KARACHI: In a first for Pakistan, Christian members of Karachi city’s transgender community, who for years have complained of religious discrimination, got a church of their own after a pastor invited them to her home where she has dedicated a small corner for church services.

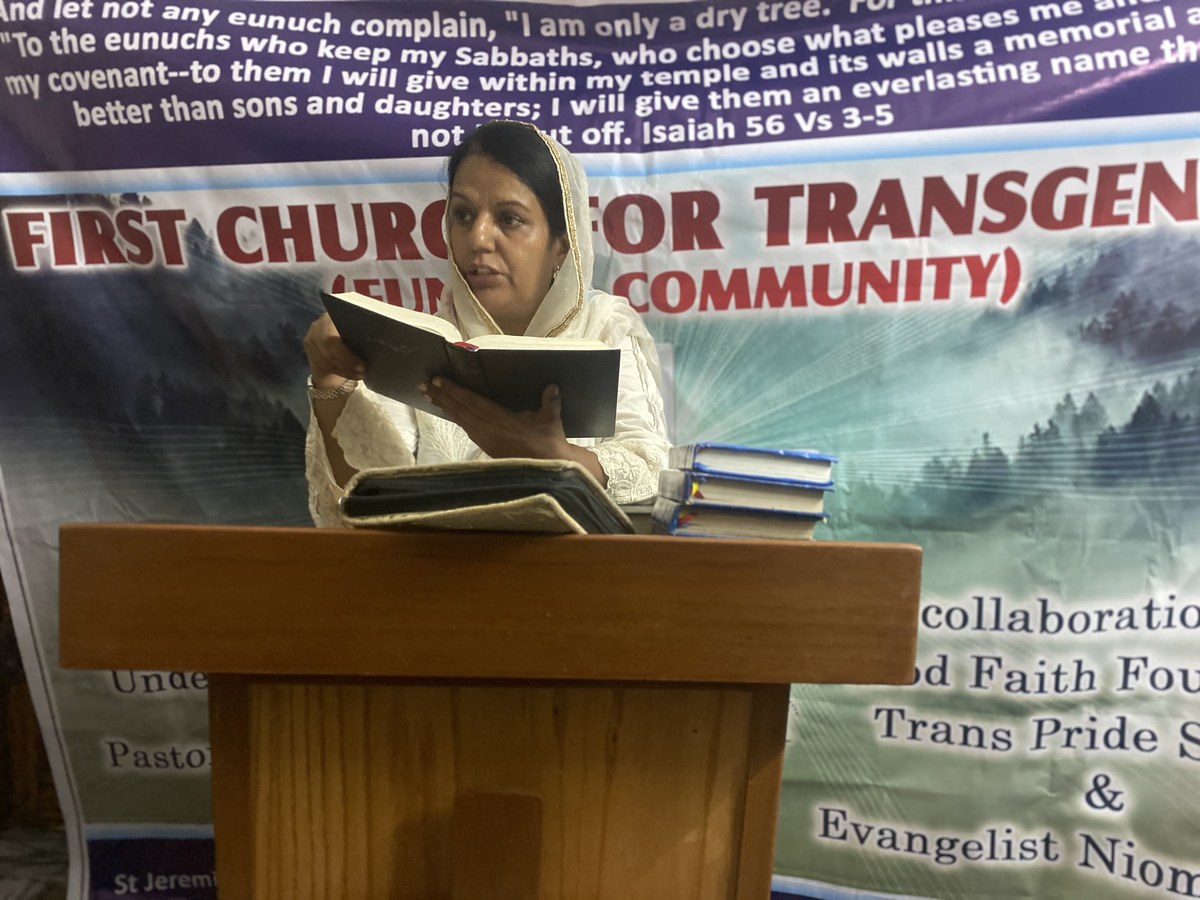

Pastor Ghazala Shafiq reads the Bible at a small church set up at her residence for transgender Christians, in Karachi, Pakistan, on August 21, 2020. (AN Photo)

Pastor Ghazala Shafiq inaugurated the modest faith center on August 14, Pakistan’s Independence Day, hoping to provide some religious respite to members of the trans community, many of whom complain they are not allowed to enter regular churches or touch the bible.

“No one was willing to pay heed to their problems, though they opened up to me and shared their stories,” the pastor said.

Pastor Ghazala Shafiq reads the Bible at a small church set up at her residence for transgender Christians, in Karachi, Pakistan, on August 21, 2020. (AN Photo)

According to the 2017 census, the country has 10,418 transgender people out of which 24 percent— or 2,527— live in the southern province of Sindh. The number of them who are Christians is unknown though Shafiq said around 2,000 transgender Christians lived in Karachi.

Last Friday, about 30 of them visited Shafiq’s makeshift church to perform their religious rituals.

Pastor Ghazala Shafiq reads the Bible at a small church set up at her residence for transgender Christians, in Karachi, Pakistan, on August 21, 2020. (AN Photo)

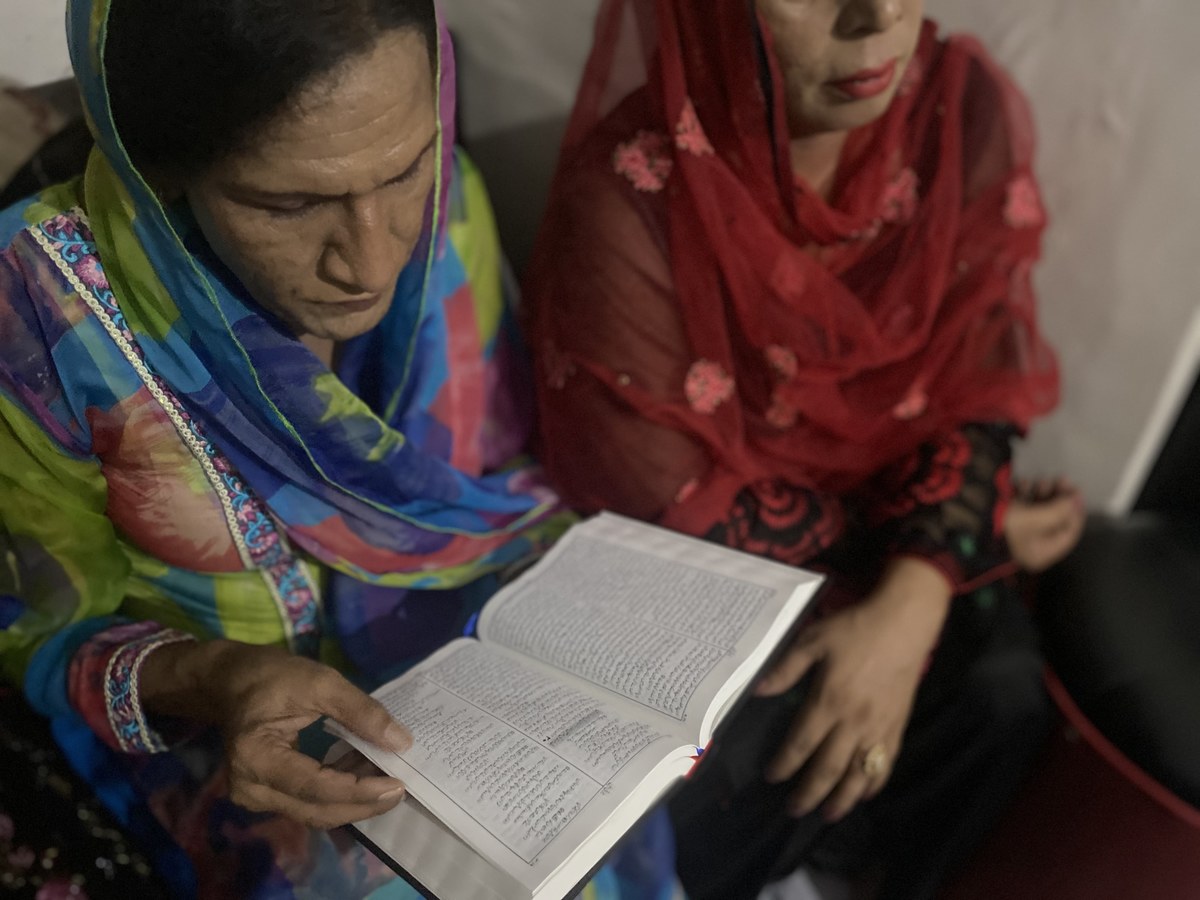

“It’s like a dream come true. I can actually hold the Bible,” 40-year-old Nasira Gill, who attended the service, told Arab News while holding the holy book in her hands.

“No one ever came to our rescue before, neither our parents nor any church,” she complained, adding that she was always inclined toward religion but had to sit on the back benches whenever she visited a church to avoid harassment.

Pastor Ghazala Shafiq speaks to Arab News in a church for transgender Christians in Karachi, pakistan, on August 21, 2020. (AN Photo)

“People looked at us as if we had committed a crime,” she said. “Everyone tried to tell us the right way of following our faith. Some of them insisted that we were women and must cover our heads with a shawl while others believed that we were men and should pray bareheaded.”

Bushra, another transgender woman who only uses her first name, said people’s attitudes were pushing hundreds of her community members away from their places of worship.

Nasira Gill, a transgender women, reads the Bible during a Friday prayer service at a church established for transgender Christians in Karachi, Pakistan, on August 21, 2020. (AN Photo)

“People had problems with where we sat,” she told Arab News. “Traditionally, there are separate rows for men and women in Pakistani churches. That leaves us with no space of our own since people kept objecting on why we were occupying one row or another.”

“Some people believed that transgender persons were dirty and should not touch the scripture,” Shafiq said. “This is despite the fact that Christianity gives them equal rights to pray in churches. God has made a special place for them and they are part of our society. We have to deal with them like our other children.”

Shafiq said that all these issues made her realize that transgender Christians deserved a church of their own.

“Many people have applauded the initiative,” she said about the church she has opened in her home. “However, there were others, including Christians of Pakistani origin who live in the United States and Britain, who called my husband and asked him to stop me from taking this initiative. Some of them dismissively said that I was setting up a church for ‘hijras’ [a derogatory slur for transgender people].”

Shafiq now says she is raising funds to construct a proper church building for the transgender community.

“I love reciting the Bible,” said Arzo, who only uses her first name. “Unfortunately, I had to suppress the urge for many years. Things are different now and I can pray to God without being mocked or judged by anyone.”