YANGON: A rights group has called for targeted sanctions and an arms embargo against the Myanmar military in response to an offensive that has sent 410,000 Rohingya Muslims fleeing to Bangladesh to escape what the United Nations has branded ethnic cleansing.

The latest spasm of violence in western Myanmar’s Rakhine State began on Aug. 25, when Rohingya insurgents attacked police posts and an army camp, killing about 12 people.

Rights monitors and fleeing Rohingya say Myanmar security forces and Rakhine Buddhist vigilantes responded with what they describe as a campaign of violence and arson aimed at driving out the Muslim population.

Buddhist-majority Myanmar rejects that, saying its forces are carrying out clearance operations against the insurgents of the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, which claimed responsibility for the August attacks and similar, smaller, raids in October.

The Human Rights Watch group said Myanmar security forces were disregarding condemnation by world leaders over the violence and the exodus of refugees, and the time had come to impose tougher measures that Myanmar’s generals could not ignore.

“The United Nations Security Council and concerned countries should impose targeted sanctions and an arms embargo on the Burmese military to end its ethnic cleansing campaign,” the groups said in a release.

About a million Rohingya lived in Rakhine State until the recent violence. Most face draconian travel restrictions and are denied citizenship in a country where many Buddhists regard them as illegal immigrants from Bangladesh.

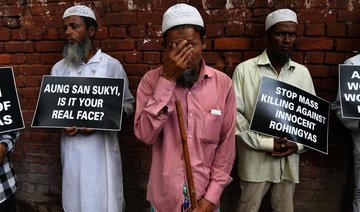

Myanmar government leader and Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi has faced a barrage of criticism from abroad for not stopping the violence.

The military remains in charge of security policy and there is little sympathy for the Rohingya in a country, also known as Burma, where the end of army rule has unleashed old animosities and the military campaign in Rakhine State has wide support.

Suu Kyi is due to make her first address to the nation on the crisis on Tuesday.

The United States has called for the protection of civilians and a deputy assistant secretary of state, Patrick Murphy, is due in Myanmar this week.

He will travel to Sittwe, the capital of Rakhine State, to meet government officials and representatives of different communities, including Rohingya, but he is not seeking to travel to the conflict zone in northern Rakhine State.

‘Strategically Sound’

Human Rights Watch called for governments to “impose travel bans and asset freezes on security officials implicated in serious abuses; expand existing arms embargoes to include all military sales, assistance, and cooperation; and place a ban on financial transactions with key ... military-owned enterprises.”

For years, the United States and other Western countries imposed sanctions on Myanmar aimed at ending military rule and supporting Suu Kyi’s campaign for democracy. Myanmar’s response was to build closer ties with giant northern neighbor, China.

US-Myanmar ties have been improving since the military began withdrawing from the running of the country in 2011, and paved the way for a 2015 election won by Suu Kyi’s party.

A Trump administration official said the violence made it harder to build warmer ties, and there would likely be some “easing” of the process in the short term, but he did not expect a return to sanctions.

“People are too invested in the last five years of thawing, which is understood by everyone to be strategically sound,” said the official, who declined to be identified.

“Long-term, the trajectory is probably tighter relations.”

Bangladesh is struggling to cope with the influx of refugees, many of them women and children, and aid workers fear people could die due to a lack of food, shelter and water, given the huge numbers fleeing the violence.

Bangladesh has said all refugees must go home. Myanmar has said it will take back those who can verify their citizenship.

Suu Kyi’s foreign supporters and Western governments that have backed her will be hoping to see her make a commitment to protect the rights of the Muslim minority in her Tuesday address.

Suu Kyi’s domestic supporters could be disappointed if she is perceived to be caving in to foreign pressure and taking the side of a Muslim minority blamed for initiating the violence.

In a rare expression of support for the Rohingya from within Myanmar, a group from the Karen ethnic minority, called for the military to halt its operations.

“We have seen the devastation caused by this criminal military,” the Karen Women’s Organization said, referring to decades of army operations against autonomy-seeking Karen insurgents that sent more than 100,000 villagers fleeing to Thailand.

“They must be treated like the war criminals they are ... Economic sanctions should be also considered,” the group said.

Karen insurgents have made peace with the government.