KARACHI: Fifty years ago, Akbar Hussain walked into Dhaka Cricket Stadium with his Bell and Howell camera to film a four-day Test match between Pakistan and a World XI.

The crowd was cheering, and everyone looked excited. But then the mood suddenly changed and the match was called off amid violence as two prominent Pakistani cricketers, Wasim Bari and Sarfraz Nawaz, were building a partnership.

“I was not sure what was happening,” Hussain told Arab News, speaking about the incident that took place on March 1, 1971.

Just months earlier, Pakistan had held its first general elections, in December 1970, which were won by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s Awami League party.

Passions were still running high, though things looked normal to Hussain, who could not figure out why everyone around him had become so furious.

“They set tents on fire and started pelting stones at players, who rushed to the dressing room to save their lives,” he said. “Several shops were burnt outside the stadium as rioting continued.”

Hussain, who at the time worked as a cameraman with the Dhaka television station before moving to Karachi in 1973, later discovered that the provocation was caused by a radio broadcast about the cancelation of a National Assembly session scheduled in Dhaka.

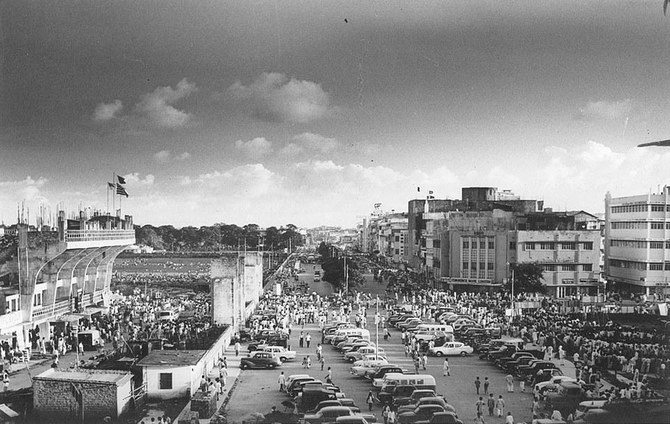

Crowds of people came out in the streets of the city in protest, and stores and business centers in the city closed. The cricket match between Pakistan and the World XI was suspended as audiences left to take part in the protests.

Ghulam Mujtaba, a former banker who was also among the audience, said it was “total chaos.”

“The stadium where people were cheering for their favorite players a little while ago was now on fire,” he told Arab News. “The news bulletin had turned the sporting arena into a battlefield after the radio announcement spread like a wildfire.”

Intikhab Alam, the skipper of the Pakistan team that came under attack, recalled the “horrible story,” telling Arab News that he had just returned to the pavilion when the rioting began.

“The World XI was fielding, so its players ran to take refuge,” he said. “Some went to their dressing room, others came to ours. For about two hours, we could not get out of the stadium.”

The foreign cricketers reached the Intercontinental Hotel where they were staying. Things were difficult for the Pakistani players, however, since their accommodation was further away from the stadium and they had to temporarily stay at a nearby guest house.

“The phone lines were dead,” Alam said. “Our team remained there until midnight and reached the hotel at 1 a.m.”

The former Pakistani captain added that World XI was lucky to board an empty Pakistan International Airlines flight for Lahore.

“We got stuck and could not go out of our hotel,” he added.

The situation lasted several days until arrangements were made to ensure the safe movement of local cricketers.

“Our jeep was escorted by a police truck that took us to the airport, which was hardly 20 minutes away from our hotel,” he said. “However, our journey continued for about two hours since the network of roads was littered with smashed cars and burning tires,” he said.

Alam said this was still not the end of the team’s agony.

Since Pakistani flights were not allowed to move through Indian airspace, the cricket squad had to take a detour and go to Sri Lanka first.

Just as the plane touched down at the Colombo airport, its tire burst. The team was due to play its last Test match against the World XI in Lahore, but almost missed the clash.

“The airlines added extra seats for us on the connecting flight to Lahore after we reached Karachi,” the former captain said. “By the time we reached our destination, the match had been postponed due to rain. That is how we managed to play the game.”

Despite the shocking incidents, the two teams were still willing to finish the series.

“Sportsmen think differently,” Alam said. “They try to send out the message of peace and are willing to play in difficult circumstances to make that happen.”