KABUL: The Afghan government on Monday rejected a new book that says Mullah Mohammad Omar, founder of the Afghan Taliban, lived within walking distance of United States bases in Afghanistan and never hid in Pakistan while a spokesman for the Afghan Taliban said the findings of the book were “correct.”

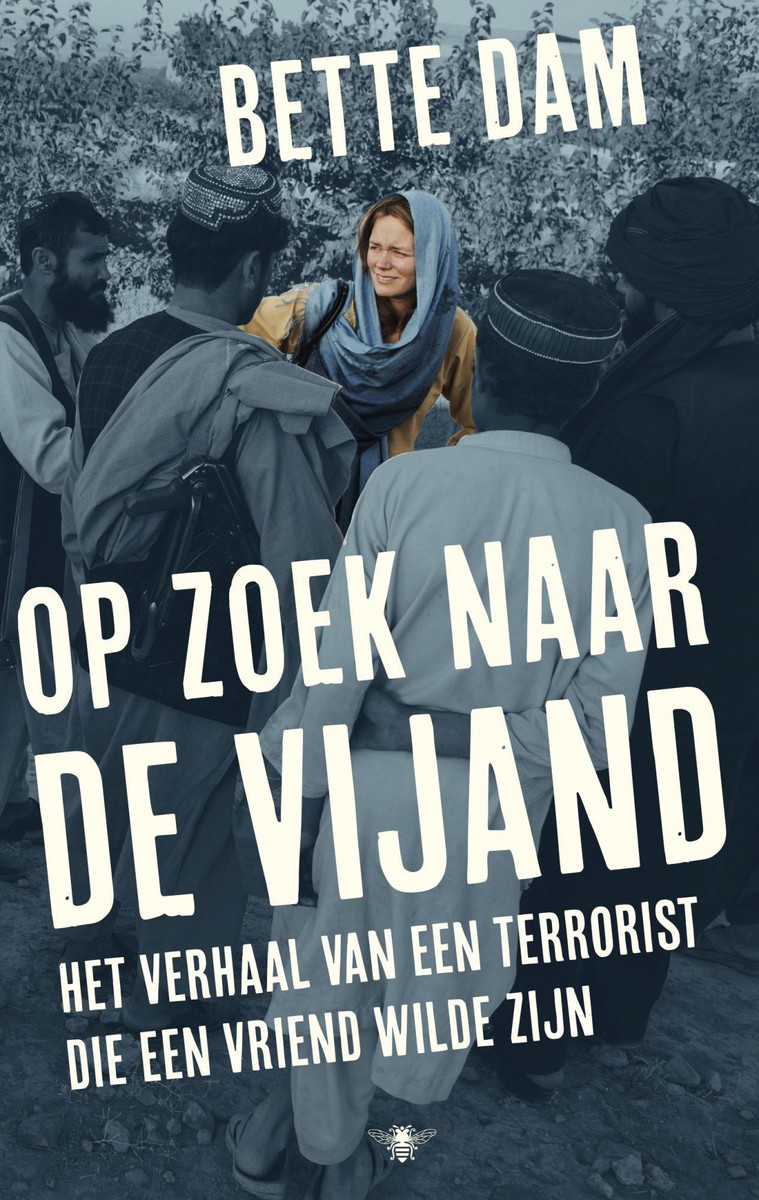

Dutch journalist Bette Dam spent five years researching her book “Searching for an Enemy” which was published in Dutch last month. This month, a summary of the findings were published in English by the newly launched Zomia think-tank.

In September 2015, Omar’s son had said in a statement that the insurgent leader had died of natural causes in Afghanistan.

The US State Department had a $10 million bounty on Omar’s head and the Taliban leader had not appeared in public since the American-led invasion of Afghanistan in 2001.

Haroon Chakhansuri, a spokesman for Afghan President Ashraf Ghani, rejected the findings of the new book.

“Not only we reject it, we see it as an effort to create and build an identify for the Taliban and their foreign backers,” Chakhansuri told Arab News. “There is sufficient evidence which shows he [Omar] lived and died in Pakistan.”

Zabiullah Mujahid, the spokesman for the Afghan Taliban, said in a Twitter post that Omar had spent his “entire time” in Afghanistan and “never visited #Pakistan or other country for a single day.”

“He passed away b/c [because] he refused treatment in another country for a curable disease,” Mujahid said. “Report published in this regard is correct,” he added, referring the new book.

Pakistan’s foreign office declined comment on the book but has always maintained in the years before his death that Mullah Omar was not hiding in Pakistan.

In her new book book, Dam details how the Taliban chief lived as a virtual hermit at a secret hideout, refusing visits from his family and filling notebooks with jottings in an imaginary language. Omar’s shelter was the home of Abdul Samad Ustaz, a former driver, who was then operating a taxi. On at least two occasions, Dam writes, US soldiers came within an inch of finding Omar, but failed to detect him.

The book, which coincides with a series of meetings between Taliban delegates and US diplomats in Doha on how to end the 17-year-long Afghan war, has drawn reactions from both ordinary Afghans and politicians.

Amrullah Saleh, known for having close ties with the CIA during the fall of the Taliban and who served for years as Afghanistan’s spy chief, called the report “inaccurate.”

“This is inaccurate. It is part of an effort to build an identity for the Taliban,” he said in a Twitter post. “I could give very hard evidence that he lived in Pakistan and died there,” he added, but did not present any additional details.

Saleh’s comments started a debate between him and Dam who asked him to provide the evidence, with Saleh said he would do at the right time.

According to Dam’s book, Omar spent his days listening to the BBC’s Pashto-language news service in the evenings, but rarely commented on news of the outside world, not even when he learned about the death of Bin Laden, the man whose attack on the US led to the end of Taliban rule.

Dam wrote about one instance in which a patrol approached as Omar and Omari were in the courtyard of the shelter. Alarmed, they ducked behind a wood pile, but the soldiers passed without entering.

A second time, US troops entered and searched the house but did not uncover the concealed entrance to the secret room. It was not clear if the search was the result of a routine patrol or a tip-off.

The report “will boost Taliban’s image and they can argue that they are not backed by Pakistan and that their leader, despite America’s sophisticated surveillance and technology lived near America’s base in Afghanistan’s soil,” Ahmad Saeedi, a former Afghan diplomat, told Arab News.