DUBAI: Since Lebanon’s currency collapsed in October 2019 — thrusting the nation into its deepest economic crisis in recent memory — a growing number of its citizens have been forced to rely on private generators to power their homes. The alternative is to go without electricity for several hours every day.

Earlier this month, Karpowership, a Turkish energy company responsible for around a quarter of Lebanon’s electricity supply, turned off its generators, claiming that the debt-burdened Lebanese government owed it millions of dollars in unpaid dues.

Faisal Al-Sayegh, a Lebanese MP, had warned in March that “two Turkish steamboats that were hired by the Ministry of Energy to generate electricity are to withdraw from Lebanon because they did not receive their dues, which are about $160 million.”

Now, in a development that could leave millions more in the dark, cash-strapped Lebanese authorities are looking to suspend state subsidies from the end of May for fuel and electricity.

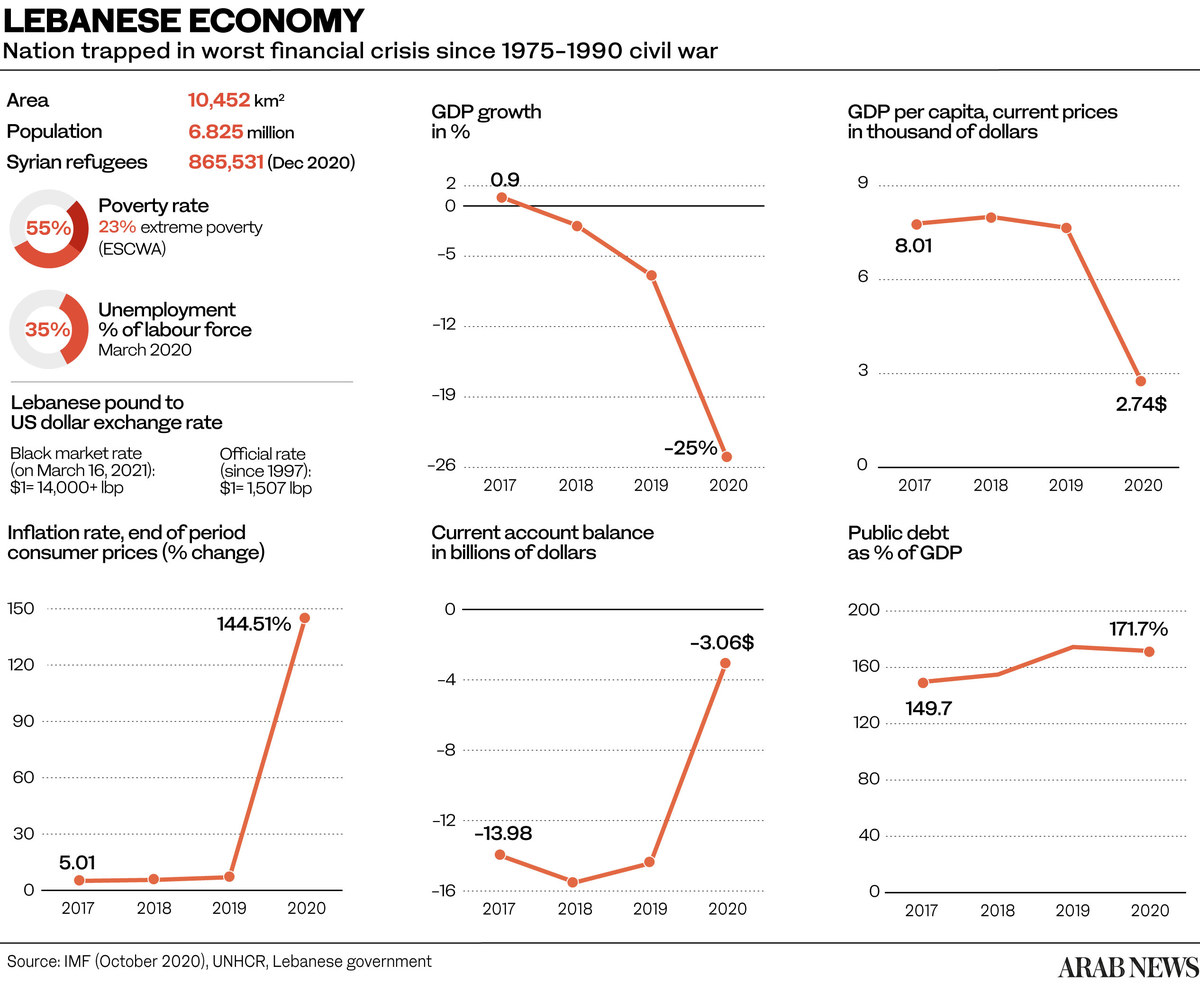

Successive governments of Lebanon, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have deemed electricity reform a vital issue for reducing the country’s public debt, which has soared to more than 150 percent of the GDP.

Net transfers to the state-owned Electricite du Liban per year are between $1 billion and $1.5 billion, most of which is spent on the purchase of fuel.

On Wednesday, S&P Global said the cost for Lebanese banks to restructure debts could range from 30 percent to 134 percent of the GDP for 2021. “The main stumbling block to restructuring appears to be that Lebanon is currently functioning with a caretaker government without authority to agree terms with creditors,” an S&P Global report said.

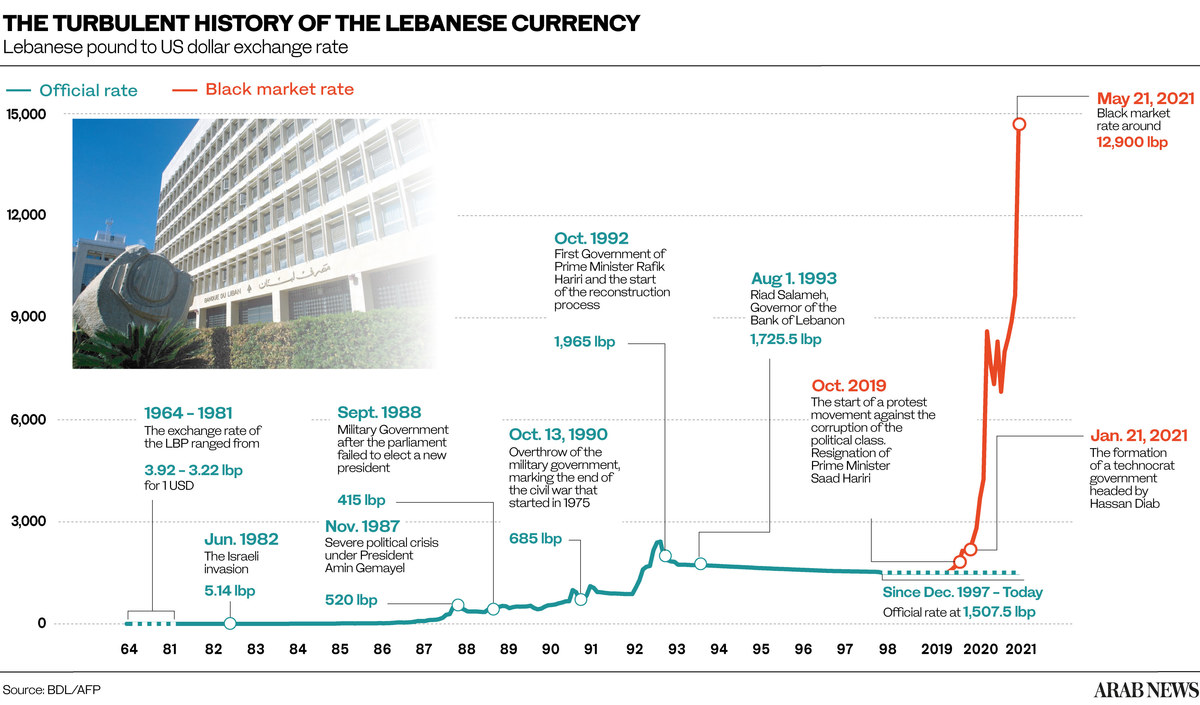

Lebanon’s financial meltdown, its worst since the 1975-1990 civil war, has triggered months of social upheaval. According to the World Bank, real gross domestic product (GDP) growth contracted by some 20.3 percent in 2020 and inflation reached triple digits.

The value of Lebanon’s currency keeps on plumbing new depths while extreme poverty continues to rise sharply owing to the economic shock of the coronavirus pandemic and the Beirut port blast of August 2020.

To escape misery and hardship, young Lebanese are following in the footsteps of a previous generation, leaving their country in search of work and better opportunities, while hoping to be able to send home a part of their wages to keep their families afloat.

Nevertheless, for some observers the dark clouds of economic doom carry a potential silver lining — invigorating a trend towards decentralization, allowing the private sector to fill the void left by an ineffective state.

Roy Badaro, an independent Lebanese economist and a member of the team responsible for drafting a proposal on how to gradually remove subsidies from government spending, believes the shutdown of Turkey’s Karpowership will lead to “more decentralized electricity in the form of private generators and/or private companies running the generators.

“This in turn could lead to a more decentralized economy as well as a more decentralized political administration,” he said. “Not removing subsidies today will make us even poorer in 12 to 18 months.”

However, according to Badaro, the process of scrapping subsidies will be gradual, and will not extend to other critical commodities like medicines and wheat.

For months now, the Lebanese government has been dipping into the public’s private bank deposits to fund its subsidies — by no means a limitless resource.

Decentralized solutions to spiraling food prices and unreliable electricity could break the political gridlock in Lebanon, experts say. (AFP)

“This policy of taking out depositor’s money to fund other government means and subsidies is clearly disastrous and has been going on for months and months. But the end game is approaching, and we will run out of reserves at some stage,” Adel Afiouni, a former investment banker and expert in international capital markets and emerging economies, told Arab News.

“The currency will keep dropping and we will need to get foreign currency at a very expensive price. We’ll end up with even more currency collapse, hyperinflation and even more poverty. Accessing hard currency will become difficult for 90 percent of the population except for those that can finance themselves through aid or a job abroad. Now there is no road back to salvage this situation.”

To ration its dwindling foreign currency reserves, the central bank has called on the caretaker government to gradually lift its system of subsidies. Badaro’s team has recommended a minimum salary subsidy of $125 per month that is “adjustable every month due to the high volatility of the exchange rate.”

However, the plan will have to be approved by parliament before it can be implemented.

Experts say an emergency injection of liquidity into the Lebanese banking sector from an external source would be a sorely needed shot in the arm.

“The emergency injection would need to be from the IMF, but that is not happening and has been aborted for the last year and a half,” said Afioni.

Lebanon’s current predicament could have been largely avoided had an agreement with the IMF been reached. But talks have long been stalled.

On March 25, the IMF said a new Lebanese government must carry out far-reaching economic reforms in order to pull the country out of its financial crisis.

“It is critical that a new government be formed promptly with a strong mandate to implement the necessary reforms,” Gerry Rice, an IMF spokesman, said at the time. “The challenges facing Lebanon and the Lebanese people are exceptionally large, and that reform program is badly needed.”

In the absence of foreign intervention and political consensus on a workable solution, Lebanon continues to plunge deeper into the abyss. Experts believe the situation could get far worse before it gets any better.

“Things can keep collapsing — there is no bottom and if you look at the history of some of the countries that went through crises, such as Venezuela and Argentina, every day that passed by without decision-makers taking proper decisions, things became worse and worse,” one Lebanese political analyst told Arab News on condition of anonymity.

“With no agreed masterplan to fix the situation, no fresh dollars coming into the country and subsidies gradually being phased out, there will be more social unrest and we will move from the Argentinian model to the Venezuelan and then to the Somalian.

“Today, no one is accountable in Lebanon. The only way to fight corruption is to clean up the public space. If politics remain centralized, Lebanon will remain corrupt.”

Successive governments of Lebanon, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have deemed electricity reform a vital issue for reducing the debt, which has soared to more than 150 percent of the GDP.

Quite what form the collapse will take is a point of conjecture among experts, but many believe the system, which increasingly follows a model of clientelism, must implode before it can rise anew.

“I am not sure we are at the end of our race to the bottom just yet,” said Badaro. “A big event will come soon. We need a game-changing event that will shake up the situation in Lebanon, and we expect that to come before the end of year. Then there will be a rebirth. We’ll need to find a new system.”

Amid the despair and uncertainty, one thing is certain though: Crisis-wracked Lebanon faces many more months of darkness, both figurative and literal, before it can expect a turnaround.

“Yes, we could have more darkness,” said Badaro. “But darkness in Lebanon is not due to the shutdown of the Turkish company but to the darkness of our minds.

“When you start building a state, you need some moral values and that is what is now lacking in our leadership. We need to enlighten the minds of the people to start doing things differently at the political and social levels.”

His opinion is seconded by Afiouni, who believes the roadblock is political in nature, with official inaction condemning Lebanon and its economic trajectory to a state of paralysis.

“The sad reality is that as long as there is no government in place that has the competence and expertise to address the crisis, we will sink lower and lower,” Afiouni told Arab News.

“Without a competent government, Lebanon’s collapse is unstoppable.”

Twitter: @rebeccaaproctor