LONDON: The US military on Saturday insisted its missile strikes against three targets in Syria had dealt a “severe blow” to Bashar Al-Assad’s ability to produce chemical weapons.

American cruise missiles flattened a research center on the edge of Damascus and destroyed another site used as a command center and storage facility in the Syrian capital. French and British jets destroyed a facility near Homs and another at Shayrat.

The strikes significantly limited Assad’s ability to produce chemical weapons, Lt. Gen. Kenneth McKenzie, director of the US military’s Joint Staff said, adding it would set back the regime’s ability to produce such weapons “for years.”

His confidence in the success of the mission and the assertion that the targets were the “heart” of the Syrian chemical weapons program, raised a broader question that goes to the core of the failure of Western policy on the conflict: How has the Syrian president been allowed to get away with repeatedly using poisoned gas on his own people?

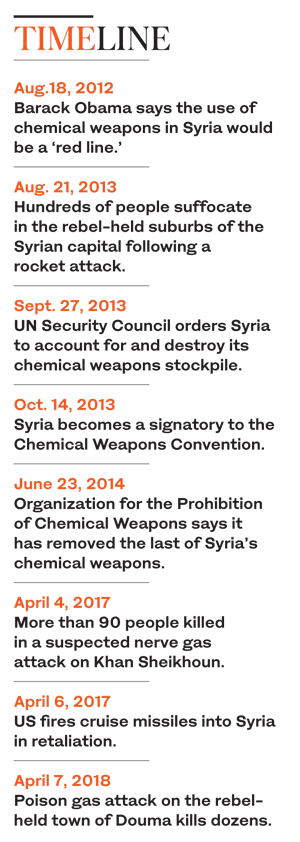

Barack Obama first set his “red line” on the use of chemical weapons in 2012. When that line was crossed in August 2013, a doomed attempt was launched by UN experts to rid the country of Al-Assad’s chemical weapons stockpiles.

The futility of that exercise was fully exposed when dozens more died from symptoms similar to that caused by sarin, after an air raid on Khan Sheikhoun in Idlib province last year. Keen to act decisively in the way his predecessor had failed, Donald Trump ordered missile strikes on an airbase that were little more than a rap on the knuckles for the Syrian government.

Stockpiles

The ineffective policies of the two administrations were highlighted again in Douma last week with the all-too-familiar images of Syrian infants gasping for breath. Assad stands accused of the third major chemical weapons attack unleashed during the seven-year conflict, and countless reports of lower-level use of chemicals against civilians.

The Pentagon said yesterday that the missile strikes last year that damaged aircraft, hangars, and runways at the Shayrat airbase had targeted the “means of delivery”, while this time around they had gone after the main facilities of the program.

“I would say there is still a residual element of the Syrian program that’s out there,” McKenzie said. “I’m not going to say that they’re going to be unable to continue to conduct a chemical attack in the future. I suspect, however, they’ll think long and hard about it.”

Karl Dewey, an expert on chemical, biological and nuclear assessments at defense Jane’s by IHS Markit, said it remained to be seen if the strikes would deter the future use of chemical weapons.

“The US strike last April did not provide a consistent response to the on-going allegations and failed to deter chemical attacks,” he said.

Syria began stockpiling chemical weapons in the early 1970s, according to US assessments. With the help of the Soviet Union, Damascus started to gather the knowledge and materials to develop its own weapons in the 1980s.

Before the uprising against Al-Assad in 2011, the Syrian Scientific Studies and Research Centre was believed to operate at least four manufacturing plants for chemical agents, and dozens of storage facilities were built across the country.

Rocket attack

In 2012, Israel accused Syria of having one of the world’s largest chemical weapons stockpiles, including sulfur, mustard, sarin and VX nerve agents.

A French military assessment from 2013 said Assad had a vast array of weapons systems that could deliver the chemicals. The section of the military responsible was the highly loyal “Branch 450” from the same Allawite religion as the president.

Syria’s horrifying capability was realized in August 2013, when an opposition-held area on the edge of Damascus was struck by rockets containing sarin. More than 1,000 people are estimated to have died in the strike on Eastern Ghouta. The US and other countries said they were certain the attack was carried out by Assad’s forces.

The red line set by Barack Obama had been crossed, but instead of a military response, a US-Russian agreement was signed to destroy the Syrian regime’s chemical weapons.

Assad’s government was forced to join the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW).

A year after the Eastern Ghouta attack, the White House declared that 581 tons of sarin and 19.8 tons of mustard gas had been destroyed under the OPCW’s supervision.

For the Syrian civilians still suffering the horrors of attacks using chemical weapons, it clearly wasn’t enough.