DUBAI: The Egyptian director and actor Youssef Chahine is often cited as one of the Arab world’s greatest filmmakers. As part of the Sharjah Film Platform this month, three of his films were selected to be screened twice each as the start of what artist, blogger and film programmer Hind Mezaina hopes will be a long-term retrospective of the late director’s work.

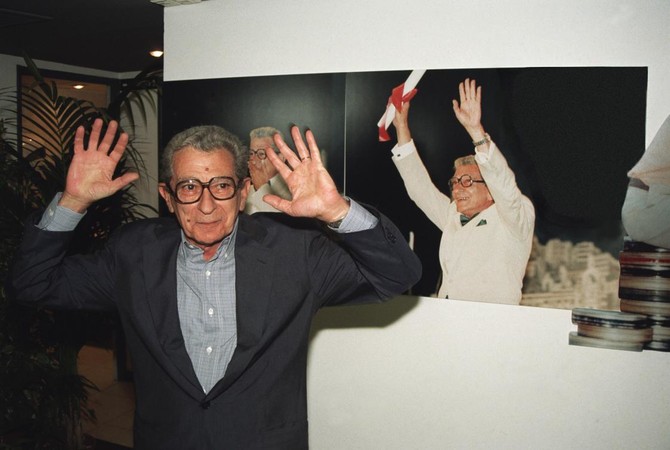

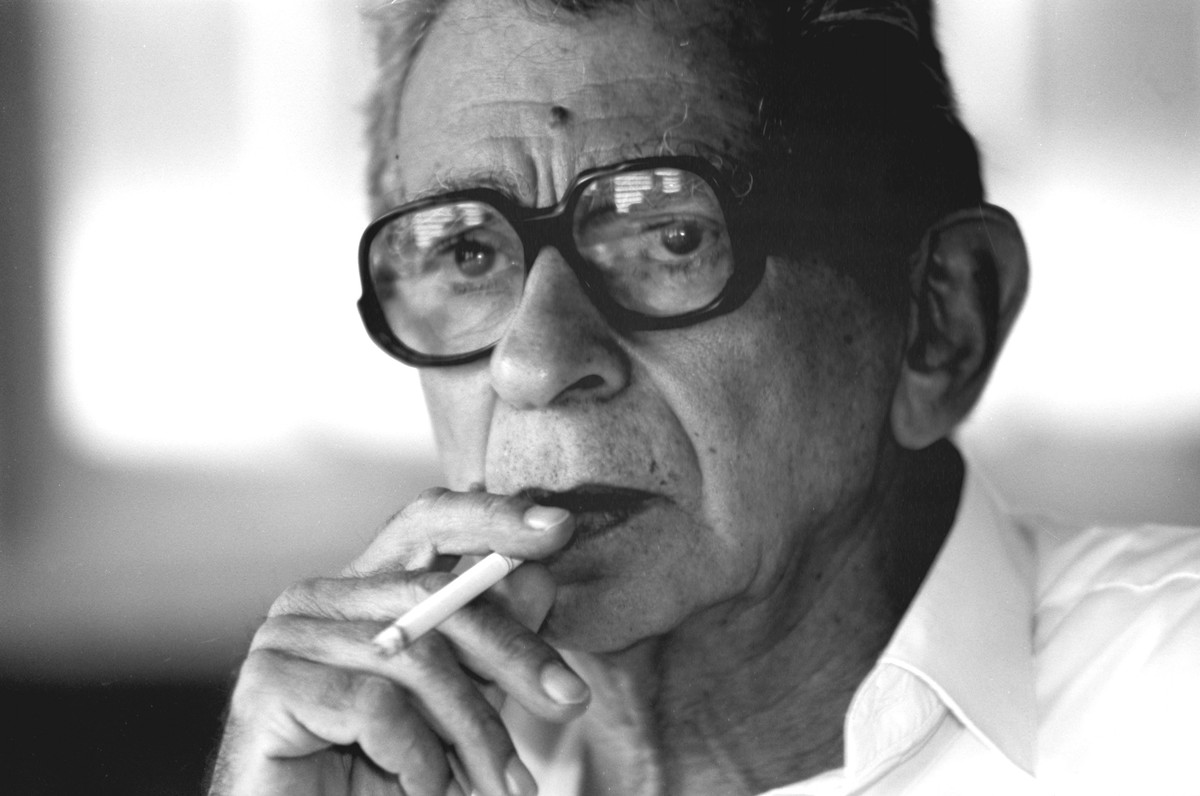

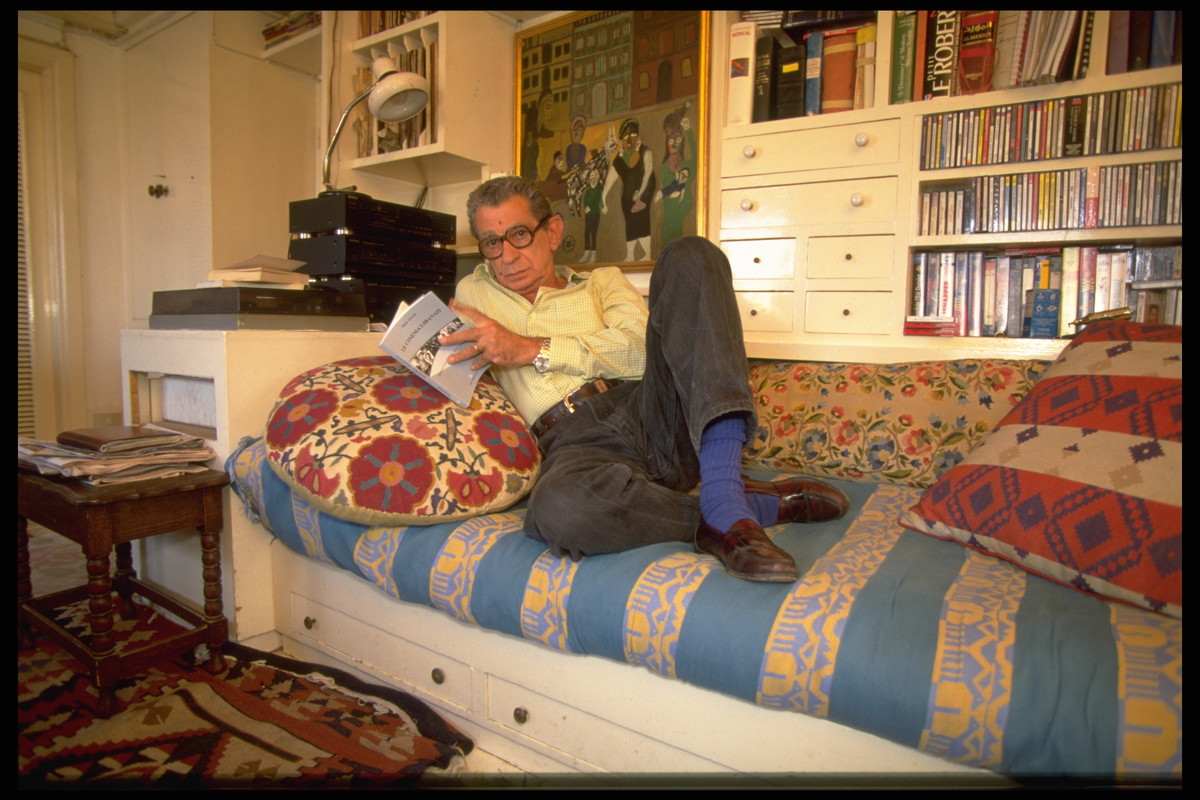

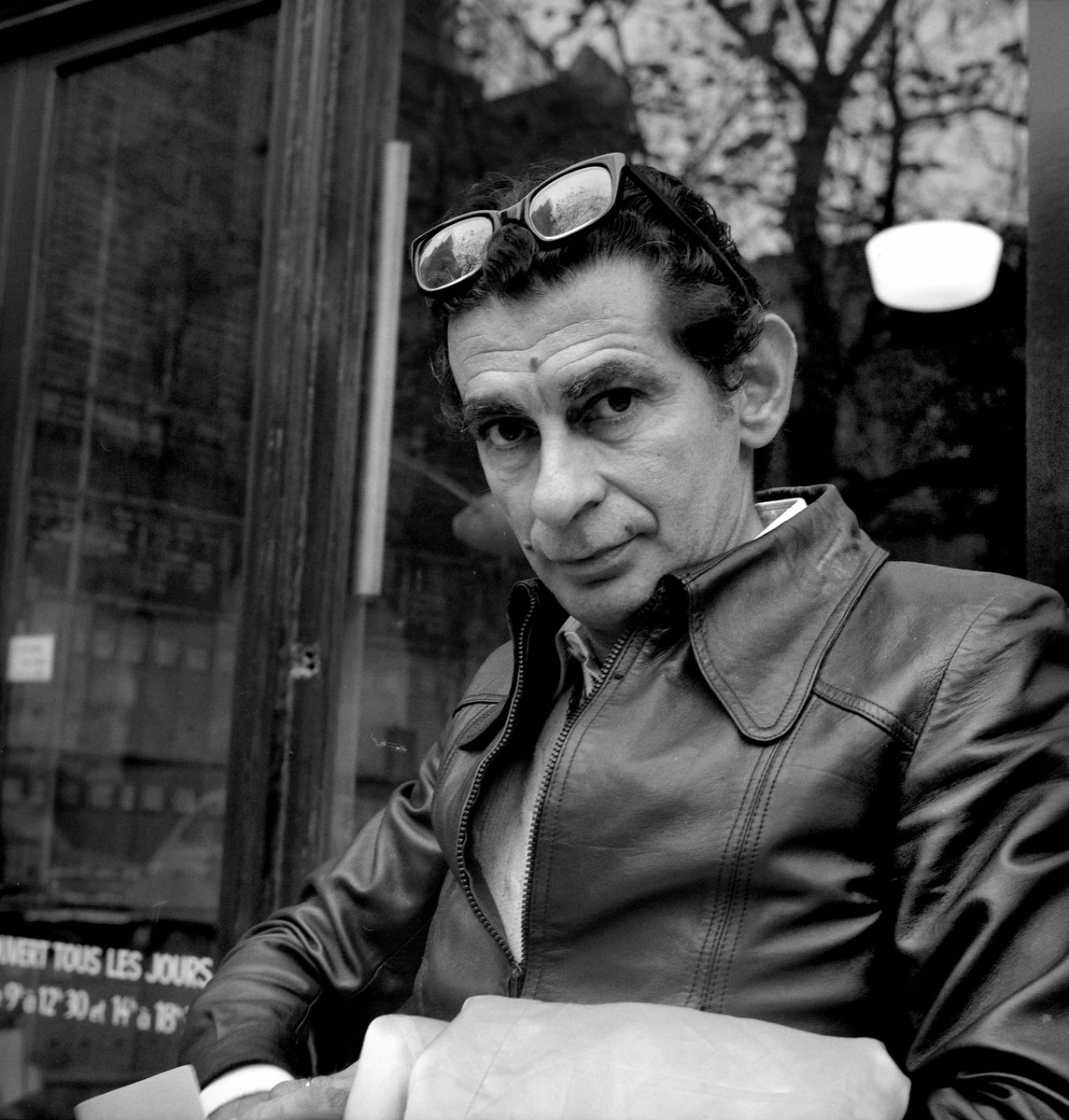

Youssef Chahine. (Getty Images)

Chahine’s long career, which spanned six decades until his death in 2008 at the age of 82, was characterized by controversy. Many of his films were initially banned in his homeland and the wider region, and it took many years before his work earned the recognition it deserved in the Middle East. Instead, he was embraced by international festivals and film critics, particularly in France (Chahine was honored with a lifetime achievement award at Cannes in 1997).

Opinion is divided on just how skilled a filmmaker Chahine was. “I don’t think he’s the best, technically,” Mezaina told Arab News. “Some films I’ve found really great, and some I found really frustrating to watch. They’re a mixed bag.” Her opinion has been echoed by many critics.

However, Chahine is almost universally acclaimed for his courage as a storyteller. His films invariably had a socio-political point to make at a time when few Arab filmmakers were challenging the status quo.

“A lot of his films were banned, or seen as problematic,” Mezaina said. “His films have these constant themes of power, oppression, corruption and nationalism. Religious fundamentalism also started coming in. And there’s a strong theme of sexuality in the second half of his career too. So it’s a troubled history. But he always (pressed) ahead and made his films.”

While Chahine focused primarily on Egyptian society, he touched on themes that were applicable to the wider Middle East and, indeed, the world.

His love for old-school Hollywood studio films, for example — bolstered by the time he spent studying film at the Pasadena Playhouse in the mid-Forties — gave way in later years to despair at how the US film industry — and foreign policy — had developed. And he was always unapologetic about highlighting the concerns of the Egyptian people.

“You can’t be an artist if you don’t know the social, the political, and the economic context,” Chahine told German website Qantara in 2006. “If you talk about the Egyptian people, you must know about their problems. Either you are with modernity or you don’t know what the hell you’re doing. Because when Mr. Bush farts we jump.

“I still like the American culture,” he continued. “They are very inventive, they always do new things. But the basic philosophy of a very, very savage capitalism makes them very violent. The films prove to what extent they have become violent.”

His willingness to speak openly about such topics — and to put them front and center in his movies — is what makes Chahine such a significant figure in Arab cinema, Mezaina believes.

“I think it’s more about his ideas and his stories (than his technique),” she said. “He was Christian, from Alexandria, so growing up he was exposed to very cosmopolitan surroundings. You see that in his films, but he’s very casual about it — there are characters from different religions and backgrounds, but he’s not doing that to make a big statement; it’s just a reflection of what he grew up with and kind of a showcase of what (he saw as) normal.

“I think a lot of artists who (are seen as controversial) are doing it out of love, not deliberately trying to be ostracized because they’re being critical. It’s an attempt to showcase things to help improve them. He always said he made his films for Egypt. Over time you can see he’s venting his frustration with the politics in the region and within his country, and that comes across in his films. Even in the early Fifties, when it was a monarchy in Egypt, he’s still dealing with themes of power and how people are oppressed. That’s always a strong theme in his films: The helpless and the rich.”

That’s clear in two of the films screened in Sharjah over the past week: “Cairo Station” — the 1958 film which first brought Chahine international recognition — and 1969’s “The Land.”

In the latter, a group of poor farmers fight to save their plots from the development plans of the local upper-class. “It’s set during the monarchy, in the Thirties, but it’s definitely talking about the state of politics in the Fifties and Sixties,” Mezaina explained. “It’s a film, really, about a mentality of disappointment with the state and with its leaders, and it’s also a very strong comment on masculinity — this idea of ‘What are you if you don’t own your land, or fight for your land?’ It’s very grim, but to me it’s a very powerful, and very important, film.”

In the black-and-white “Cairo Station,” which takes place over 24 hours in Cairo’s main train station, Chahine stars as anti-hero Kenawi, a sexually frustrated newspaper salesman obsessed with fellow street-vendor Hanouma. It’s an excellent portrayal of the chaos and energy of Cairo itself.

“It’s fast, and it showcases all slices of life,” Mezaina said. “We’re exposed to the poor; the bourgeois; the union man; religious men; women who are hustling to make money; feminists. It’s a really fascinating film, to cover so many scenes in under 80 minutes, and done really well. It’s a huge achievement.”

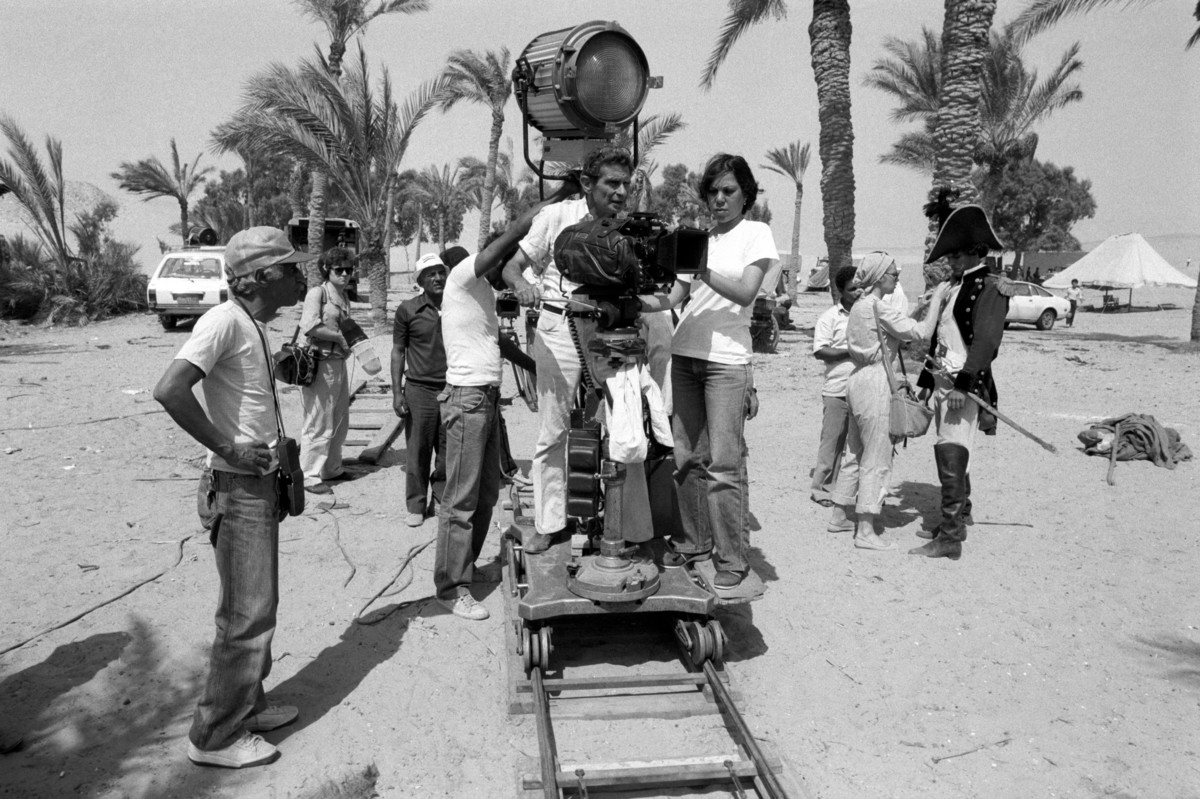

The third film Mezaina chose to screen at Sharjah Film Platform was “The Sixth Day” from 1986. “I selected it because of the musical element. Chahine was fascinated by musicals, and his way of approaching them was really quite interesting. It’s his tribute to old-school Hollywood musicals, but with an Egyptian budget,” she said with a laugh. “It’s set during the Egyptian cholera epidemic in 1947. The sixth day was the turning point; if you survived the sixth day, you were going to recover.”

The film stars the French diva Dalida, born in Egypt to Italian parents and winner of the Miss Egypt title in 1954. Contrary as ever, Chahine did not give this glamorous international star a singing role, instead casting her as a distinctly unglamorous peasant trying to protect her son, who is infected, and hide him so that he isn’t taken away to die.

“He was always very brave in terms of casting,” Mezaina said. “A lot of his films featured unknown actors. He’s the one who discovered Omar Sharif, for example. And a lot of actors would appear in a lot of his films, these people who started out with him with no experience. He had people who were dedicated to him and would say yes to whatever he did.”

Clearly, Chahine wielded great influence, and did so for a remarkably long time, just as he retained his ‘enfant terrible’ spirit even as an old man.

Some of his films, Mezaina suggested, might be dismissed because of their low budget — which means the scenery, costumes and special effects (with which Chahine experimented when he could) are sometimes less than convincing.

“But if you pause and try and understand the context of when the film was made, and for how much, and why,” she said, “that’s when I think his films lead to very rich discussions of ideas and opinions.”

It’s that ability to spark conversation through his work that Mezaina sees as perhaps Chahine’s greatest legacy.

“The idea with Sharjah is really to dig deeper into his films and have those discussions,” she continued. “I feel the discussions — in some cases anyway — are often more interesting than the films themselves.”