KHAPLU, Gilgit-Baltistan: For residents of Pakistan’s northern Gilgit-Baltistan region, Eid Al-Fitr celebrations are incomplete without ‘rdoong balay,’ a traditional dish that is a staple on the festival that marks the end of the Muslim fasting month of Ramadan.

As Eid rolls in, the stew made of stone ground wheat, potatoes, blue and black peas and spices, is cooked in almost every household in the northern valley.

“It’s a delicious cuisine of Baltistan region which is made by nearly every family on Eid Al-Fitr,” Muhammad Iqbal Balti, a senior journalist and cartoonist from the northern region, told Arab News on Tuesday. “Without rdoong balay, there is no enjoyment.”

“I am 68 years old,” he added. “Before the 1980s, rdoong balay was cooked by families almost every week. Now it is only made on special occasions, particularly Eid Al-Fitr.”

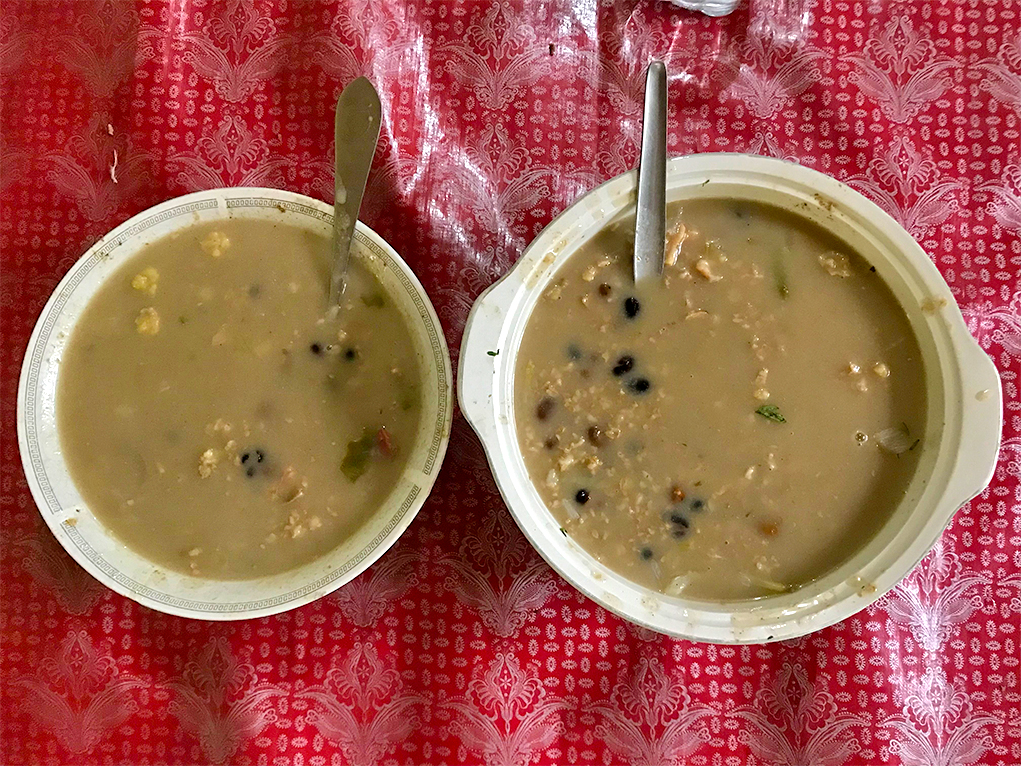

This picture, taken on May 3, 2020, shows bowls of rdoong balay, a traditional dish that is a staple of Eid Al-Fitr celebrations in Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. (AN Photo)

59-year-old Fatima, who identified herself by her first name only, said she had been making the dish since she was a child.

“When I was young and unmarried, my mother would ask me to grind wheat a day before Eid,” she said. “The cuisine becomes tastier when we use locally produced wheat and barley.”

Asked about her recipe, Fatima said she first thrashed wheat or barley with a locally made stone pestle and then poured it into a pot of boiling water. Small pieces of meat, potatoes and peas as well as spices were added next and the mixture was left to simmer for about half an hour.

A woman grinds wheat in preparation to cook the traditional rdoong balay dish for Eid Al-Fitr in Khaplu valley of Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan, on May 2, 2022. (AN Photo)

Hassan Hasrat, a local historian, told Arab News rdoong balay was made in almost every corner of the Baltistan valley, and also cooked by people who hailed from the region but lived elsewhere in Pakistan or around the world.

He said there was no written record about the origins of the dish and it was therefore difficult to determine its history or development over time.

“However, I can confidently say that this is a centuries-old dish,” Hasrat said. “This cuisine is for cold regions since it helps battle chilly weather. Almost all local dishes in Gilgit-Baltistan are suitable for cold areas.”