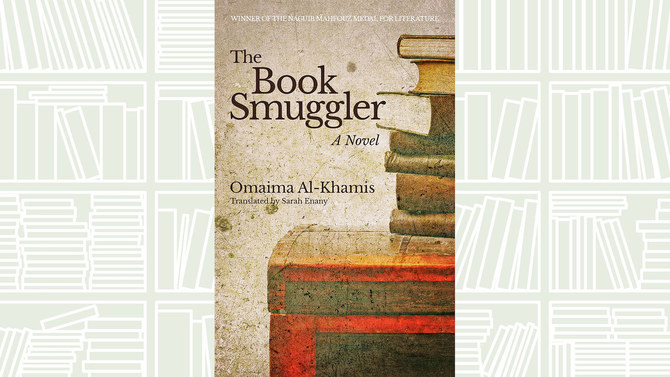

CHICAGO: In 2018, Riyadh native Omaima Al-Khamis won the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature in for her work of historical fiction, “The Book Smuggler,” an extraordinary tale set in the 11th century CE, in the Golden Age of Islam.

The book, newly translated into English by Sarah Enany, follows Mazid Al-Najdi Al-Hanafi, a scribe and bookseller from the village of Hijr Al-Yamama on the Arabian peninsula, who embarks on a journey to see the world and feed his great passion for learning.

The story begins three years after Mazid leaves his home. The Islamic world is in constant transition between dynasties (the Fatimid, Umayyad, and Abbasid) and political and religious groups as civil wars and conflicts engulf the region during the Era of Sedition.

Mazid discovers that although many people share his love of learning and discovery, other equate it to blasphemy. Books and manuscripts of great thinkers — Al-Mutanabbi, Al-Isfahani, Abu Hayan, Al-Kindi, Ibn Haytham, the Greek philosphers and others — are under threat of being burned and lost forever. Mazid, whose career as a bookseller puts him in a precarious situation, must transport his treasures from Baghdad to Jerusalem and Cairo to Andalusia in secret, spreading knowledge of the scientific and philosophical works he is committed to protecting.

The way that Al-Khamis captures the era is reminiscent of the great Lebanese-born French author Amin Maalouf — filled with vivid descriptions, incredibly detailed history and a vibrant lightness that brings the age to life. Through Mazid, a man of little means but great heart, Al-Khamis enthralls her readers with an epic tale exploring history and its heroes as Mazid sits in on discussion circles at the mosques of every city he visits to hear about the events of the time and their protagonists and antagonists. As his world begins to change, Mazid finds himself shedding the innocence of youth and becoming a man who is driven by his desire for knowledge.

Through her perfectly paced, patiently illuminating tale, Al-Khamis pays homage to a deep-rooted history, one that is tense and joyful, in which the passion of men and women outweighs the fear of the time and those who want to control thoughts and lives.