CHRISTCHURCH: When Brenton Tarrant walked into Al-Noor mosque and opened fire, it was if a whole nation’s soul died.

“The worst of the world has visited our shores, and we’ll never be the same again,” New Zealand Foreign Minister Winston Peters said.

He spoke for New Zealand’s 4.9 million people, avowedly multicultural and welcoming.

There are about 60,000 Muslims in New Zealand, mostly ethnic Indians from Fiji, attracting little attention in a country of 200 ethnicities and 160 languages. Most of the victims of Friday’s terrorist attack were from Fiji’s islands, but there were also Afghans, and Muslims from Turkey and Somalia.

There was anger on social media that the attack appeared to have come as such a surprise to the security services. New Zealand police, who are not armed while on normal duty, had few details of how the attack was coordinated.

When Tarrant’s live video footage of his attack emerged on Facebook, authorities quickly —and mostly successfully — appealed to people not to share it on social media. New Zealanders quickly rejected a rambling, ranting manifesto posted by Tarrant. It was given little space and was mostly dismissed.

One prominent security analyst, Paul Buchanan, director of 36th Parallel Assessments, said the focus of New Zealand’s intelligence and security services had been on the threat from Islamist extremism, and limited resources meant they had neglected the threat from other sources.

Right-wing extremists have been visible and vocal in Christchurch recently. Terrible as Friday’s attack was, it was not surprising, Buchanan said, and Tarrant’s manifesto was “straight out of the white supremacist playbook.”

During the attack, police issued an urgent nationwide appeal to all Muslims to stay at home and to close all mosques. Armed police were posted quickly outside most city mosques.

Mulki Abdiwahab had been praying in a mosque with her mother when she heard gunshots. “I didn’t know what it was,” she said, “I’d never heard a gunshot, ever. I thought at first it must have been somebody banging on the window.

“My mum grabbed my hand and then we just we ran outside. Everyone was in chaos, just running for their lives. We just kept running, and running. The gunshots kept going on for about a good 10 minutes.”

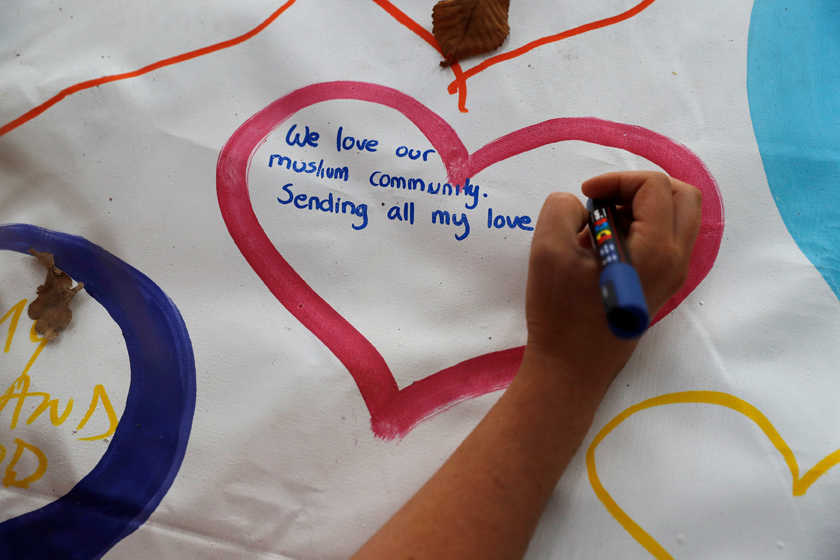

People write on a sign at a memorial as a tribute to victims of the mosque attacks, near a police line outside Masjid Al Noor in Christchurch, New Zealand, on March 16, 2019. (REUTERS/Jorge Silva)

Idris Khairuddin said prayers were just about to begin when he heard gunshots. His uncle Tamizi was one of six people he knew who was shot. “The gunshots sounded like pop, pop, pop,” he said. “I heard over 50.”

Carl Pomare, who had been driving past the mosque as the attack began, saw people running, and saw a five-year-old girl shot. “We looked at it thinking, we’ve got to get this little girl to the hospital now otherwise she’s going to die,” he said. “It was a pretty scary situation because there were still other shots being fired at the time inside the mosque.”

New Zealand legal procedures mean it is likely to be several days before the bodies of the victims are removed from the mosque. Identification is likely to take several days.

Friday’s terrorist attack was the worst in New Zealand history. The last was in 1985 when French secret agents blew up a ship in Auckland harbor, killing one person.

Christchurch has only recently recovered from a series of severe earthquakes, including one in 2011 that killed 187 people.