CAIRO: Ballet dancer Fady el-Nabarawy feels he can finally breathe again the moment he enters the gates of the Cairo Opera House after a commute from his ramshackle, poor neighborhood. This is where he and his fellow dancers practice, perform, love and create.

“Every day, I cannot wait to come here. My oxygen is here,” he said.

Ballet is in its own bubble in Egypt, removed from the surrounding society. The elite Western art form is far from Egypt’s own rich traditions of classical Arabic music and dance, let alone the electro-beat sweeping the Arabic pop music scene. The country has grown more conservative, and in the eyes of some Muslims, ballet is outright “nudity.” Social pressure to conform is overpowering, so the idea of someone dancing on stage in tights strikes many Egyptians as just plain odd.

Still, the young men who found their passion dancing ballet are hardly isolated elites. They’re firmly rooted in the middle and lower-middle classes, managing to carve out their own Bohemian zone of diversity and creativity.

Ballet’s audience in Egypt may be limited, but it’s enthusiastic. On a recent night at the Opera House, located on an upscale residential island in the Nile River, the Cairo Ballet Company brought a packed house to its feet with a rousing performance of “Zorba,” a ballet based on the same novel as the movie “Zorba the Greek.”

The audience — men mainly in suits, women in evening gowns, many wearing Muslim headscarves — cheered a dazzling finale by the two leads. Ahmed Nabil, tall and slender, leaped in classical routines while Hani Hassan, playing Zorba, mixed in the machismo of traditional Greek dance, slapping his thighs and kicking up his heels. Hassan blew kisses to the crowd and led them in clapping to the music.

The ovations pulled them out for three encores. Afterward, people swarmed to congratulate Nabil and his wife and fellow dancer, Italian ballerina Alice De Nardi.

“And to think my parents wanted me to drop out of ballet school,” Nabil said.

In the 60-member, state-funded company, almost all the ballerinas are foreigners, coming from Serbia, Italy, Greece, Japan, Ukraine and Greece, with only a handful of Egyptians. The male dancers, in contrast, are almost all Egyptian.

From childhood, the male dancers learned to keep ballet a secret. It was the best way to avoid mockery, bigotry, innuendos about their sexual orientation or just ignorant curiosity — constant questions like “Can you walk on your toes?” or “Do you wear tights?” Hassan told people he did gymnastics when they asked why he was getting so muscular.

“When I read music on the metro and some guy asks me what I’m doing, I tell him I’m with the conservatory,” said el-Nabarawy.

El-Nabarawy came to ballet because of a moment of despair as a 7-year-old. He was a reclusive child, and his teachers often yelled at him and hit him. So one day he skipped school and hid all morning behind a parked car near his home.

When his mother found out, she promised to move him to another school the next year. His father saw an ad for the arts academy. Its main attraction was that it was near their home. El-Nabarawy applied to the conservatory and failed, but then was accepted in ballet.

His mother wondered if that was more suitable for girls, but in the end didn’t object.

“I became a ballet dancer by chance but, glory to God, I’m told I was born to be a ballet dancer,” he said.

El-Nabarawy, now 29, said he’s proud both of being a ballet dancer and of being from Cairo’s district of Omraniyah, though it is not always easy.

Once farmland on Cairo’s western edges, Omraniyah is now a crowded district of shoddy, cramped concrete-and-brick apartment towers, mostly built up illegally as migrants poured in from southern Egypt looking for jobs and a better life. Narrow streets are jammed with cars, trucks, donkey carts and motorcycle rickshaws, or tuk-tuks, often driven by children.

El-Nabarawy lives with his parents and brother on the top floor of a six-story walk-up. It looks out over a cityscape of satellite dishes, dangling wires, exposed rebar and jagged concrete.

But he’s hardly there. “My life now is totally divorced from Omraniyah,” he said. “I just go home to sleep.”

Instead, his time is spent in the refuge of the Opera House complex.

In rehearsals, as the dancers sweat and strain, it becomes clear how it’s a space for some diversity. Some of the men sport a “zebiba,” a bruise on the forehead from prostrating during Muslim prayers, and head out to pray during rehearsal breaks. Others have pony tails, a style that still gets disapproving looks on the streets in Egypt.

The male and female dancers mingle, chat and smoke together. Like his Zorba, the 39-year-old Hassan, the son of an army officer, exudes joie-de-vivre, flirting with ballerinas and showing off his fluency in Russian — his ex-wife was a Russian dancer. He proclaims repeatedly he’s traveling soon to Spain for a guest performance, a badge of honor.

At least six of the male dancers are married to or dating foreign female dancers.

It’s often a lesson in broadening horizons. El-Nabarawy describes himself as a practicing Muslim — he sometimes posts religious material on Facebook — and his girlfriend, Kristina Lazovic, is a Christian Serb. El-Nabarawy grew up hearing about Serbian massacres of Bosnian Muslims during the Balkan wars in the 1990s. Now he’s getting the Serbs’ side in lively discussions with Lazovic.

“I’m now convinced atrocities were committed by both sides,” he said.

Fellow dancer Waleed Eskaros and his fiancée, Greek ballerina Antigoni Tsiouli, are making their own cultural adjustments. Both are Christian, but he’s Coptic Orthodox and she’s Greek Orthodox.

He wants his Church’s blessing, but it won’t marry them unless she converts, something she and her family refuse. So “it looks like I will marry in a Greek Orthodox church. They are more flexible.”

Presiding over the rehearsals is Madame Erminia Gambarelli, the artistic director. She’s the Italian widow of Abdel-Moneim Kamel, the giant of Egyptian ballet who rebuilt the company in the 1990s, mentored many of its current dancers and died in 2013.

Ballet in Egypt has been immersed in politics from the start.

The national company was founded by the government in 1958 as a way to strengthen the bond with Egypt’s top ally at the time, the Soviet Union. In the 1990s, President Hosni Mubarak’s government revived ballet as part of a more capitalist-driven prestige project, building the Opera House complex with Japanese backing.

Ballet was thrust onto the political stage after the Muslim Brotherhood came to power following the 2011 uprising that ousted Mubarak.

Islamist lawmakers demanded an end to state funding for the company. One legislator denounced ballet as the “art of nakedness.”

Some dancers had often worried privately over whether ballet was acceptable under their faith, Eskaros said. The Islamists tipped them over the edge, and several quit, declaring it “haram,” or forbidden.

Fears over the fate of ballet and other arts became a rallying point in the popular campaign against the Brotherhood. When an Islamist was named culture minister in 2013, artists and intellectuals held a month-long protest outside the minister’s office.

It turned into a nightly street party of singing, poetry and dancing. Hassan, Eskaros and others in the company performed a dozen times. “I thought I’d dance on the street to let people decide for themselves whether ballet is haram or not,” Hassan said.

The military ousted the Brotherhood in July 2013.

Hassan remains a fierce opponent of “conservative ideologies” he says pervade the country. “People inject religion into everything ... always talking about what this sheikh said and what that sheikh said.”

The company is still recovering from the turmoil. Most foreign dancers fled amid the 2011 uprising. Foreign ballerinas are back, but now the company — like the rest of Egypt — struggles with austerity measures imposed by the government to repair the damaged economy.

Funds are tighter. After devaluations, even the best paid dancers make the equivalent of only a few hundred dollars a month. Nabil and Hassan run ballet schools, making a living and spreading the art. Others teach ballet or take up day jobs, mostly in the government.

“I’m not happy with the quality of our work,” said the 34-year-old Nabil. “The company is now rebuilding.”

Still, he said, his entire life is within the Opera House walls, where he’s been coming since he was 11.

“This is where I am famous. Once I go through the gate and onto the street, I cease to exist as who I am.”

Ballet isolated in Egypt but it fires passions

Ballet isolated in Egypt but it fires passions

Moroccan photographer Hassan Hajjaj captures the culture of AlUla

- The acclaimed Moroccan photographer discusses his recent show in Saudi Arabia

DUBAI: Early in February this year, Moroccan contemporary artist and photographer Hassan Hajjaj was given a reminder of just how high his star has risen. Within a few days of each other, Hajjaj had shows opening in the US, Morocco, and — as part of AlUla Arts Festival — Saudi Arabia.

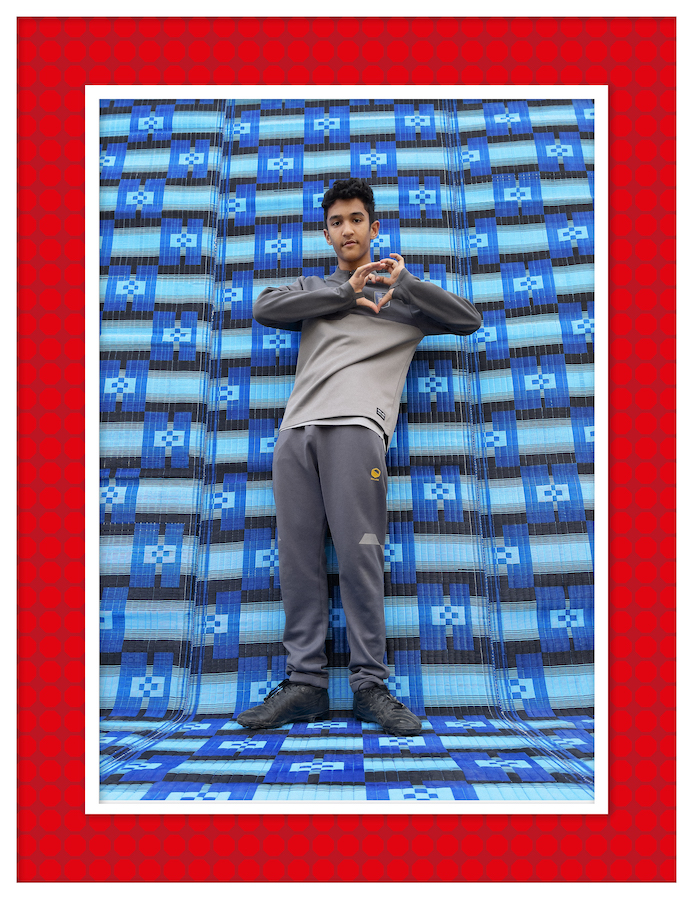

Hajjaj’s playful portraiture, which incorporates vivid color, funky clothing (almost all of which he designs himself), geometric patterns, and — often — vintage brands from the MENA region, has made him internationally popular, and his instantly recognizable style has established him as one of the world’s leading photographers.

His show in AlUla consisted of images that he shot in the ancient oasis town in February 2023. That visit was initially supposed to involve shoots with around 20 local people. It’s the kind of thing he’s done a few times before, including in Oman and Abu Dhabi. “It’s always a good opportunity to get to know the culture and the people,” Hajjaj tells Arab News.

But, as he says himself, he arrived in AlUla as “an outsider,” so needed a team on the ground to persuade locals to come and sit (or stand, in most cases) for him.

“It was a bit tough, in the beginning, for them to find people,” Hajjaj explains. “But because it was during a period when lots of art things were happening in AlUla, there were lots of people coming from outside AlUla as well. So we opened it up. I basically said, ‘Just come.’

“In the end lots of people turned up, not just locals — people from Riyadh, Jeddah, and people (from overseas) too. I think I shot around 100 people over a few days. So it was a great opportunity,” he continues. “To get to shoot that many people over three days — organizing something like that for myself might take a year. So, as long as I have the energy, when I get these opportunities — you know, I’m in AlUla with this eclectic bunch of people — I’d rather go and grind it, really work hard, and have that moment.”

A Hassan Hajjaj shoot isn’t your regular portrait shoot, of course. “It’s almost like a performance,” he says. “There’s music, people dress up, it’s like a day out for them, taking them out of themselves for a few hours.”

He followed the same modus operandi in AlUla. “We got an ambience going. It was fun, there was music… I shot in this beautiful old school that was one of the first girls’ schools in Saudi Arabia, from the Sixties. Upstairs was like a museum — everything was like a standstill from the Seventies and Eighties; even the blackboards had the chalk and the writing from that time,” he says.

A crucial part of Hajjaj’s practice is to ensure that his subjects are at ease and feel some connection with him (“comfortable” is a word he uses several times when talking about his shoots). While all his portraits bear his clearly defined style, it’s important to him that they should also show something unique to the people in them.

“It’s that old thing about capturing the spirit of the person in that split second, you know? I’m trying to get their personality and body language in the image,” he says. “Quite often I’m shooting in the street, outdoors, so (the subjects) can start looking at other people, thinking, ‘Are they looking at me?’ So I usually say, ‘Listen. This is a stage I’m building for you. I’m dressing you up, and we’re going to have fun.’ Then I just try and find that personality that can come out and make the image stronger. With some people, though, saying almost nothing can be better — just getting on with it. I try to kind of go invisible so it’s the camera, not the person, that’s doing the work. The best pictures come out when there’s some kind of comfortable moment between me and the person and the camera.”

It’s the way he’s worked since the beginning — a process that developed organically, as most of his early portraits were of “friends or friends of friends.”

“There’s a comfort in that because you have a relationship with them. It made it easy,” he says. “And that taught me about how important it is to build trust with people to get into that comfortable zone. But as time went on, obviously, people could see the stuff in the press or on social media, so then people started, like, asking to be shot in that manner; maybe they’ve studied the poses of certain people and stuff like that, so they come ready to do some pose they’ve seen in my pictures. That’s quite funny.”

The work that was on display over the past two months in Hajjaj’s “AlUla 1445” is a perfect example of what he tries to achieve with his shoots. The images are vibrant, playful, and soulful, and the subjects run from a local goatherder through the AlUla football team to bona fide superstars: the US singer-songwriter Alicia Keys and her husband Swizz Beatz.

Hajjaj says he has a number of favorites “for different reasons,” including the goatherder.

“He brought in two goats and it became quite abstract when you put all of them together. I was playing with that notion of the person; you could see that’s his life and even the goats look happy,” he explains. “I wanted to make sure they had that shine in the image as well. I got some great shots of him.”

The Alicia Keys and Swizz Beatz shoot has been a long time in the making. Hajjaj first met Swizz Beatz a decade ago, and they have been in touch intermittently ever since. The idea of a shoot with Keys first came up about five years ago, but logistics had always got in the way. But since they were playing a concert in AlUla at the same time as Hajjaj was there, it finally happened, on Hajjaj’s last day, with perhaps an hour left before the light faded.

I ask Hajjaj if his approach to shooting celebrities differs from his shots of “ordinary” people.

“There’s probably not that much difference,” he says. “They’re coming into my world, so, again, it’s just making sure they’re comfortable with you and you’re comfortable with them; not looking at them (as celebrities). The only thing is you have to imagine they’ve been shot thousands of times — by top photographers, too — so they’re going to have their ways. So I just have to lock in with them and find that comfortable space between the sitter and me.”

And then there’s Ghadi Al-Sharif.

“It’s a beautiful picture. She’s got this smile, with her hand over her face. For me, that one really presents the light and the energy of AlUla,” Hajjaj says. “It captures the new generation.”

Ithra showcases Arab creatives at Milan Design Week

- The Dhahran-based cultural center took part in the prestigious Italian fair last month

DUBAI: The King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture (Ithra) participated in Milan Design Week between Apr. 16 and 21. It was the second time Ithra has taken part in the annual event — a significant entry in Italy’s cultural calendar.

Ithra was founded with the goal of developing Saudi creative talent. Noura Alzamil, the center’s head of programs, has seen its influence mushroom since the beginning and continues to be in awe of her country’s rapidly developing art scene.

“Practicing it and seeing it every day around you and reading about it in articles and seeing that interaction and conversation on a national level, is really heartwarming,” she says.

“We’ve been active for the past 13 years, in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture, doing a lot of enriching programs, activations, bringing in new content and experimenting with our community and exposing them to arts, museums theatre, films,” Alzamil adds. “To me, investing in Saudi minds helps them excel in the future. I believe heavily in taking care of young talents, supporting professionals and having a global conversation.”

Ithra also houses what it bills as the region’s first ‘Material Library,’ displaying a variety of raw design materials. “Artists are all about experimentation,” Alzamil says. “The Material Library hosts hundreds of different materials that designers can come and play with.”

A cornerstone of Ithra’s programming is Tanween, a four-day conference that showcases creative designs from university students and emerging creatives from the region. The products from the conference are then exhibited in public events, such as Milan Design Week.

“To me, and to Ithra, it’s really important to showcase our efforts and Saudi and Arab designers in such festivals. Being presented among our peers there is something that we really care about,” says Alzamil. This year, Ithra presented an exhibition of items created by MENA artists in a wide range of mediums in Milan — the first time the center has presented a full show there.

Entitled “From Routes to Roots” and presented in collaboration with Isola (a Milan-based digital platform), the show included glasswork, clay, rugs and lighting. One of the key ideas of the exhibition was to demonstrate how creatives are preserving heritage and the Earth through circular design, which helps to eliminate waste from production.

“They used a lot of integrating bio materials, natural resources, household and industrial waste to come up with these innovative designs and objects that showcase and support sustainability,” Alzamil says.

Participating creatives hailing from the Levant, North Africa and the Gulf included Marwa Samy Studio, Ornamental by Lameice, Joe Bou Abboud, T Sakhi Studio, Bachir Mohamad, Studio Bazazo, and Mina Abouzahra.

“The exhibition draws inspiration and expertise from ancestral culture pairing it with cutting-edge craftsmanship, in a demonstration of how emerging talents can breathe fresh life into the design landscape, bridging the gap between tradition and innovation,” according to a press release.

Lebanese designer Bou Abboud presented a triad of round lighting fixtures that he says pay tribute to old Qatari jewelry, particularly long necklaces.

One of the more delicate pieces on view came courtesy of Jerusalem-based Palestinian designer Lameice Abu Aker. Her light-toned vases, jugs and drinking glasses are fluid and bubbly. She showcased a molecular-looking, violet vase called “Chemistry!” On Instagram, Abu Aker’s brand posted that the piece is “the perfect fusion of art and science, crafted with precision and care by our skilled artisans. Mouth-blown, every curve and line reflects the magic of the chemical reactions that inspired its name.”

Hanging textiles were also noticeably dominant in Ithra’s display. For instance, Doha-based artists Bachir Mohamad and Ahmad Al-Emadi collaborated on geometrical, symbol-heavy, blue-and-white rugs that are an homage to traditional Gulf Sadu weaving, historically practiced by Bedouins.

“It was really exciting,” Alzamil says of the show. “The team received a lot of visitors and different players in the field. . . It’s bridging the gaps between Saudi and international communities.”

London’s Arab Film Club launches podcast focusing on Palestine

DUBAI: The Arab Film Club, a monthly gathering in London celebrating Arab cinema, launched a podcast on May 1.

Spearheaded by the club’s founder, Sarah Agha, an Irish Palestinian actress and writer, the inaugural five-episode season of the interview-based podcast will focus on Palestinian filmmakers and cinema’s role in cultural resistance.

The debut episode features Darin J. Sallam, director of “Farha,” Jordan’s Oscars entry in 2022. In other episodes, Agha interviews Lina Soualem, (“Bye Bye Tiberias”), Ameen Nayfeh (“200 Metres”) Annemarie Jacir (“Wajib”) and Farah Nabulsi (“The Teacher”).

Agha told Arab News, “It is so urgent right now to do anything and everything we can to keep talking about Palestine. So I thought, ‘Why not do some interviews with some of my favorite Palestinian directors and put them online so everyone can listen to them?”

Reflecting on Sallam’s episode, Agha highlighted the transformative potential of cinema. “She is linking educational talks with her film, and I do believe her film is like a tool of change,” the presenter said.

Agha said she found Soualem’s documentary particularly intriguing, due to its departure from the scripted films typically showcased at the Arab Film Club.

“I wanted to make an exception for Soualem’s film because it’s another portrayal of the Nakba, but in very different terrains — like, totally different,” she explained. “My father is from Tiberias, so I was also attracted to it for that reason.”

Agha believes her podcast is launching at a time when Palestinians are being censored in the arts.

“There’s been a lot of cancellations of events to do with Palestine and Palestinian narratives,” she said. “So I think the best thing that we can do is not succumb to hopelessness. The fact that they’re trying to silence voices means those voices are significant. You don’t silence something that’s irrelevant. For example, the fact that the Israeli government tried to pressure Netflix into removing Darin’s film shows that it’s important.”

Agha hopes the podcast will appeal to a diverse audience, including non-Arabs.

“That, for me, is a really big thing. If we just talk to ourselves all the time, we won’t really get any further with reaching a wider audience,” she said.

The Weeknd donates $2 million for humanitarian aid in Gaza

DUBAI: Canadian singer The Weeknd has pledged to donate another $2 million to help feed families in Gaza, the United Nations’s World Food Programme reported.

The donation comes from the star’s XO Humanitarian Fund, which helps combat global hunger.

“This support will provide over 1,500 metric tons of fortified wheat flour, which can make over 18 million loaves of bread that can help feed more than 157,000 Palestinians for one month,” said WFP.

In December, the multi-platinum global recording artist, whose given name is Abel Tesfaye, donated $2.5 million to WFP from the fund, which he established in partnership with World Food Program USA. That equated to 4 million emergency meals, funding 820 tons of food parcels that could feed more than 173,000 Palestinians for two weeks.

Tesfaye, who was appointed a Goodwill Ambassador in October 2021, is an active supporter of WFP’s global hunger-relief mission. He, his partners and his fans have raised $6.5 million to date for the XO fund.

In total he has directed $4.5 million toward operations in Gaza and has sent $2 million to support WFP’s emergency food assistance for women and children in Ethiopia.

DJ Peggy Gou makes waves in the Middle East, eyes collaborations with Arab artists

ABU DHABI: South Korean DJ and singer Peggy Gou is no stranger to the Middle East. She wowed fans this week at the Louvre Abu Dhabi in the UAE, performing in celebration of the newly opened exhibition “From Kalila wa Dimna to La Fontaine: Travelling through Fables,” and revealed that she would consider collaborating with Arab artists.

She told Arab News the morning after the event: “I woke up this morning and was thinking what happened last night. It is one of those events that is so meaningful. I’ve been to Abu Dhabi twice just to see the exhibitions. It’s more than a museum to me. It is a community, where people even go to hang out. That’s how beautiful that place is.”

Gou was among the first performers to take the stage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi in front of an audience, she said.

“I know David Guetta did it once before without an audience during COVID-19 … It was my first time playing in Abu Dhabi. It was insane. It was a very, very special night, and I want to do more,” she added.

Gou incorporates Arab-inspired music into her performances, noting that “people just love it, and they love percussion.”

To the artist, music is like a feeling. “It is really hard to rationalize it,” she said. “When you love it, you just love it,” she added, expressing her admiration for Arab melodies.

“This is maybe the reason why people support my music, even though they don’t understand the language. Sometimes they just feel it, they just love it,” she explained.

“I love our music, but at the same time, I’m considering collaborating with an Arab artist because there are a lot of talented Arab musicians here,” she said. “I have many friends here who recommended me some artists, and I want to check it out.

“I never say no. I love making music with different languages.”

Gou has performed in Saudi Arabia multiple times.

“Every time I go there, it’s different. But what I can say is it’s always changing in a good way. In the very beginning, I felt like they weren’t going to understand my music,” she recalled.

But the DJ said that her last performance in AlUla was one of her favorites. “People were just shouting, screaming, and dancing as if there was no tomorrow,” she said.