP)

Experts are confident the fighting will not escalate into a full-blown civil war, given that the Sudanese Armed Forces enjoy air superiority — a crucial and strategic advantage over the RSF.

“I have watched how the RSF has developed as a military force. It does not have an air force. It does not have any significant supply of heavy armor,” said Reeves. It is “not a militia force that is highly motivated, except by greed. They have no interest in civilian governance.”

Opinion

This section contains relevant reference points, placed in (Opinion field)

Shimale agrees with Reeves’ view that the RSF is unlikely to have the drive or resources to mount a lasting campaign in an attempt to seize power.

“The Sudanese Armed Forces have the upper hand in this struggle and will successfully trump the RSF forces, although it might take some time,” said Shimale.

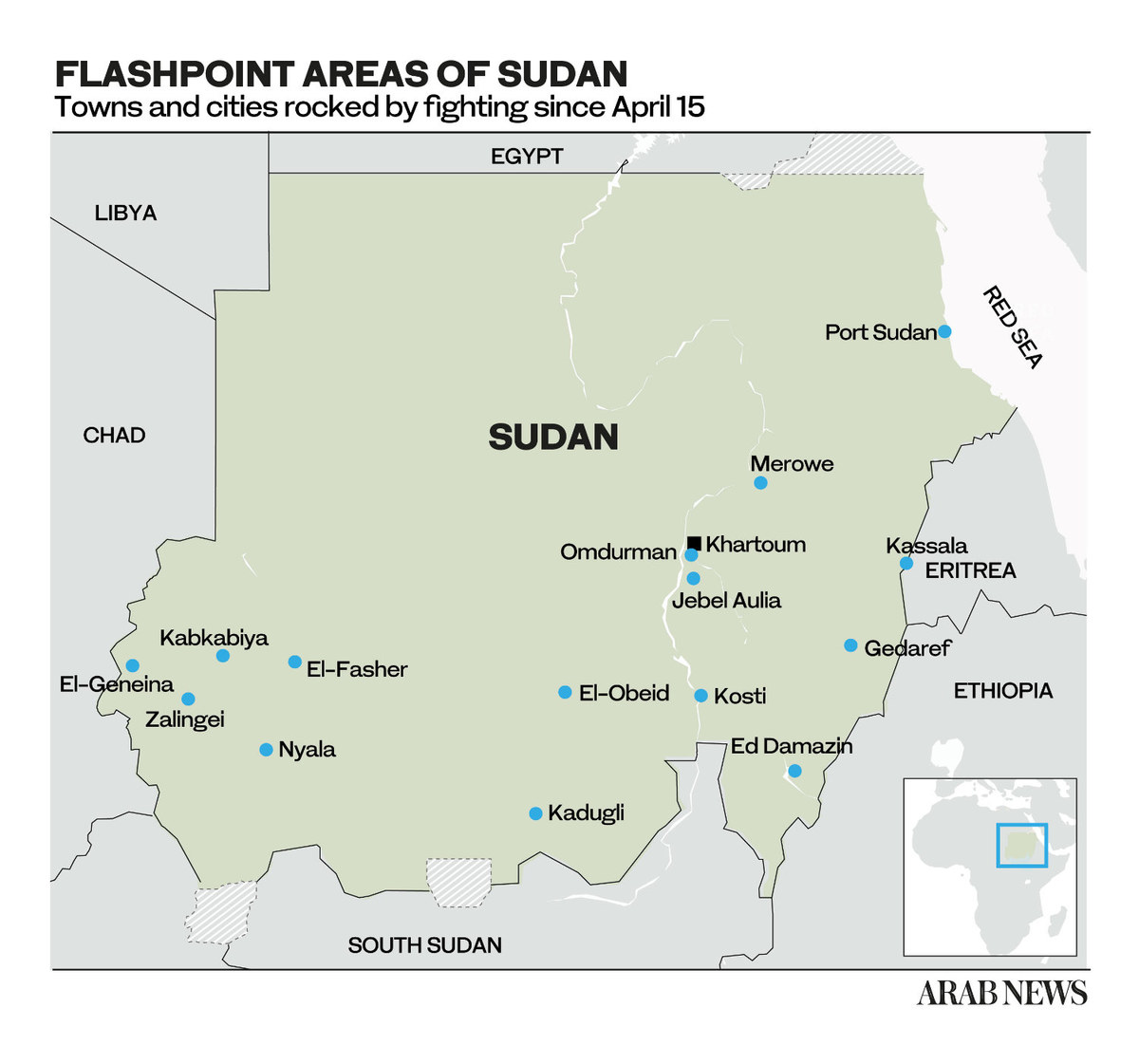

“I think that while the fighting will probably end in the capital it will move geographically to the south, where protracted fighting will continue for a while, namely in Darfur, where Hemidti’s main support base and his paramilitary HQ are located.”

The international community has been keeping a close watch on the situation, with Saudi Arabia’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Prince Faisal bin Farhan speaking to both generals and calling for an end to hostilities.