ROME: The UN refugee agency is seeking to open a refugee transit center in Tripoli early next year to resettle or evacuate as many as 5,000 of the most vulnerable refugees out of Libya each year, a senior UN official said on Friday.

It is a small fraction of the total number of Libya’s migrant population, estimated at as many as 1 million, but would be a welcome outlet for the 43,000 refugees that the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates are now trapped in Libya.

“We hope to have the (written) authorization soon,” Roberto Mignone, the UNHCR’s representative in Libya, told Reuters in Rome. The UN-backed Tripoli government has already approved the project verbally, he said.

The center, where migrants will be able to come and go as they please, will be in a former immigration police training facility. Once refurbished, it will be able to temporarily accommodate as many as 1,000 refugees and could be running by early 2018, Mignone said.

Italy has become the main migrant route to Europe since an agreement between the EU and Turkey shut down smuggling through Greece last year, but arrivals have fallen sharply since July, when an armed group clamped down on departures.

With the backing of the European Union, Italy has financed, trained and equipped by the Tripoli-based coast guard. With a national election due early next year, Italy is also promising tens of millions of euros to Prime Minister Fayez Al-Seraj and municipal governments to put a stop to smuggling.

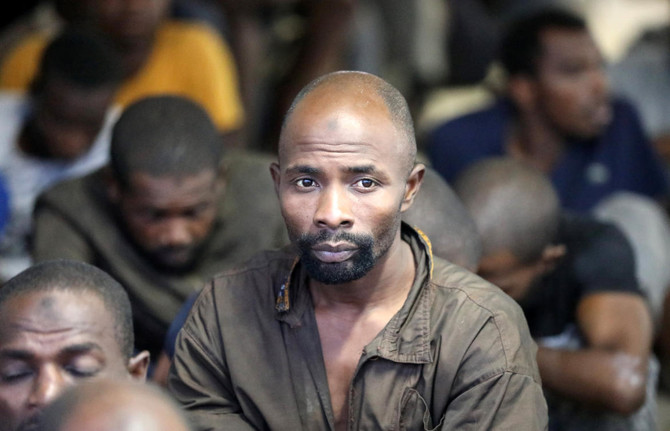

This strategy has drawn criticism from humanitarian groups that point to the dire conditions inside state detention centers, where Mignone said some 6,000 now are held, and in the much more numerous “camps” where smugglers hold migrants, often extorting them or forcing them to labor for free.

Italian Interior Minister Marco Minniti has said he is depending on the UN refugee and migration agencies to improve conditions for refugees and migrants now trapped in Libya.

“We can’t be the only solution,” Mignone said, also because Libya remains very dangerous and international staff still have very limited access to the country.

“There are still many risks” for international staff, he said. “A month-and-a-half ago, there was an attack on a UN convoy 30 km from Tripoli with bazookas and machine guns. It was a miracle that the worst was avoided.”

Some 1,200 of the most vulnerable refugees — which includes women, children, the sick or disabled and the elderly — have already been released from detention centers at the request of the UNHCR, and about 800 more should be let out soon, Mignone said.

While the UNHCR hopes to resettle many of them, it is a lengthy process. Many countries do not have a permanent diplomatic presence in Tripoli, further complicating matters.

So the agency will seek to evacuate most of them, Mignone said, to emergency transit centers in Romania, Slovakia or even Costa Rica, where they will have more time to apply for resettlement. The agency is currently working to open another emergency transit center in Niger, he said.

UN aims to open Libyan transit center early next year

UN aims to open Libyan transit center early next year

‘No one to back us’: Arab bus drivers in Israel grapple with racist attacks

- “People began running toward me and shouting at me, ‘Arab, Arab!’” recalled Khatib, a Palestinian from east Jerusalem

JERUSALEM: What began as an ordinary shift for Jerusalem bus driver Fakhri Khatib ended hours later in tragedy.

A chaotic spiral of events, symptomatic of a surge in racist violence targeting Arab bus drivers in Israel, led to the death of a teenager, Khatib’s arrest and calls for him to be charged with aggravated murder.

His case is an extreme one, but it sheds light on a trend bus drivers have been grappling with for years, with a union counting scores of assaults in Jerusalem alone and advocates lamenting what they describe as an anaemic police response.

One evening in early January, Khatib found his bus surrounded as he drove near the route of a protest by Israel’s ultra-Orthodox Jewish community.

“People began running toward me and shouting at me, ‘Arab, Arab!’” recalled Khatib, a Palestinian from east Jerusalem.

“They were cursing at me and spitting on me, I became very afraid,” he told AFP.

Khatib said he called the police, fearing for his life after seeing soaring numbers of attacks against bus drivers in recent months.

But when no police arrived after a few minutes, Khatib decided to drive off to escape the crowd, unaware that 14-year-old Yosef Eisenthal was holding onto his front bumper.

The Jewish teenager was killed in the incident and Khatib arrested.

Police initially sought charges of aggravated murder but later downgraded them to negligent homicide.

Khatib was released from house arrest in mid-January and is awaiting the final charge.

Breaking windows

Drivers say the violence has spiralled since the start of the Gaza war in October 2023 and continued despite the ceasefire, accusing the state of not doing enough to stamp it out or hold perpetrators to account.

The issue predominantly affects Palestinians from annexed east Jerusalem and the country’s Arab minority, Palestinians who remained in what is now Israel after its creation in 1948 and who make up about a fifth of the population.

Many bus drivers in cities such as Jerusalem and Haifa are Palestinian.

There are no official figures tracking racist attacks against bus drivers in Israel.

But according to the union Koach LaOvdim, or Power to the Workers, which represents around 5,000 of Israel’s roughly 20,000 bus drivers, last year saw a 30 percent increase in attacks.

In Jerusalem alone, Koach LaOvdim recorded 100 cases of physical assault in which a driver had to be evacuated for medical care.

Verbal incidents, the union said, were too numerous to count.

Drivers told AFP that football matches were often flashpoints for attacks — the most notorious being those of the Beitar Jerusalem club, some of whose fans have a reputation for anti-Arab violence.

The situation got so bad at the end of last year that the Israeli-Palestinian grassroots group Standing Together organized a “protective presence” on buses, a tactic normally used to deter settler violence against Palestinians in the Israeli-occupied West Bank.

One evening in early February, a handful of progressive activists boarded buses outside Jerusalem’s Teddy Stadium to document instances of violence and defuse the situation if necessary.

“We can see that it escalates sometimes toward breaking windows or hurting the bus drivers,” activist Elyashiv Newman told AFP.

Outside the stadium, an AFP journalist saw young football fans kicking, hitting and shouting at a bus.

One driver, speaking on condition of anonymity, blamed far-right National Security Minister Itamar Ben Gvir for whipping up the violence.

“We have no one to back us, only God.”

‘Crossing a red line’

“What hurts us is not only the racism, but the police handling of this matter,” said Mohamed Hresh, a 39-year-old Arab-Israeli bus driver who is also a leader within Koach LaOvdim.

He condemned a lack of arrests despite video evidence of assaults, and the fact that authorities dropped the vast majority of cases without charging anyone.

Israeli police did not respond to AFP requests for comment on the matter.

In early February, the transport ministry launched a pilot bus security unit in several cities including Jerusalem, where rapid-response motorcycle teams will work in coordination with police.

Transport Minister Miri Regev said the move came as violence on public transport was “crossing a red line” in the country.

Micha Vaknin, 50, a Jewish bus driver and also a leader within Koach LaOvdim, welcomed the move as a first step.

For him and his colleague Hresh, solidarity among Jewish and Arab drivers in the face of rising division was crucial for change.

“We will have to stay together,” Vaknin said, “not be torn apart.”