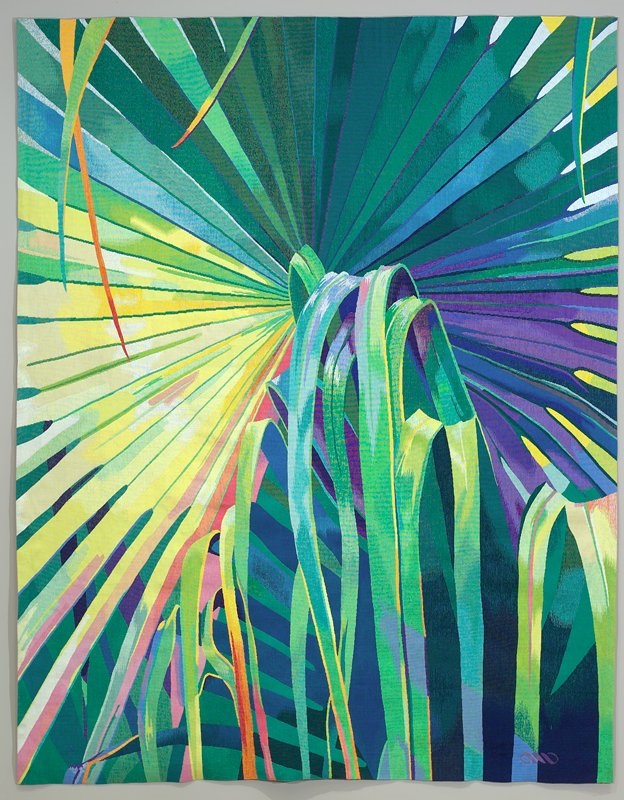

DUBAI: A large woven installation echoes the shapes of palm trees viewed while lying down on the ground. “Palm,” placed in Prince Faisal bin Fahd Arts Hall in Riyadh for Misk Art Week’s exhibition “Here, Now,” was created by American contemporary artist Sheila Hicks. It was originally conceived in Riyadh’s King Saud University, where Hicks set up an art program in the 1980s.

Hicks recalls the pleasurable moment of lying down, looking up at a palm tree and seeing a mass of leaves spanning out above her. The joy of looking at the parallel reality created by its leaves became the basis of Hick’s tapestry “The Palm Tree” (1984-85), made in wool, cotton, rayon, silk, and linen. The piece on view in Riyadh follows centuries-old weaving methods established at the Aubusson workshops in France and presents the artist’s ability to translate a personal, intimate moment into the physical and public realm with grace and ease.

Sheila Hicks, Palm, 1985, wool, weave tapestry, 358.1 x 281.9 cm. (Here, Now / هنا، الآن , October 3, 2021 – January 31, 2022. (Courtesy of the artist and Misk Art Institute)

“During my time in Saudi Arabia in the 1980s,” Hicks said, “on a field trip with various architects involved in designing King Saud University, I looked up to the sky and was struck by the splendor and size of the palm tree that was protecting and shading us. ‘Palm,’ the tapestry on show as part of ‘Here, Now,’ is inspired by this specific palm tree.”

The original work is hanging in the main auditorium of the King Saud University in Riyadh. Other versions of the work are in several international collections, including The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Hicks’ dreamy work, recalling the beauty of Saudi Arabia’s desert landscape, is one of several pieces by Saudi and international artists in the show responding to notions of individual and collective identity and how these respond to society, as well as to a particular space or place, be it public or private. Curated by British writer Sacha Craddock in collaboration with Misk’s assistant curators Alia Ahmad Al-Saud and Nora Algosaibi, the exhibition also features paintings, textiles, sculptures, digital works and immersive installations by Saudi artists Filwa Nazer, Manal AlDowayan, Yousef Jaha and Sami Ali AlHossein, the Saudi-Palestinian Ayman Yossri Daydban, Piyarat Piyapongwiwat from Thailand, Salah ElMur from Sudan, Vasudevan Akkitham from India and the South Korean Young In Hong.

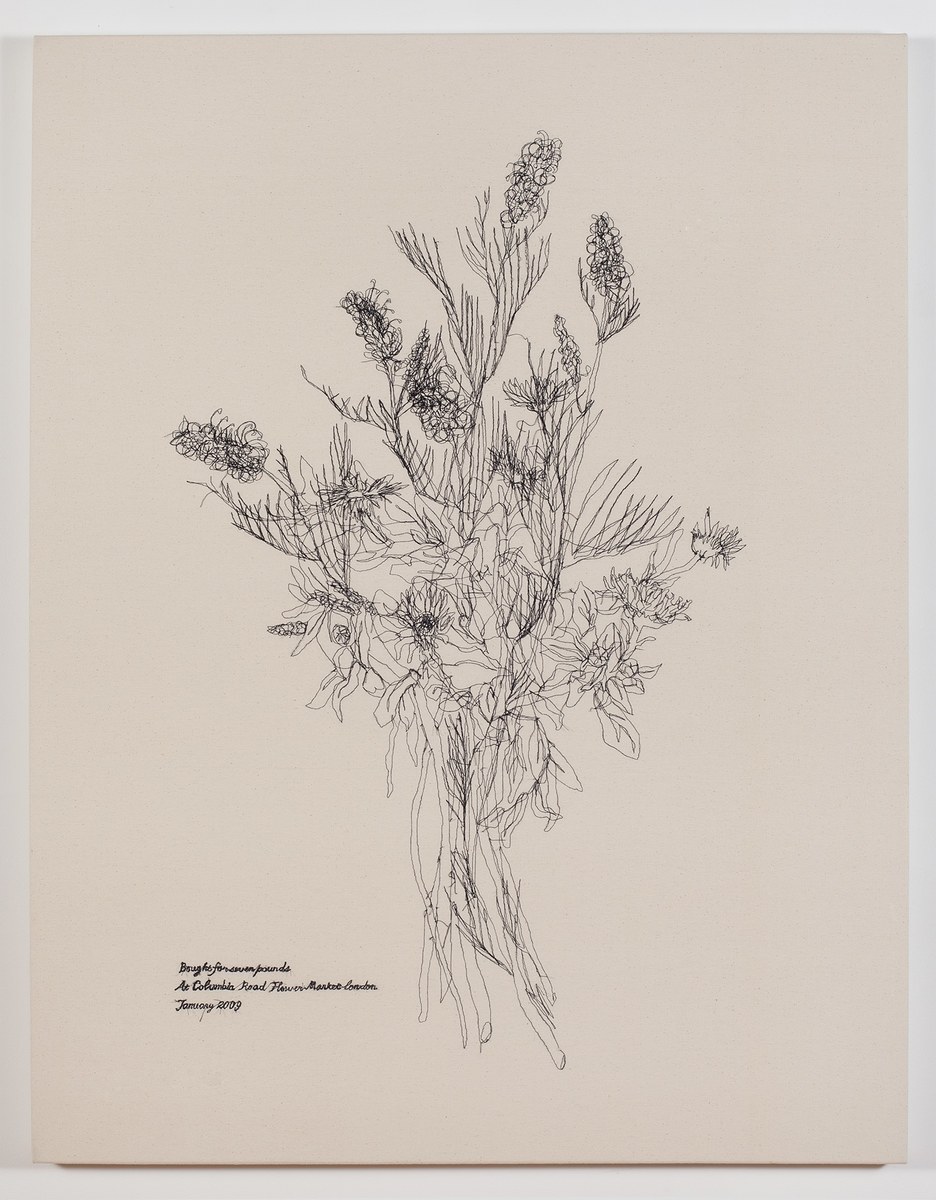

Young in Hong, Flower Drawing (Columbia Road, London), 2009, embroidery on cotton, 116 x 89x3 cm. (Courtesy of the artist and Misk Art Institute)

“I hope that the exceptionally fluid and open process that brought ‘Here, Now’ together is mirrored by the experience of the audience,” said Sacha Craddock. “Layers of curatorial knowledge and familiarity, on my part, have merged with totally new influences, innovations and traditions to produce a sense of perpetual discovery for all.”

“I Am Here,” a large-scale piece by Manal AlDowayan, encourages visitors to participate in the work. Paint and stencils are offered so that viewers can themselves write the artwork’s title — I Am Here — on one of the gallery’s walls. Over time, the painted words gradually disappear under new words, offering a visual commentary on the delicate relationship between the individual and the collective, as well as the ephemeral nature of time and existence.

The interactive maze-like sculpture by Saudi-Palestinian artist Ayman Yossri Daydban entitled “Tree House” (2019) is a large-scale work positioned against several walls. It seeks to deconstruct archetypal narratives related to cultural heritage and identity, as well as the Middle East’s historical relation to Western colonial powers, through its multitude of cut-out forms, Daydban’s thought-provoking work stems from the subjective nature of words and language. The artist believes that even after the function and meaning of an object moves on, its material base — in essence its core form — remains.

Filwa Nazer, The Other Is Another Body 2, 2019, polyethylene industrial netting and cotton, 292 x 83 x 240 cm. (Courtesy of the artist and Misk Art Institute)

An installation work by Filwa Nazer, another Saudi artist, entitled “The Other Is Another Body,” which was commissioned by Sharjah Art Foundation in 2019, features a pair of sculptures covered in black netting that, according to Nazer, “evoke a female presence and embody the spirit of the in-between in its various contradictions.” She intends the sculptures to be “at once vulnerable and strong, abstract and concrete, protected and exposed, connected yet separated.” Nazer’s intent was to show sculptures in “the state of becoming in all its fragility and awkwardness.”

Nazer’s work, which ranges in medium from digital print to collage, textile, and photography, addresses question of emotional identity regarding social and spatial context.

“My work relates to my emotional or psychological interaction with my themes and concepts,” she said. “Research is an integral component of my artistic practice: reading, field research, collecting material and stories. My lines of inquiry always stem from a desire to question things. Through my research, previously unseen connections between various elements start emerging, and then begins the process of experimental creation.”

The diversity of the works on show is further exemplified in paintings by Saudi artist AlHossein and the Sudanese ElMur. The former’s abstract paintings depict the idea of personal memory as a landscape while ElMur’s at once endearing and profound works on canvas depict subjects confused by reality as we know it and a new three-dimensional space — perhaps the influence of today’s rapidly expanding technological realm.

As the works in “Here, Now” demonstrate, the spaces occupied by the personal and the public are subjective—at the whims of one’s perception, dictated by their own personal context and the intention that they apply to the people and spaces they occupy in real-time—in everyday life.

Here, Now / هنا، الآن , October 3, 2021 – January 31, 2022, miskartinstitute.org