LONDON: Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman will arrive in the US this week for high-level meetings with President Donald Trump. But before he visits the White House, the Saudi heir will introduce himself to the American public.

On Sunday, the CBS television network will air an interview with the crown prince on its flagship “60 Minutes” current affairs program, and for his first-ever interview with a US broadcaster, no subject was off limits.

“There were no time restrictions and no preconditions,” Norah O’Donnell, the CBS anchorwoman who interviewed the crown prince in Riyadh, told Arab News.

“It seemed to me that there was a desire to show the American public what he believes, to show that Saudi Arabia is changing. The crown prince wants the US audience to understand him.”

The interview is wide-ranging and remarkably candid, with topics including the war in Yemen and the anti-corruption investigation launched last year at the prince’s behest, which resulted in high-ranking businessmen and officials being detained.

“For the first time, the crown prince tells in his own words what happened at the Ritz-Carlton. He speaks forcefully about Iran and about the role of women in Saudi society. He also talks about how Islam has been misinterpreted by extremists, whether it has to do with women’s rights or education or larger cultural traditions,” said O’Donnell.

“I think some of that may be newsworthy,” she said.

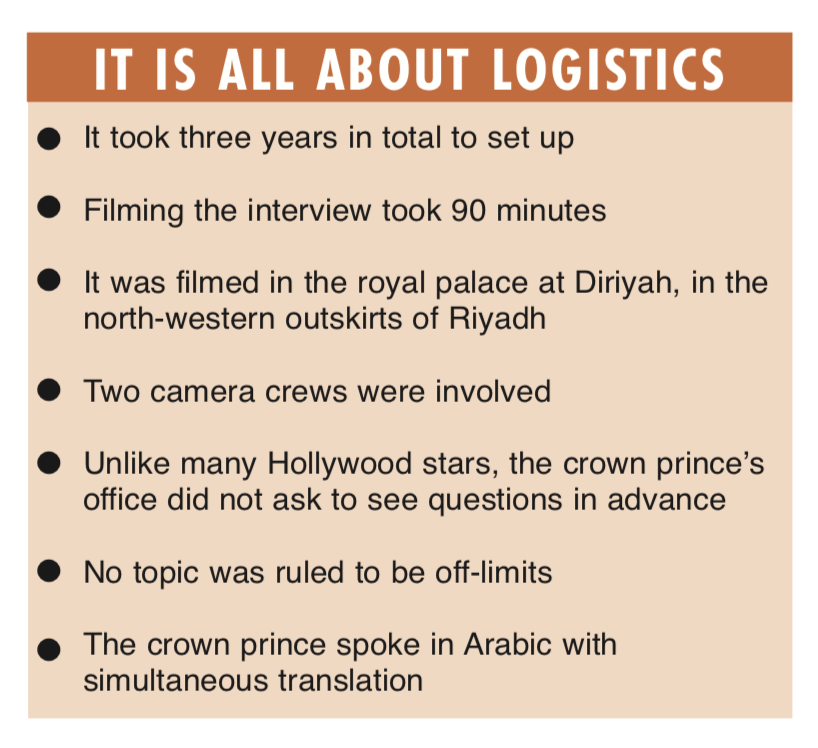

Bringing the interview to fruition took three years of negotiations. O’Donnell said that in April 2015 she started hearing that King Salman, who had just assumed the Saudi throne, was someone to watch, and she persuaded “60 Minutes” that gaining an interview with the Saudi leadership was an idea worth pursuing.

She first met Prince Mohammed bin Salman — then still deputy crown prince — at the Saudi ambassador’s residence in Washington in June 2016.

“It was his first visit to Washington. I asked about Vision 2030 and made my pitch for an interview to him in person. He was familiar with ‘60 Minutes’ and we explained that the interview would not just involve meeting in a hotel for 20 minutes. We wanted to come to Riyadh and have unprecedented access to the royal palace. We wanted to know how he spends his weekends and to show him to people.”

The meetings and conversations continued. “We had confidence that we were going to get the interview but no assurance,” said O’Donnell.

The anchorwoman and her production team were finally given the green light a month ago. They also got everything else they wanted: The Saudis neither requested questions in advance nor vetoed any topic of discussion.

“Their attitude was, ‘We have nothing to hide,’” said O’Donnell. “It was extraordinary.”

The formal 90-minute interview was conducted two weeks ago in the royal compound in Diriyah, on the northwestern outskirts of Riyadh, shortly before the crown prince left for his visit to Britain.

He chose to speak in Arabic, with simultaneous translation for the American crew.

“Most of the ministers in Saudi Arabia have been educated in the US or England, and there are currently 150,000 Saudis studying in the US, but one of the surprising things about the crown prince is that he is entirely Saudi-educated,” said O’Donnell. “He explained that his father, King Salman, wanted all of them (his children) to attend universities in Saudi Arabia because your time as a student is really formative. I thought that was really interesting.

“In the interview, you see that the crown prince does speak English when we’re meeting in his office, when it’s more casual. But when talking about business and policy, where you want to be very precise, it’s not that surprising that he would want to speak in Arabic.”

And precision was certainly called for in the face of tough questioning on Yemen and Iran. The crown prince was clear that as soon as Iran acquired nuclear weapons, Saudi Arabia would follow suit.

“He did not flinch from any questions,” she said.

The encounter was also a first for O’Donnell. The seasoned journalist has covered American politics for 20 years through the administrations of three presidents. Her father served in the First Gulf War and she has long been fascinated by the Middle East. Yet she had never been to Saudi Arabia. What preconceptions did she — and by extension, the American people — have about the country?

“I wouldn’t want to speak for 300 million Americans, but for most, Saudi Arabia is a world away. The general perception of Saudi Arabia is oil and wealth. But Saudi Arabia is also America’s oldest ally in the Middle East, and President Trump chose the country for his first foreign trip as president. Saudi Arabia matters.”

She also met Saudi women at Princess Nora University in Riyadh.

“The women I spoke to told me that the two biggest issues for them were driving and child care. One woman said lifting the driving ban meant that she would be able to get to work on time. She is about to become a surgeon.

“But in lifting the ban, the Saudis are not just saying, ‘OK, you can all go out and get driving licenses now.’ They’re not doing that. Instead, they have set up driving schools in universities and 70,000 women have signed up for those classes. They teach them about safety. And they even have day care.

“It was extraordinary to me because any country can just say, ‘You have these rights,’ but in Saudi Arabia they are actually providing schools to teach women about safety. For a country that has been well behind the curve, they at least appear to be trying to get it right.”

O’Donnell says she also saw how the power of the religious police has been curbed — again by royal decree.

“We did have an encounter with them when they shouted at one of our producers and that was scary. But we also knew that they could not do any more than that.”

Though no dress restrictions were imposed, O’Donnell chose to wear an abaya in public while in Riyadh.

“It felt more comfortable because everyone else was wearing abayas. After all, when the crown prince met Mark Zuckerberg during that trip in 2016, he wore a blazer and jeans.”

And what were her impressions of the young man who is transforming his country?

“He appears quite mature beyond his years, extremely confident, thoughtful and incredibly forthright in his answers. He is ambitious for his country. The fact that he has been elevated within the family at such a young age shows he enjoys the trust of his father, whom he briefs after every meeting.

“He wants to show that Saudi Arabia is changing. There is a desire to show what he believes and what his vision is. We were all fascinated by this young man who is in such a hurry to enact change. The pace of that change is remarkable. He has also been called reckless and bold, and there is no disputing that he has enormous power — unchecked power. But he is a man who believes in openness, who needs to communicate. He doesn’t want to be misunderstood.”