DUBAI: From outside, the unassuming two-story house in Irbil, capital of Iraq’s Kurdistan region, resembles a regular family daycare center. It echoes with the happy shrieks of children playing behind its high walls.

However, the compound holds a closely guarded secret: These are the children of Yazidi women who were raped in captivity by Daesh militants.

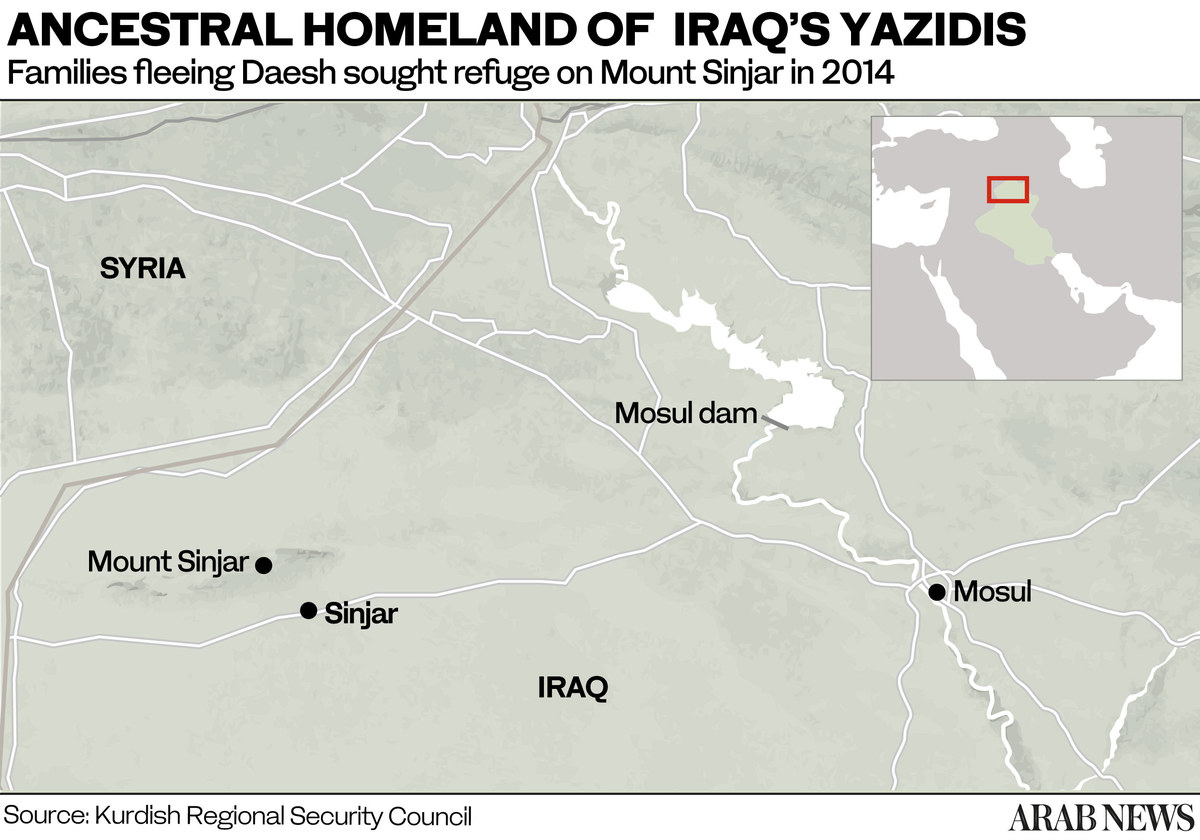

The extremists tore through Sinjar, ancestral home of Iraq’s Yazidi minority, on Aug. 3, 2014. Some families fled in terror and sought refuge on nearby Mount Sinjar, where they were left exposed to the elements, without food or water.

Those unable to escape found themselves surrounded by black-clad militants who massacred the men and sent the boys to training camps, where they were forced to convert to the group’s warped interpretation of Islam.

The Yazidi women and girls, meanwhile, were held captive, to be distributed to the militants as sex slaves and domestic servants. They were taken deep into Daesh-held territory in western Iraq and neighboring Syria, where they were sold as chattel at medieval-style slave markets.

Many chose suicide rather than submit to rape and servitude. Others would end up carrying their rapists’ children.

Following the territorial defeat of Daesh — first in Iraq in late 2017, then in Syria in early 2019 — many of the captive women and girls managed to escape or were ransomed by family and government authorities.

INNUMBERS

* 3,000 Yazidis murdered by Daesh in 2014 siege.

* 7,000 Yazidi women sexually abused by militants.

* 60,000 Yazidis now living in Germany.

While some took their children with them, others were separated from them. Physically and emotionally scarred by years of abuse, many were taken in by aid agencies or sent to other countries for specialist treatment.

The accelerated flight of Yazidis following the depredations of Daesh terrorists has brought the ancient community in Iraq to the brink of extinction.

Those women who wanted to return to their homelands following their liberation were presented with a stark choice: Abandon the children fathered by their Daesh captors or forever be exiled.

The decision by Yazidi elders to reject the children of Daesh seems callous and anachronistic to many observers. According to the Supreme Yazidi Spiritual Council, however, it is theologically impossible for anyone, including children, to convert to the Yazidi faith; they must be born to two Yazidi parents.

Iraq’s Yazidis are a symbol of the suffering caused by Daesh during its rein over vast swathes of Syria and Iraq. (AFP/File Photo)

The Yazidi form one of the oldest ethnic religious groups in the world. They are now spread thinly across the Middle East, Central Asia and Europe, having faced repeated bouts of genocide and persecution for their beliefs.

In the eyes of Daesh, the Yazidi are infidels and devil worshippers who are to be exterminated, their persecution justified by Shariah on account of their esoteric beliefs.

“While I have the utmost respect for the Yazidi religion, I believe the issue of reuniting the mothers with their children is not a religious one,” said Peter Galbraith, a former US diplomat, who has played a leading role in efforts to return children to their mothers.

“It is a fundamental human right. The mothers have the right to their children and the children have the right to their mothers,” he told Arab News.

The theological case for the rejection of the children is not the only obstacle. Another complication is Article 26 of the Iraqi Nationality Law, which stipulates that if a child’s father is Muslim the child must inherit the father’s religious status.

Displaced Iraqi children from the Yazidi community, who fled violence between Daesh and Peshmerga fighters in the northern Iraqi town of Sinjar, play in the snow at Dawodiya camp for internally displaced people in the Kurdish city of Dohuk. (AFP/File Photo)

“It is agreed by all that Daesh were not real Muslims — their twisted savagery is not a real representation of the religion,” Vian Dakhil, a Yazidi member of the Iraqi parliament, told Arab News. “Yet according to Iraqi law their children have been registered as Muslims.”

A report published in 2020 by human rights monitors Amnesty International, titled The Legacy of Terror: Plight of the Yazidi Survivors, featured accounts by several women of how they were forced to make the heart-wrenching decision of whether to give up their children or their identity.

Hanan, 24, was persuaded by her uncle to leave her daughter at an orphanage, on the understanding that she could visit whenever she wanted. But after the child had been dropped off, Hanan’s uncle told her: “Forget your daughter.”

Sana, 22, took her daughter with her when she was rescued. After daily threats, however, she decided to leave the child with an aid agency.

“In that moment it felt like my backbone broke, my whole body collapsed,” she told Amnesty.

All of the women interviewed for the report displayed signs of psychological trauma and several said they had contemplated suicide. Few have any way to communicate with their children.

Displaced Iraqis from the Yazidi community carry their children as they cross the Iraqi-Syrian border at the Fishkhabur crossing, in northern Iraq, on August 11, 2014. (AFP/File Photo)

“What happened was a real catastrophe and the women who were raped were not only victimized but also faced more problems when the children were born,” said Dakhil.

“It is a human matter; it is motherhood, despite it coming from rape. We cannot force the girls to leave or abandon their children. There must be a solution. There have been girls who were convinced that what happened to them was abnormal and so have decided to give up their kids.”

Women who were able to reunite with their children are not faring much better; they are forced to live in secrecy in Irbil, fearing for their safety should they be discovered.

In 2019, Iraq’s President Barham Salih drafted the Yazidi Female Survivors Bill, which became law in March last year. It represented a watershed moment in efforts to address the legacy of Daesh crimes against Yazidis and other minorities, as it officially recognized acts of genocide and established a framework for the provision of financial support, and other forms of redress, to survivors.

In focusing institutional attention on the female survivors of conflict-related sexual violence, the law placed Iraq among the first countries in the Arab world to recognize the rights of such survivors and take steps to redress their grievances in line with international standards.

Almost a year later, however, little has been achieved in terms of reparations for survivors.

FASTFACTS

* Yazidis revere both the Qur’an and the Bible but much of their own tradition is oral.

* It is not possible to convert to Yazidism; adherents must be born into it.

* An estimated 550,000 Yazidis lived in Iraq before the Aug. 2014 Daesh invasion.

“The vote to approve the bill has been passed; the only problem lies with actual implementation, which hasn’t really started,” said Dakhil.

“The government claims allocating money is a problem but this is unacceptable, as these people are in dire need of assistance and aid. The bill was created for this issue. We will try our best to implement it fully.”

Pari Ibrahim, director of the Free Yazidi Foundation, told Arab News: “The issue of those Yazidi women who have children born from rape is the most challenging one for the Yazidi community.

“Our position, as a Yazidi women-led organization, is that the final decision of the individual survivor is more important than any other view, including those of family members or religious leaders.”

Several of the women want to move to Australia to live with other Yazidi survivors. The Netherlands is also touted as a potential option. However, border restrictions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic have slowed the asylum process.

Members of Daesh parading with a tank in a street in the northern rebel-held Syrian city of Raqqa. (AFP/Handout Welayay Raqa)

“The best solution is for them to be resettled abroad in another country, where they can live without stigma,” said Ibrahim.

“But no matter what, their rights and their wishes should be respected after all the suffering they have endured. This issue is intensely painful for the Yazidi community — but not more painful than the trauma inflicted upon Yazidi survivors. We must respect and defend their rights.”

For those women and children spurned by their community, neglected by the state and confined to an anonymous compound in Irbil, few options remain other than to wait and hope for an opportunity to leave their tainted homeland behind for good.

“I think the solution lies with international states and humanitarian (nongovernmental organizations),” Dakhil said. “These women should be taken abroad where they can live without fear.”