IRBIL: When explosive-laden drones targeted a US military base inside Irbil International Airport in Iraqi Kurdistan late on Saturday, the story got buried by reports about the memorials commemorating the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks on New York and Washington.

But to observers of Iraq, the incident in Irbil was the latest shot fired across the bows of a prime minister who is determined not to play into the hands of political adversaries and malign actors as he charts a course that differs significantly from those of his predecessors.

Take the Baghdad Conference for Cooperation and Partnership hosted by Mustafa Al-Kadhimi on August 28. It was attended by high-level delegations from France, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Iran, Turkey, Egypt, Qatar and the UAE in addition to the general secretaries of the Arab League, the Gulf Cooperation Council and the Organization for Islamic Cooperation.

That the Iraqi PM managed to bring so many heads of governments and organizations under one roof, even if for only one day, was undoubtedly a major diplomatic achievement.

Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa Al-Kadhimi listens as US President Joe Biden speaks during a bilateral meeting in the Oval Office at the White House on July 26, 2021. (AFP/File Photo)

The assurance of support from the international community that Al-Kadhimi evidently enjoys is something that eluded his predecessors — Adel Abdul-Mahdi, Haider Abadi and Nouri Al-Maliki — and will probably continue to be his strong suit going forward.

Few things are more daunting than having to steer the ship of state in a part of the Middle East riven by sectarian and political conflict. But being seen as a rare safe pair of hands means that true friends of Iraq, mindful of the competing interests that Al-Kadhimi has to juggle, are willing to cut him some slack, particularly in how he deals with the challenge posed by militias.

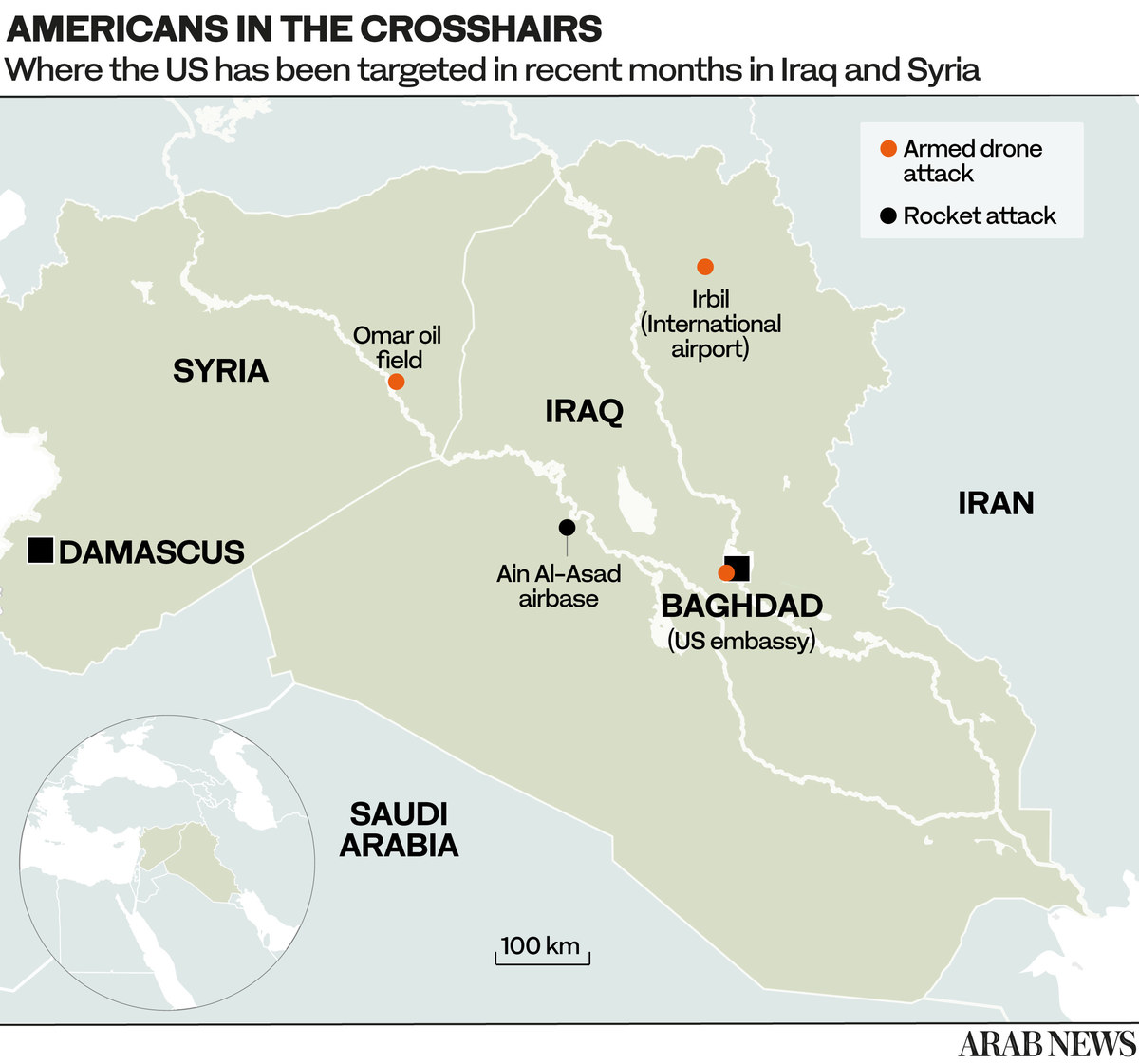

As usual, no group claimed responsibility for the Sept. 11 night Irbil attack, but it was at least the sixth time that drones or rockets had targeted the heavily fortified site in the past year. The US blames the assaults on the Shiite-majority Iraqi Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), paramilitary groups that strongly oppose the presence of American troops in Iraq.

In addition to harassing the Biden administration, analysts say, elements within the PMF are intent on influencing the outcome of the Iraqi general election next month, and undermining a carefully constructed ceasefire arranged by the government in Baghdad.

“This attack is a message from the militias directed at the United States, which is to withdraw from Iraq, and quickly,” said Nicholas Heras, a senior analyst at the Newlines Institute, a nonpartisan think tank in Washington.

Noting that the attack was not particularly destructive, he added that it signaled “that the US should expect more of these strikes until it leaves Iraq. It presents an unwelcome complication to US policy on Iraq and Syria at a time when the Biden team is trying to manage the political rancor over the withdrawal from Afghanistan.”

There are at least 2,500 US troops in Iraq, most notably in the capital, Baghdad, and at the Ain Al-Asad Air Base in Anbar province. The base in Irbil is an important logistical hub, supporting the military presence and anti-terrorism operations in neighboring Syria.

In July, President Joe Biden and Al-Kadhimi agreed to end the US combat mission in the country by the end of this year. The remaining troops will continue to assist Iraqi and Kurdish military forces in an advisory role.

The drone assault on Saturday was the latest in a series of often ineffective, sometimes lethal, politically motivated strikes. The first attack on Irbil airport took place on Sept. 30 last year, when six rockets were fired at it.

They did not cause any casualties or damage but they clearly demonstrated that American troops could be targeted in Iraqi Kurdistan, a largely stable autonomous region controlled by the pro-Western Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).

On Feb. 15 this year another barrage targeted the airport, this time using 14 rockets, many of which landed in nearby residential areas. A civilian contractor and a Kurdish civilian were killed and eight people were injured.

On April 14, drones packed with explosives were used in an attack in the region for the first time, but there were no casualties. On June 26, a drone attack damaged a house on the outskirts of Irbil, a stone’s throw from the site where a new US consulate is being built. On July 6 another drone attack targeted American troops at the airport, but again there were no reports of casualties or damage.

Analysts have suggested the recent attacks might be deliberately designed to avoid causing US fatalities so that militia factions can be seen to be actively resisting the US military presence without provoking any large-scale retaliation.

Joel Wing, author of the Musings on Iraq blog, believes the intention of the most recent attack in Irbil was to undermine a ceasefire agreement arranged by Iraqi National Security Adviser Qasim Al-Araji. He announced on Friday that the government had reached a two-stage truce with the militia factions that have been targeting US troops.

The first stage envisions the cessation of hostilities until after the parliamentary elections on Oct. 10, so that Iraqis can vote in a secure and stable environment. The second stage is supposed to run until the end of the year, when the US combat mission in the country is due to formally end.

Al-Araji had “just announced he had (arranged) a ceasefire with these factions and then one group carried out this attack to thumb its nose at him,” Wing said.

He added that the central government in Baghdad and the Irbil-based KRG are trying to stop the attacks. They have increased security and intelligence efforts in the unstable, disputed territories from which the militias carry out many of their strikes. Despite this growing cooperation, however, countering drone and missile strikes is difficult.

“The security forces have found some rockets before they have been launched, but there is no real protection from drones because they can be launched from anywhere within the device’s range,” Wing said.

Al-Kadhimi has adopted a cautious yet pragmatic approach to government efforts to reduce the power of the PMF factions, while seeking to avoid a showdown that could lead to a violent conflict. He has, for example, earned praise from powerful Shiite parties by sealing the deal to end the US combat mission.

Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa Al-Kadhimi, right, receives Dubai’s Ruler and UAE Vice President Mohammed bin Rashid Al-Maktoum on his arrival for the Baghdad regional summit. (Prime Minister’s Media Office/AFP)

Substantive or stylistic, these policy adjustments have differentiated Al-Kadhimi from his predecessors, who were widely viewed as failures when it came to navigating the region’s treacherous political waters.

At the same time, Iraq’s nascent reputation as a mediator capable of bringing together regional rivals around the same table is expected to have a positive influence on Al-Kadhimi’s standing in domestic politics despite the sharp divides.

This is not to say that the going has been easy for Al-Kadhimi. In June last year Kataib Hezbollah, one of the militias under the PMF umbrella, tried to intimidate him inside Baghdad’s Green Zone, the center of Iraq’s political life, even mounting a show of force outside the prime minister’s residence. This was intended to put pressure on the government to release Kataib members arrested for plotting a rocket attack on the US embassy.

In May this year, another group of PMF fighters staged a show of strength in the Green Zone and succeeded in forcing the country’s elected leaders to release a militia commander who had been arrested in Anbar.

Abdulla Hawez, a Kurdish-affairs analyst, said that Saturday’s strike differed from previous incidents in that it came after the US and Iraq had agreed to end the combat mission, and after the militias said they would cease their attacks. He also pointed out that on this occasion the militias did not launch attacks on US interests elsewhere in Iraq.

“The message appears to be different from the other attacks — this is more Kurdistan-specific,” he told Arab News. “This one might have been a warning to the KRG that these factions will not accept the US staying in Kurdistan if there is any such attempt through US-KRG dialogue or through backchannels.”

Could the militias behind the attacks also be looking to appeal to their supporters ahead of next month’s vote?

“Anti-KRG rhetoric is popular in the south, but this alone is unlikely to tip the balance in favor of the militias, especially given that people nowadays care more about basic services and the economy and less about sectarian politics,” Hawez said.

No matter what the perpetrators of the Sept. 11 Irbil attack intended, it is unlikely to have gone down well with Iraqis who are focused less on politics and more on the basic necessities of life.