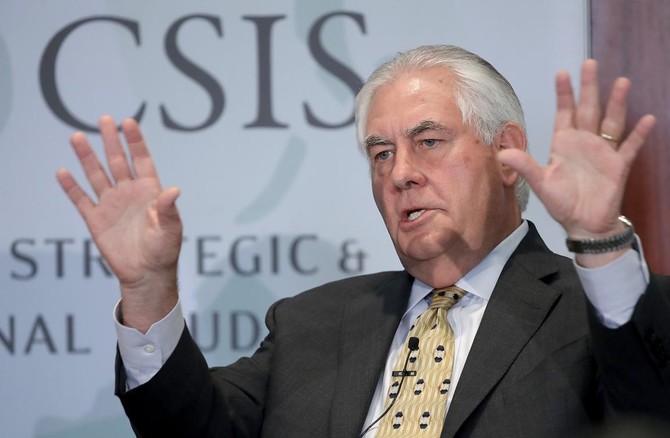

WASHINGTON: The United States will again try to resolve a Gulf crisis that Washington has alternatively fueled or tried to soothe, as Secretary of State Rex Tillerson heads back to the region.

The top US diplomat did not himself hold out much hope of an immediate breakthrough in the stand-off between Qatar and Saudi Arabia, but the trip may clarify the issues at stake.

“I do not have a lot of expectations for it being resolved anytime soon,” Tillerson admitted on Thursday, in an interview with the Bloomberg news agency.

“There seems to be a real unwillingness on the part of some of the parties to want to engage.”

Nevertheless, President Donald Trump’s chief envoy is to leave Washington this weekend for Saudi Arabia and from there head on to Qatar, to talk through a breakdown in ties.

Trump, having initially exacerbated the split by siding with Riyadh and denouncing Qatar for supporting terrorism at a “high level,” has predicted the conflict will be resolved.

Tillerson, a former chief executive of energy giant ExxonMobil, knows the region well, having dealt with its royal rulers while negotiating oil and gas deals.

But the latest diplomatic spat is a tricky one, pitching US allies against one another even as Washington is trying to coordinate opposition to Iran and to Islamist violence.

Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates and Egypt cut diplomatic relations with Qatar in June, accusing it of supporting terrorism and cozying up to Iran.

The sides have been at an impasse since then, despite efforts by Kuwait — and a previous unsuccessful trip by Tillerson in July — to mediate the crisis.

The blockade has had an impact on Qatar’s gas-rich economy, and created a new rift in an already unstable Middle East, with Turkey siding with Qatar and Egypt with the Gulf.

Iran, Washington’s foe, only stands to benefit from a split in the otherwise pro-Western camp, and US military leaders are quietly concerned about the long-term effects.

Trump, after initially vocally support the effort to isolate Qatar despite its role as a military ally and host of a major US air base, has not called for a negotiated resolution.

Tillerson says there has been little movement.

“It’s up to the leadership of the quartet when they want to engage with Qatar because Qatar has been very clear — they’re ready to engage,” he said.

“Our role is to try to ensure lines of communication are as open as we can help them be, that messages not be misunderstood,” he said.

“We’re ready to play any role we can to bring them together but at this point it really is now up to the leadership of those countries.”

Simon Henderson, a veteran of the region now at the Washington Institute of Near East Policy, said the parties may humor US mediate but won’t want to lose face to each other.

“Tillerson will say: ‘Come on kids, grow up and wind down your absurd demands. And let’s work on a compromise on your basic differences’,” he said.

Riyadh’s demands of Qatar are not entirely clear, but it has demanded Qatar cool its ties with Iran, end militant financing and rein in Doha-based Arabic media like Al-Jazeera.

“I haven’t seen Qatar make any concession at all other than to say negotiation is the way out of this,” Henderson said.

“The problem is that people, mainly the Saudis and the Emiratis, don’t want to loose face. It needs America to step in, but to save face, they should try to make this a Gulf-mediated enterprise with American support.”

Kuwait has tried to serve at a mediator, with US support, but the parties have yet to sit down face-to-face.

After his visit to Riyadh and Doha, Tillerson is to fly on to New Delhi in order to build what he said in a speech this week could be a 100-year “strategic partnership” with India.

Tillerson will stop in Islamabad to try to sooth Pakistani fears about this Indian outreach, but also pressure the government to crack down harder on Islamist militant groups.

Tillerson heads back to deal with Gulf crisis

Tillerson heads back to deal with Gulf crisis

Ramadan lanterns: A symbol of celebration

CAIRO: Muslims around the world are observing Ramadan, a month of dawn-to-dusk fasting, intense prayer and charity.

The holy month has long been associated with a rich tapestry of customs and traditions that define its unique celebrations.

Among the most prominent symbols of these festivities is the Ramadan lantern, a cherished emblem that illuminates streets and homes, reflecting the spiritual and cultural essence of the season.

In the historic districts of Cairo — such as Al-Hussein, Al-Azhar and Sayyida Zeinab — millions of Egyptians gather to celebrate Ramadan.

These neighborhoods are transformed into vibrant scenes of light and color, adorned with elaborate illuminations and countless Ramadan lanterns that hang across streets and balconies.

Vendors line the bustling alleys, offering a wide array of goods associated with the sacred month.

Foremost among these cherished items is the Ramadan lantern, which remains the most iconic and sought-after symbol of the season, embodying both tradition and festivity.

The lantern, in its earliest form, served as a vital source of illumination in ancient times.

Initially, torches crafted from wood and fueled with oils were used to light homes and pathways.

During the Middle Ages, Egyptians advanced their methods of lighting, developing oil lamps and decorative lanterns. In the Mamluk era, streets were illuminated on a wider scale, and artisans excelled in architectural innovation, producing intricately designed lanterns adorned with refined artistic motifs.

Gamal Shaqra, professor of modern history, told Arab News: “The story of the Ramadan lantern is widely traced back to the Fatimid era, with several narratives surrounding its origin. One account links it to Jawhar Al-Siqilli, the general who founded Cairo and built Al-Azhar Mosque, and to the arrival of Caliph Al-Muizz li-Din Allah in 969 A.D.

“According to this, Egyptians welcomed the Fatimid caliph by carrying lanterns to light his path, using them as both illumination and a gesture of celebration.”

He added: “Following this historic scene, lanterns began to be used to light streets and public spaces. Over time, the lantern evolved into a defining symbol of Ramadan festivities, as children took to the streets carrying their brightly lit lanterns and chanting traditional songs celebrating the holy month.

“The tradition continued to flourish during the Ayyubid and Mamluk periods, with lantern designs becoming increasingly diverse. In the era of Mohammad Ali, the craft saw further development, as lanterns were manufactured from metal sheets and fitted with colored glass, marking a significant evolution in both design and production.”

Methods of manufacturing the Ramadan lantern have diversified over time, alongside the evolution of its artistic designs in the modern era.

With the advancement of tools and technology, merchants have increasingly introduced wooden lanterns crafted using laser-cut techniques, offering intricate patterns and contemporary styles.

Despite these innovations, handcrafted lanterns continue to retain their distinctive value and authenticity. Made by skilled artisans, these traditional pieces remain deeply cherished, preserving the spirit of heritage and craftsmanship associated with the holy month.

Artist Mohamed Abla told Arab News that the design of the Ramadan lantern was inspired by the form of the mishkat — the ornate niche found in mosques that embodies Islamic art and traditionally serves as a source of illumination.

He added that the lantern had long been a subject for visual artists, who had depicted it in their paintings as a symbol of folk heritage and the enduring traditions associated with celebrating the holy month.

During a tour of popular marketplaces, a clear variation in lantern prices was noted, reflecting the craftsmanship and effort invested in their production.

In the tourist markets along Al-Moeaz Street, brass and bronze lanterns are prominently displayed in antique shops, showcasing elaborate designs that appeal to both visitors and collectors seeking traditional Ramadan decor.