DUBAI: When a Queen in ancient Arabia wanted to impress kings, she would send them precious aromatic gifts, such as myrrh and frankincense — known as the earliest ‘Arabian oil.’

The ancient incense caravan route brought great wealth to Arabia as it passed from Yemeni kingdoms via Tayma — known as one of the oldest settlements in the province of Tabuk, Saudi Arabia — to the rest of the world from the 3rd millennium BCE to the first century CE.

From Bilqis, the Queen of Sheba, to tribal leaders, the great volume of incense, perfumes and spices traded during the last millennium BCE helped make the Arabian Peninsula an hub for trade between East and West.

The recently opened Perfume House at the Shindagha Museum in Dubai offers visitors a chance to experience these ancient fragrant cargos through custom-made devices and go on an aromatic journey to learn about the traditional making of perfumes, scented oils and incense, while exploring ingredients including saffron, Dihn Al Oud, roses from Damascus and Taif, and today’s synthetic materials.

“Perfume is an important part of Khaleeji and Arab culture. Every home has its own collection of perfumes and incense,” said Shatha Al-Mulla, head of the research and studies unit at the Architectural Heritage Department of Dubai Municipality, one of three entities that are working on the master plan of the Shindagha Museum.

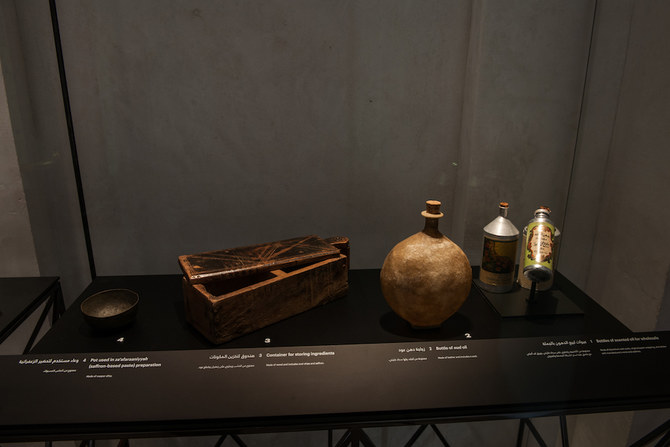

The Perfume House is located inside the former home of the late Sheikha Sheikha bint Saeed Al-Maktoum, who was an avid collector of perfume. Many of the artifacts were part of her personal collection, including perfume applicators and a rare 28-kilogram piece of oud, a raw scent ingredient and one of the most expensive objects on display, which she donated to the museum. There is even an ode to perfume, written by the late Sheikha herself

“Her knowledge of the art of perfume and its history is now preserved here for all generations to learn from,” said Al-Mulla.

Each of the five main halls has a different theme. In the first, visitors learn about the natural ingredients in Emirati and Gulf perfumes. For instance, a ‘tolah’ of oud oil, the size of a traditional oud bottle (11.67 ml), requires a total of 11.6 kg of agarwood.

“One of the things you learn here is the amount of effort and time it takes to make a single small bottle of perfume,” said Al-Mulla. “It is truly an art of balance, of creativity, and patience.”

The second hall is dedicated to the culture of perfume, from poetry to different styles of application. In the third ‘social uses’ room, one discovers how fragrances are used on textiles and in everyday life, such as stuffing cotton mattresses with small amounts of musk or saffron, while Mashmoom (basil variety) was placed inside pillows for a gentle calming scent.

The fourth hall reveals the ancient trade routes, along with details of archeological discoveries that highlight perfume’s historic importance.

The last hall offers video displays explaining how certain traditional perfumes are made.

“We each have a specific memory of different fragrances,” Al-Mulla concluded. “That’s why perfume remains a very personal ritual for each of us.”

THE LOWDOWN

WHERE: The Perfume House, Al-Shindagha Museum, Dubai

OPEN: Friday, 2.30 p.m. to 9 p.m.; daily except Tuesday from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.

ADMISSION: Adults AED15; Children AED10; Free for under-fives

WEBSITE: alshindagha.dubaiculture.gov.ae