VENICE: Syria’s pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale stands on San Servolo Island. Titled “The Syrian People: A Common Destiny,” it features a mix of prominent contemporary Syrian artists and a few Italian names in its representation of a country that has been embroiled in civil war and economic and social upheaval since 2011.

The pavilion this year is commissioned again by Emad Kashout, a cultural official in Damascus, who has been assisting with the selection of works for Syria’s Venice Biennale pavilion since 2015. Participants include Syrian artists Sawsan Al-Zoubi, Ismaiel Nasra, Adnan Hamideh, Omran Younis and Aksam Talla. Their work, largely on canvas, is being displayed alongside works by Italian artists Giuseppe Amadio, Lorenzo Puglisi, Marcello Lo Giudice, Hannu Palosuo and Franco Mazzucchelli. (The pavilion is funded largely by Italian sponsors.)

Omran Younis. (Supplied)

Younis’ lurid abstract expressionist paintings depict the suffering of the Syrian people with intense and vivid brushwork. As he says in his artist statement: “When art becomes a protest in this human slaughterhouse, a protest against the pain, the invisible, the human moment of fear and death that develops into screams on this white cloth until it becomes painful and the black painted lines penetrate the body of the earth like a plough to make art a clear line of certainty — it’s price is only life itself.” His work is contrasted with the softer, dreamy depictions of cityscapes and everyday life of Saousan Alzubi, as seen in her 2016 collage “Imagination City.”

Some of the works by their Italian peers do, at least, have an overt thematic connection to situations and experiences that many Syrians may recognize. Palosuo, for example, contributes two pairs of paintings; one pair a boy and girl, one pair a man and woman. All four have their faces covered with bold white brushstrokes as if to distort, or erase, their identity.

Hannu Palosuo. (Supplied)

According to Eshout, the theme of “A Common Destiny” reflects how, despite the different artistic approaches and subject matter employed by each of the five Syrian artists on show, they are united in their love for their country, a common cultural destiny, and a desire to transcend violence and chaos.

The pavilion’s press release emphasizes how Syria’s ancient heritage, with artifacts dating back to the 8th millennium BC, influenced the work on show, inspired as much by the country’s great past as by its recent horrors.

“Art culture has always represented a way to shape society by promoting love and hope,” Eshout told Arab News from Damascus. “Art in this ancient culture has always represented a way of shaping society by fostering love and hope and providing an opportunity for rebirth.”

Sawsan Al-Zoubi, “Imagination City.” (Supplied)

The Italian artists’ works are meant to complement those of their Syrian colleagues.

“They carry a message of love and peace for Syria, a land … with a strong, eclectic cultural heritage that is deeply rooted in history,” wrote Loubana Mouchaweh, Syria’s minister of culture.

But the pavilion has — as in previous years — been widely criticized by prominent members of the Syrian art community both at home and abroad for its lack of representation and failure to represent the breadth of artistic creation taking place now in Syria.

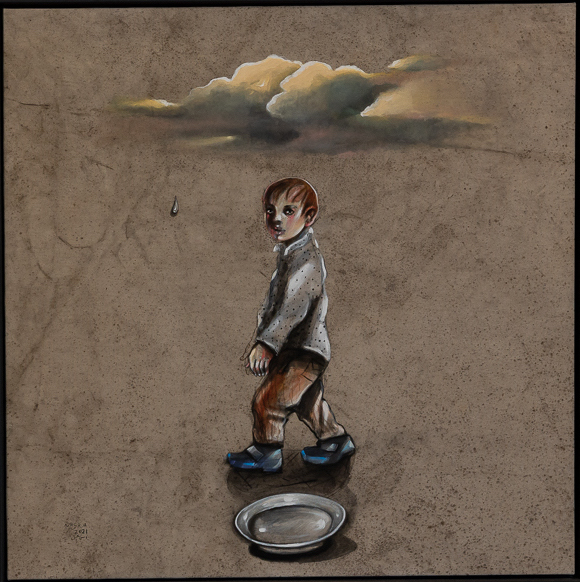

Ismaiel Nasra, “The Child and the Cloud.” (Supplied)

“It’s a small collective effort of a few people with nothing to do with the government and reflects a desperate situation for a desperate body of culture trying to exist,” said a Dubai-based Syrian arts specialist who asked to remain anonymous. “I guess we are frustrated because we know we can do more and better. But, truthfully, no one has the time and energy. There are no budgets. It is a doomed situation.”

Samer Kozah, who has run his eponymous gallery in Damascus since 1994, also said that the pavilion doesn’t offer a comprehensive representation of the Syrian art scene.

“The solution, in my opinion, is to form a special committee for international participation, including the Venice Biennale, the Ministry of Culture and active galleries in Syria, to choose the type and quality of artists,” he said.

Until then, however, it seems Syria’s representation at the Venice Biennale will struggle to fully and accurately reflect the country’s rich cultural heritage or its contemporary art scene, which still flourishes despite the country’s ongoing challenges.