KARACHI: The daughters of a Pakistani man considered a hero in both his home country and Saudi Arabia for his rescue of 14 people during torrential floods in Jeddah say he “will always be alive in our memory.”

In late November 2009, as flash floods roared through the port city, Farman Ali Khan secured a rope to his waist and jumped into the roaring floodwaters to rescue people.

Khan saved 14 lives, but lost his own while attempting to rescue a 15th person.

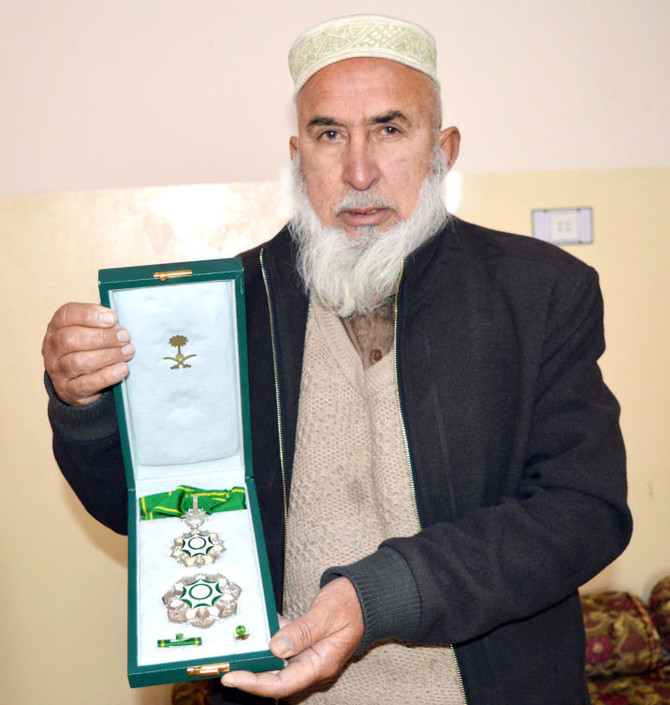

He was posthumously awarded the King Abdul Aziz Medal of the First Order by the Saudi government and Pakistan’s Tamgha-e-Shujat by then President Asif Ali Zardari.

Khan’s three daughters, Zubaida, Madeeha and Javeriah, told Arab News by phone from his hometown of Swat this week that they remembered their father as a patient, mild-mannered family man who loved to joke and lived to help others.

“He always dreamt of being a doctor, but financial troubles forced him to stop his education and become a grocer in Jeddah,” said Zubaida. “He couldn’t become a doctor, so now we will fulfil his dream,” she said.

“We unluckily spent little time with our father,” she said. “But he will be alive in our memories forever. Everyone in our neighborhood and school knows us as the children of a hero. Khan is our superstar.”

Khan’s father, Umar Rehman, told Arab News his son was one of nine siblings, and was hardworking and always busy. “But he would call his family in Pakistan every chance he got.”

“He was brave and fearless, but very kind and obedient,” Rehman said. “He would always talk in a light way, laughing out loud. I remember that when his grandmother would get upset, he would crack jokes until she started laughing. I never saw him angry or arguing with anyone.”

Rehman said he was devastated when he heard about his son’s death, but the story of his bravery “started healing my wounds, gradually.”

Shortly after Khan’s death, the family received a condolence letter from Saudi King Abdullah and accepted an invitation to visit the Kingdom as special state guests. A grand reception was held at the palace where the king awarded Khan the King Abdul Aziz Medal of the First Order.

His father said that just weeks before his death, Khan had planned to get him a longer-term Hajj visa so they could spend time together.

“Farman from his childhood had learned to live for others. He gave us the message that those living for others live long, even if their souls journey to another world.

“Farman is alive, in our hearts and in our memories,” Rehman said.