DUBAI: Even 22 years on from her untimely passing, few stars in the history of Arab cinema captivate the cultural imagination quite like Soad Hosny. The singer and actress known as “The Cinderella of Egyptian cinema” was a key part of the rise of her country’s movie culture, starring in a number of the most popular Arab films of the Sixties and Seventies, working with greats including Omar Sharif and director Youssef Chahine.

But Hosny’s enduring popularity is due to something more than just her talent. As brilliant as she was an artist, it was her bewitching personality — both familiar and always out of reach — that even those who knew her are still attempting to figure out to this day.

Soad Hosny with Hussein Fahmy in 1972’s ‘Watch Out for ZouZou.’ (Supplied)

“It was like she was split into two different personalities, and you could always see both on her face” famed Egyptian designer Karim Mekhtigian — who knew Hosny from his early childhood, being the nephew of her close friend and frequent collaborator, producer Takfour Antonian — tells Arab News.

“Either in life or in film, Soad’s face could convey opposing feelings simultaneously. It was genuinely remarkable. One eye (could be) full of sadness, the other radiating happiness. She was never one thing. That’s part of what made her talent so remarkable,” he continues.

For Hosny herself, the fact that she took such varying roles over the decades in which she dominated Egyptian cinema while also topping its music charts was simply because she could not force herself to stay in any one mode for too long, growing restless if she felt stagnant creatively.

“By nature, I am bored,” Hosny said in an Egyptian television interview in 1984. “I do not wish to repeat the same thing. I can make political films; I can make entertaining films. Every film will present something new. I can play the naughty girl or the innocent wife. I am always looking to play different personalities. Each character I play has an atmosphere I can present. I want to play women in all their many facets.”

Soad Hosny holding Karim Mekhatagian as a baby. (Courtesy of Karim Mekhatagian)

Like many of her contemporaries, part of what made Hosny so suited to the career she chose was the fact that she grew up in an intensely artistic household, led by her father, the famed Islamic calligrapher Mohammad Hosny — a Kurdish artist who had settled in Egypt at the age of 19.

Young Soad, the daughter of her father’s second wife, grew up among 16 siblings and half-siblings, with numerous luminaries of the Arab world’s artistic community shuffling in and out of their home. Each of the children were affected by those interactions in different ways. Her sister Nagat, for example, also became an actress and singer, while her half-brother Ezz composed music for decades. Others played instruments or pursued fine arts, but none reached the heights of their sister Soad.

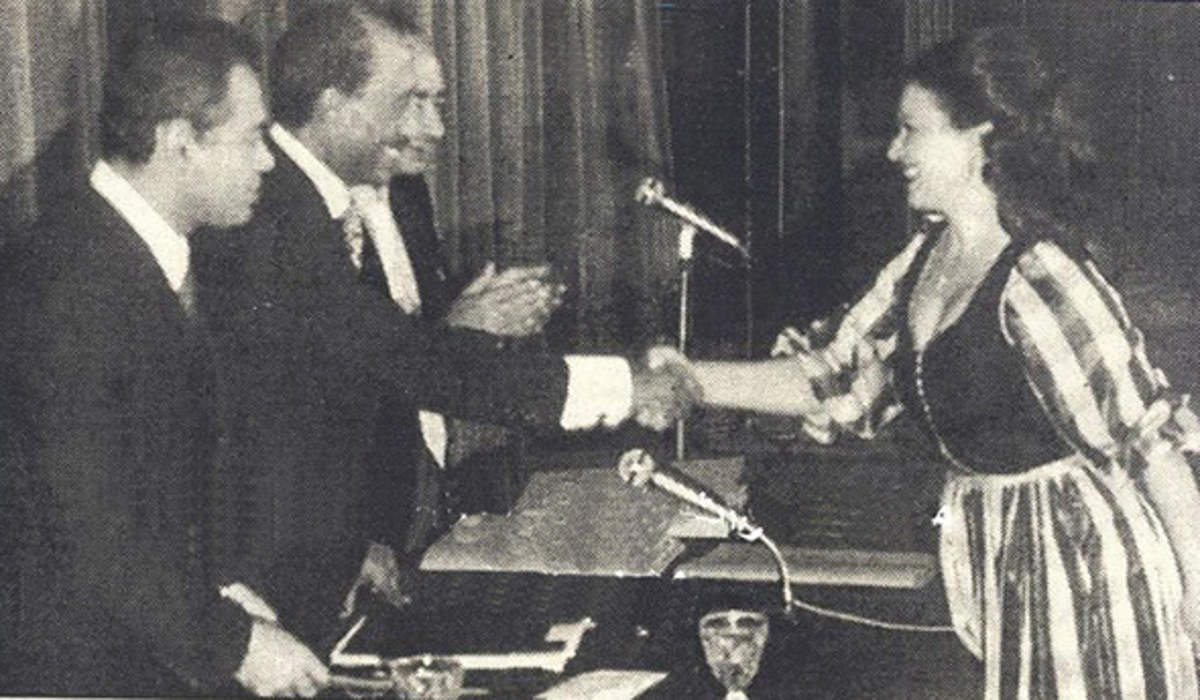

Soad Hosny receives an honor from then Egyptian president Anwar Sadat in the 1970s. (Alamy)

While that environment was far from a formal means of preparation for a life in the arts, it was, ultimately, all that Hosny needed.

“I came into film unadulterated,” she said in an interview with Qatar TV in 1972, shortly after her career defining hit “Watch Out for ZouZou,” Hassan El-Imam’s classic film about a student who falls in love with her professor. “I did not enter an institute, or anything like that. I never took a lesson.”

Hosny entered the film world early. Her debut, “Hassan and Nayima” (1959) began shooting when she was just 15. Throughout the Sixties, Hosny starred in hit after hit opposite top stars Omar Sharif, Salah Zulfikar and Rushdy Abaza, among others, finally collaborating with Egypt’s top director Youssef Chahine in 1970 with “The Choice,” by which time she had developed from a key collaborator with the film world’s biggest stars to the main draw in her own right.

“Every film I have worked on gave me more education; every experience has taught me lessons. ‘ZouZou,’ for example, was a huge success and people loved it, and if I am to continue on from that success, I don’t need to take lessons in schools to do that,” Hosny told Qatar TV in that same interview.

As the years went on, Hosny pushed for roles that would help define not only who Egyptian women were, but who they could be — pushing boundaries with overtly political films as well as biting satire that deliberately gave voice to the voiceless in Egyptian society, a move that made her a thought leader as well as a beloved cultural figure.

“I love playing the modern girl of Egypt, and expressing her problems, the environment in which she lives, and her psyche. I want to play her hopes, her ambitions, her ideas, and dreams. I want to explore what it means for us to love Egypt, and express all that that means,” she said in 1972.

Hosny was a symbol of Egyptian femininity for many, something that current Egyptian superstar Mona Zaki said she initially struggled to embody when playing her in the 2006 TV series about Hosny’s life, “Cinderella,” co-starring acclaimed Egyptian screenwriter Tamer Habib.

Mona Zaki (centre) as Soad Hosny in 2006’s ‘Cinderella.’ (AFP)

“Soad Hosny was so feminine both in appearance and substance, while I’m a tomboy. I could play Hosny’s character only after much searching. I built a new relationship with my femininity after this series,” Zaki told Vogue in 2021.

“For the Egyptian people, she was like a princess in a fairytale. That is why they dubbed her Cinderella,” Habib tells Arab News. “For two years, we used to talk about everything on the phone for hours. She felt how much I loved her, so she opened her heart to me. I was so lucky — she was truly one of a kind.”

Hosny’s peak lasted for more than two decades. But by the late Eighties she was struggling with illness, ultimately retiring from acting in 1991 at just 48.

Though she stepped away from the screen, Hosny never left the public eye. When she died in June 2001, tragically falling from the balcony of her friend Nadia Yousri’s apartment in London, England, it confounded and saddened all of Egypt, with her funeral attracting 10,000 mourners. Theories as to the exact circumstances of her death still circulate today.

Despite the enduring love Hosny has inspired over the 63 years since she first debuted on the screen, those closest to her still feel that she is misunderstood and underappreciated.

“Soad was incredibly talented. She had the ability to perfectly play any role whether it is comedic or tragic. She had charisma and charm. Yet, she was unappreciated and died alone," actor and friend Hassan Youssef told Egypt Today in 2018.

While the mere fact that interest has never faded from her life or work seems to disprove his blanket statement that Hosny was unappreciated, there is perhaps a kernel of truth in his words. After all, is it even possible to fully appreciate the nuances and variety of a life and career such as Soad Hosny’s?