LONDON: Thirty years on, we continue to endure the catastrophic reverberations of the 1990 Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. This act set in motion events that would unleash a three-headed hydra of sectarianism, terrorism and Iranian militancy.

The August 2 invasion constituted an immense psychological shock. We woke to images of utter horror and chaos: Arab soldiers assaulting and looting another Arab nation. Ordinary Kuwaiti families upended from lives of luxury — fleeing as terrified refugees into Saudi Arabia. The invasion was particularly disconcerting, given that Kuwait had been a principal ally and backer for Baghdad during the previous decade’s war with Iran.

Julius Caesar’s crossing of the Rubicon famously marked his point of no return, committing his armies to a devastating and history-changing Roman civil war. The Kuwait invasion represented Saddam Hussein’s own personal Rubicon crossing.

ALSO READ: Moments that changed the Middle East

In 1990, Saddam was just another dictator who would have scarcely deserved a mention in the history books if he had been displaced in yet another Baathist, communist or Islamist coup a couple of years later. The Kuwait invasion saw him justifiably demonized in the global media as a savage, dictatorial monster who would have to be slain.

Within a year, hundreds of thousands of Iraqis would be dead — murdered by their own regime after the brutal suppression of uprisings which followed the Kuwait conflict. The Iraqi army was humiliated and destroyed, with tens of thousands of Iraqi soldiers dead, and many others fleeing home to join ill-fated uprisings leaving the skeletons of thousands of abandoned tanks scattered across the desert.

1990 Kuwait invasion recap

- On July 18 Iraq accuses Kuwait of stealing oil and encroaching on territory.

- Iraq’s President Saddam Hussein demands $2.4 billion from Kuwait.

- Kuwait accuses Iraq of trying to drill oil wells on its territory.

- Iraq accuses Kuwait of flooding oil market and driving down prices.

- On August 1 Arab League and Saudi Arabia suspend mediation attempts.

- On August 2 Radio Kuwait accuses Iraqi troops of occupying its territory.

- Faced with 100,000 Iraqi troops and 300 tanks, Kuwaiti army is overwhelmed.

- Kuwait City falls and Kuwait’s ruler Sheikh Jaber Al-Sabah flees to Saudi Arabia.

- UN Security Council demands immediate pullout of Iraqi forces from Kuwait.

- On August 6, Security Council slaps trade and military embargo on Iraq.

- President George H.W. Bush announces dispatch of troops to Saudi Arabia.

- On August 8, Iraq announces Kuwait’s “total and irreversible” incorporation.

- Later in the month, Iraq annexes Kuwait as its 19th province.

President George H.W. Bush made the equally fateful decision not to pursue Saddam’s army to Baghdad. The rights and wrongs of Bush’s decision continue to be argued over, but this left Saddam in power — wounded and vengeful. Unquestionably in 1990, Saddam had to be forced out of Kuwait, particularly as there were fears that he might send his forces deeper into the Gulf region. Yet cutting Saddam down to size led to a fundamental destabilization of the regional balance of power.

Throughout the 1980s, the ayatollahs’ regime in Tehran had been kept at bay by means of the vicious confrontation with Iraq, costing around a million lives. When Saddam’s regime fell like a dead branch in 2003, the Islamic Republic remained as a dominant regional force, free to spread its tentacles into Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Bahrain and beyond.

Already during the 1980s and 1990s, Tehran had been responsible for terrorist attacks, militant insurgencies and attempted coups, such as the 1996 Alkhobar bombings, which killed 19 US service personnel.

With Saddam gone, the ayatollahs desired not only to ensure that Iraq could never again exist as a threat, but to export their revolution throughout the Middle East, following the blueprint of Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Consequently, a sizable chunk of the region has been severed from the Arab sphere of influence, with Tehran today trying to knit these disparate nations together as a miserable and marginalized bloc of “resistance” states.

Opinion

This section contains relevant reference points, placed in (Opinion field)

Yes, Saddam was a monster — a murderous threat to his own people and his neighbors. But in the years since 1990 we have discovered that there are worse things than his kind of monster.

When the hateful regimes of Saddam, Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi, Syria’s Bashar Assad and Yemen’s Ali Abdullah Saleh were challenged and upended, the result was mass civil chaos which has cost upwards of a million lives, displacing countless millions. It may be more than a generation before these nations enjoy the most elementary levels of stability, if ever.

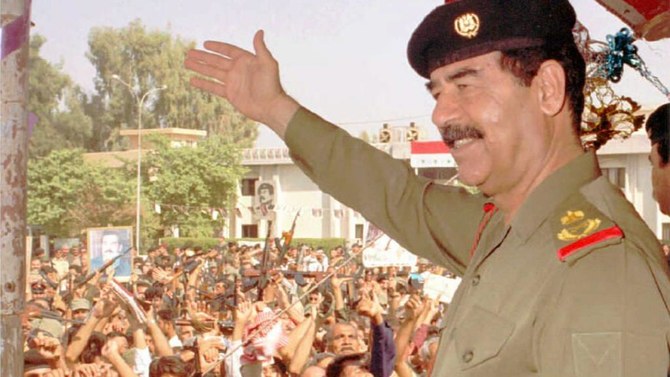

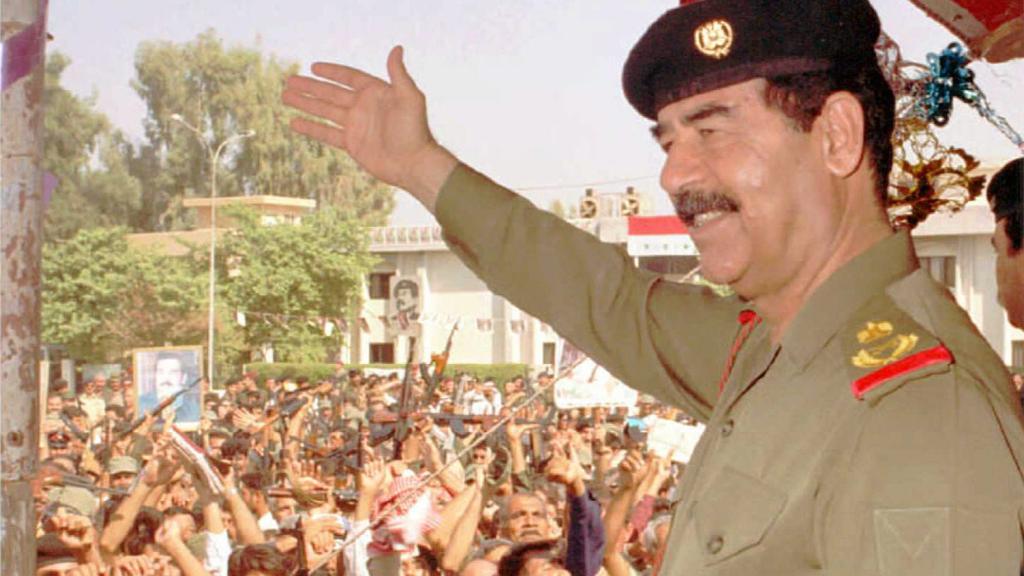

Former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein rallying his troops. (AFP photo)

I was an in-house analyst for CNN during the 2003 conflict. Anyone familiar with Iraq knew that regime change would be infinitely more challenging than President George W. Bush’s administration claimed. We shared Iraqis’ jubilation at the prospect of being rid of Saddam. Yet in our worst nightmares, few could have guessed how devastatingly far-reaching the ramifications of the invasion would be today, leaving Iraq and other nations as crippled, satellite dependencies of Tehran.

The events of 1990 and 2003 ignited the catastrophic Shia-Sunni divide, which in Iraq alone saw tens of thousands massacred in sectarian warfare as Iranian-sponsored militants bloodily erased Sunni and Christian populations from entire districts of Baghdad.

Saddam’s war helped radicalize figures like Osama bin Laden against the US, leading to Al-Qaeda and 9/11, which in turn set in motion the 2003 invasion, precipitating an explosive expansion of jihadist terrorism: Violence giving birth to violence on an ever-expanding scale.

Yes, Saddam was a monster, but in the years since 1990 we have discovered that there are infinitely worse things than monsters.

Baria Alamuddin

The White House in 2003 had neither the vision nor the desire to establish a stable, sovereign and well-governed Iraqi state. Through incompetence and malice, the US-led coalition succeeded in triggering a bloodbath, unifying Iraqis against them and handing over the keys of governance to Tehran. It all could have been so different.

During the 1980s, Saddam had been an ally of America and the West. These states conveniently turned a blind eye to his homicidal regime’s horrific crimes. Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait would change all that, while transforming himself from a necessary bulwark against Tehran to an international pariah. Overnight, he unified the entire world against him.

Today in 2020, there is plentiful evidence that Iran itself may be bringing the world to a tipping point where its terrorism, militancy and criminality become too horrific to ignore, with its suppression of the democratic aspirations of citizens throughout its “resistance bloc,” use of proxies to attack peace-loving nations, and efforts to acquire nuclear weapons to menace the world.

Just like Saddam, sabre-rattling ayatollahs risk their own Rubicon moment by taking their aggressive expansionism a step too far. And just like Saddam, the Iranian ayatollahs will eventually unite the world against them, bringing an unlamented end to their Satanic Republic.

_____________

• Baria Alamuddin is an award-winning journalist and broadcaster in the Middle East and the UK. She is editor of the Media Services Syndicate and has interviewed numerous heads of state.