NEW YORK: Facebook is forging ahead with its messaging app for kids, despite child experts who have pressed the company to shut it down and others who question Facebook’s financial support of some advisers who approved of the app.

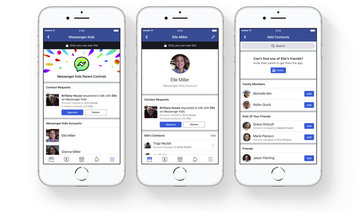

Messenger Kids lets kids under 13 chat with friends and family. It displays no ads and lets parents approve who their children message. But critics say it serves to lure kids into harmful social media use and to hook young people on Facebook as it tries to compete with Snapchat or its own Instagram app. They say kids shouldn’t be on such apps at all — although they often are.

“It is disturbing that Facebook, in the face of widespread concern, is aggressively marketing Messenger Kids to even more children,” the Campaign For a Commercial-Free Childhood said in a statement this week.

Messenger Kids launched on iOS to lukewarm reception in December. It arrived on Amazon devices in January and on Android Wednesday. Throughout, Facebook has touted a team of advisers, academics and families who helped shape the app in the year before it launched.

But a Wired report this week pointed out that more than half of this safety advisory board had financial ties to the company. Facebook confirmed this and said it hasn’t hidden donations to these individuals and groups — although it hasn’t publicized them, either.

Facebook’s donations to groups like the National PTA (the official name for the Parent Teacher Association) typically covered logistics costs or sponsored activities like anti-bullying programs or events such as parent roundtables. One advisory group, the Family Online Safety Institute, has a Facebook executive on its board, along with execs from Disney, Comcast and Google.

“We sometimes provide funding to cover programmatic or logistics expenses, to make sure our work together can have the most impact,” Facebook said in a statement, adding that many of the organizations and people who advised on Messenger Kids do not receive financial support of any kind.

But for a company under pressure from many sides — Congress, regulators, advocates for online privacy and mental health — even the appearance of impropriety can hurt. Facebook didn’t invite prominent critics, such as the nonprofit Common Sense Media, to advise it on Messenger Kids until the process was nearly over. Facebook would not comment publicly on why it didn’t include Common Sense earlier in the process.

“Because they know we opposed their position,” said James Steyer, the CEO of Common Sense. The group’s stance is that Facebook never should have released a product aimed at kids. “They know very well our positon with Messenger Kids.”

A few weeks after Messenger Kids launched, nearly 100 outside experts banded together to urge Facebook to shut down the app , which it has not done. The company says it is “committed to building better products for families, including Messenger Kids. That means listening to parents and experts, including our critics.”

One of Facebook’s experts contested the notion that company advisers were in Facebook’s pocket. Lewis Bernstein, now a paid Facebook consultant who worked for Sesame Workshop (the nonprofit behind Sesame Street) in various capacities over three decades, said the Wired article “unfairly” accused him and his colleagues for accepting travel expenses to Facebook seminars. He said he did not work for Facebook as a consultant at the time he was advising it on Messenger Kids.

Bernstein, who doesn’t see technology as “inherently dangerous,” suggested that Facebook critics like Common Sense are also tainted by accepting $50 million in donated air time for a campaign warning about the dangers of technology addiction. Among those air-time donors are Comcast and AT&T’s DirecTV.

But Common Sense spokeswoman Corbie Kiernan called that figure a “misrepresentation” that got picked up by news outlets. She said Common Sense has public service announcement commitments “from partners such as Comcast and DirectTV” that has been valued at $50 million, which the group has used in other campaigns in addition to its current “Truth About Tech” effort.

Facebook forges ahead with kids app despite expert criticism

Facebook forges ahead with kids app despite expert criticism

How media reshapes the rules of diplomacy

- International envoys discuss influence diplomacy, misinformation, and the growing need for credible storytelling

- Dya-Eddine Said Bamakhrama: The Saudi Media Forum itself is a tool of influence diplomacy, projecting the Kingdom’s image and soft power to the world

RIYADH: As dialogue surrounding the media’s influence across all sectors continues at the fifth edition of the Saudi Media Forum, some of the Kingdom’s ambassadors took to the stage to discuss diplomacy in an age of greater transparency.

A major topic on the panelists’ minds was “influence diplomacy,” an evolution of traditional diplomacy shaped by modern realities, said Ambassador of Djibouti to the Kingdom and Dean of the Diplomatic Corps Dya-Eddine Said Bamakhrama.

Influence diplomacy draws on soft power, he said. It uses tools such as arts and culture, sports, education, and humanitarian work to serve political interests and enhance credibility.

According to Bamakhrama, Saudi Arabia harnesses that influence through international forums, cultural initiatives, and a growing global sports presence.

“The Saudi Media Forum itself is a tool of influence diplomacy, projecting the Kingdom’s image and soft power to the world,” he said. “When a child in Africa or Latin America wears the jersey of a Saudi football club, that is influence diplomacy reaching far beyond borders.”

South African Ambassador to the Kingdom Mogobo David Magabe added that every country seeks to project an image that accurately reflects its culture, values, and identity to the world through food, music, cinema, civil society engagement, and cultural exchange.

However, Magabe warned that influence diplomacy must respect legal frameworks, avoid interfering in internal affairs, and operate transparently and ethically.

Spain’s Ambassador to the Kingdom Javier Carbajosa Sanchez echoed those remarks in saying that influence diplomacy can be a positive tool when it is ethical, disciplined, and grounded in facts.

Media has historically played a generally positive role in shaping public opinion, he said. But the rise of digital platforms requires a more responsible hand.

Diplomatic communication must follow rules, training, and ethical limits. “Propaganda may work temporarily, but credibility is what endures,” Sanchez said.

The ambassadors also highlighted that media today, particularly digital media, was a key actor in diplomacy, not just an observer.

While credibility depends on truthful and consistent narratives, digital platforms also enable the rapid spread — and exposure — of falsehoods.

“In today’s connected world, lies are exposed faster than ever,” Bamakhrama added.

Propaganda-based diplomacy no longer survives in the age of digital transparency. Instead, an effective diplomatic narrative relies on diplomats and policymakers’ understanding of the audience’s mindset, honest and clear communication of facts, and giving the necessary context for events.

Truth, he said, does not always require full disclosure, but it does not tolerate deception.

And the truth is especially paramount during times of crisis. The ambassadors agreed that false narratives collapse during conflict, and unchecked narratives can escalate crises beyond control.

“During conflict, responsibility must be shared between governments and media institutions,” Sanchez said.

Misinformation, the speed of news cycles, and the pressure to respond instantly were cited by the South African ambassador as the biggest challenges facing influence diplomacy today.

Accurate storytelling weighed heavily on speakers’ minds in the forum, especially in an era when messages can diverge between digital and traditional media.

Many of the same concerns surfaced in “Television and Streaming Platforms: Conflict or Opportunity?”, a panel focused on journalism and broadcasting, where media leaders examined how misinformation and competition are reshaping television.

Tareq Al-Ibrahim, director of MBC 1 and MBC Drama Channels and chief content officer at MBC Shahid platform, said that social media is both a bridge and competitor to television.

“It allows us to reach wider and more diverse audiences, but it also competes for people’s time,” he said.

In addition to audiences being larger, more fragmented, and more demanding, news organizations must now not only compete with other newsrooms, but with every other form of content on social platforms.

Despite this, professional journalism still holds great value and reaches wide audiences — if it adapts.

Al-Ibrahim added that competition was essential, not just for platforms, but for the entire value chain: “From writers to cameramen to directors, competition raises everyone’s standards.”

He also pointed to the evolution of Arabic content over the last decade as driven by competition from Netflix, Shahid, and other regional and global platforms.

Amjad Samhan, head of social media at Al Arabiya news network, described what the network’s transition was like from television to social media.

The challenge, he said, was figuring out how to deliver news to people who are not actively looking for news.

One solution was to transform long-form TV content into fast, digital formats. “We built a parallel digital newsroom with the same standards and principles,” Samhan shared.

When the question of social media influencers was brought up, Samhan argued: “The real competition is not with influencers. It’s with low-quality content. Credibility is what distinguishes news institutions from content creators.”

Journalism is built on trust, resources, and responsibility while influencers often lack verification and accountability, he said.

Reflecting on what the rise of digital platforms means for television, Al-Ibrahim said they are not alternatives, but complementary partners.

“Television creates shared moments; platforms create personalized experiences,” and the average consumer could greatly benefit from both.