QAMISHLI: Months after the territorial defeat of Daesh, Syria’s Kurds are pushing for an international tribunal to try alleged militants detained in their region.

The Kurds run an autonomous administration in the northeast of Syria, but it is not recognized by Damascus or the international community.

This brings complications for the legal footing of any justice mechanism on the Kurds’ territory, and the international cooperation required to establish one.

With Western nations largely reluctant to repatriate their nationals or judge them at home, could foreign Daesh suspects be put on trial in northeast Syria?

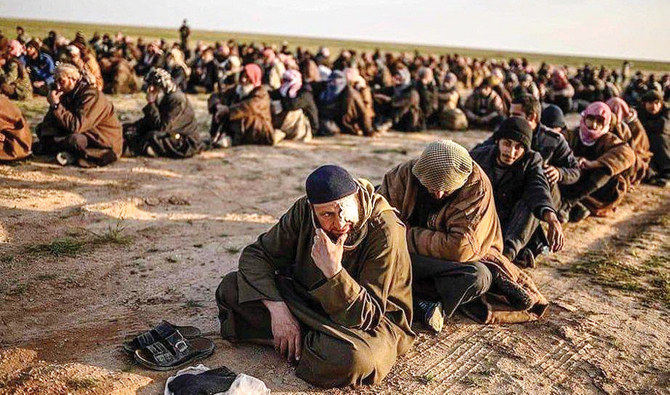

After years of fighting Daesh, Syria’s Kurds hold around 1,000 foreign men in jail, as well as some 12,000 non-Syrian women and children in overcrowded camps.

Almost four months after Kurdish-led forces backed by the US-led coalition seized Daesh’s last scrap of land in eastern Syria, few have been repatriated.

The Kurdish authorities say they are seriously exploring how to set up an international tribunal, and invited foreign experts to discuss the idea at a conference it hosted early this month.

“We will work to set up this tribunal here,” the region’s top foreign affairs official Abdelkarim Omar told AFP afterwards.

“The topic of discussion now is how we will set up this tribunal and what form it will take,” he said.

Daesh in 2014 declared a “caliphate” in large parts of Syria and neighboring Iraq, implementing its brutal rule on millions in an area the size of the UK.

The militants stand accused of a string of crimes including mass killings and rape, and a UN probe is investigating alleged war crimes.

Mahmoud Patel, a South African international law expert invited to the July conference, said any court should include input from victims and survivors.

It should be “established in the region where the offenses happened so that the people themselves can be part of that process,” he said, preferably in northeast Syria because the Kurds do not have the death penalty.

In Iraq, hundreds of people including foreigners have been condemned to death or life in prison.

In recent months, a Baghdad court has handed death sentences to 11 Frenchmen transferred from Syria to Iraq in speedy trials denounced by human rights groups.

Omar, the foreign affairs official, said he hoped for an international tribunal to try suspects “according to local laws after developing them to agree with international law.”

The Kurdish region has judges and courts, including one already trying Syrian Daesh suspects, but needs logistical and legal assistance, he said.

A tribunal would have “local judges and foreign judges, as well as international lawyers” to defend the accused, he said.

Nabil Boudi, a French lawyer representing four Frenchmen and several families held in Syria, said the Kurdish authorities seemed determined.

“They’re already starting to collect evidence,” he said after attending the conference.

“All the people who were detained and jailed had their own phone” and data can be retrieved from them, said the lawyer, who was however unable to see those he represents.

Boudi called for “a serious investigation by an independent examining magistrate ... that should take time and be far less expeditious than in Baghdad.”

Stephen Rapp, prosecutor in the trial of Liberian ex-president Charles Taylor, said the most realistic option to try foreigners in northeast Syria would be a Kurdish court.

It could have “international assistance conditioned on compliance with international law,” he said, including advice from a non-governmental organization specialized in working with non-state actors.