ISLAMABAD: Pakistan’s anti-corruption watchdog has sealed numerous properties of a private real estate developer, M/s Bahria Town, for “defrauding people of billions of rupees,” Pakistani state media reported on Monday.

M/s Bahria Town, which claims to be Asia’s largest private real estate developer, has projects in several cities, including Islamabad, Lahore and Karachi, in the South Asian country.

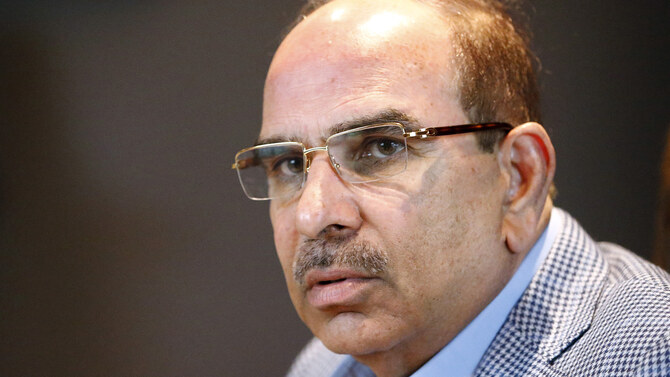

Pakistan’s National Accountability Bureau (NAB) said it had registered several cases of fraud and deception against Bahria Town owner Malik Riaz Hussain and others in Islamabad and Karachi courts, the Radio Pakistan broadcaster reported.

Hussain and his associates are accused of illegally occupying both government and private lands in Karachi, Rawalpindi and New Murree to establish housing societies without permission and defrauding people of billions of rupees.

“In recent actions related to this, numerous commercial and residential properties of Bahria Town in Karachi, Lahore, Takht Pari, New Murree/Golf City, and Islamabad have been sealed, including multi-story commercial buildings,” the Radio Pakistan report read.

“Additionally, hundreds of bank accounts and vehicles of Bahria Town have been frozen, and further actions in this regard are being carried out rapidly.”

There was no immediate comment from Bahria Town in response to NAB’s allegations.

The development comes more than a month after NAB filed a reference in an accountability court in Karachi, nominating Hussain, his son Ahmed Ali Riaz, former Sindh chief minister Syed Qaim Ali Shah and Sharjeel Inaam Memon, then local body minister and now information minister of Sindh, among 33 people for illegally transferring government land to M/s Bahria Town for its Bahria Town Karachi project in 2013 and 2014.

Hussain, who currently lives in Dubai, is one of Pakistan’s wealthiest and most influential businessmen and the country’s largest private employers. The anti-graft body this year said it had initiated the process to seek Hussain’s extradition from the United Arab Emirates (UAE), who was also charged in another land corruption case involving former prime minister Imran Khan and his wife.

A Pakistani court in January sentenced Khan to 14 years in prison and his wife, Bushra, to seven years, in the case in which they are accused of receiving land as a bribe from Hussain through the Al-Qadir charitable trust in exchange for illegal favors during Khan’s premiership from 2018 to 2022. Khan says he and his wife were trustees and did not benefit from the land transaction. Hussain too denies any wrongdoing relating to the case.

Hussain has recently launched a new project of luxury apartments in Dubai and NAB has prima facie evidence that certain individuals from Pakistan are illegally aiding him in this process by transferring their money to the UAE for investment in the project. These funds have been sent to foreign countries through “illegal means,” Radio Pakistan reported, citing the anti-graft body.

“Any funds transferred from Pakistan for this project will be considered money laundering, and legal action will be taken against the involved elements without discrimination,” the anti-corruption watchdog was quoted as saying.

“NAB will continue its legal actions against Bahria Town Pakistan without any delay or pressure to fully protect the rights of the citizens of Pakistan.”

Pakistan anti-graft body seals several properties of real estate developer for ‘defrauding’ citizens

https://arab.news/bhkz9

Pakistan anti-graft body seals several properties of real estate developer for ‘defrauding’ citizens

- M/s Bahria Town, which claims to be Asia’s largest private real estate developer, has several projects in Islamabad, Lahore, Karachi and other Pakistani cities

- Pakistan’s National Accountability Bureau last month booked Bahria Town owner Malik Riaz Hussain in a graft case, initiated process to extradite him from Dubai

‘Look ahead or look up?’: Pakistan’s police face new challenge as militants take to drone warfare

- Officials say militants are using weapons and equipment left behind after allied forces withdrew from Afghanistan

- Police in northwest Pakistan say electronic jammers have helped repel more than 300 drone attacks since mid-2025

BANNU, Pakistan: On a quiet morning last July, Constable Hazrat Ali had just finished his prayers at the Miryan police station in Pakistan’s volatile northwest when the shouting began.

His colleagues in Bannu district spotted a small speck in the sky. Before Ali could take cover, an explosion tore through the compound behind him. It was not a mortar or a suicide vest, but an improvised explosive dropped from a drone.

“Now should we look ahead or look up [to sky]?” said Ali, who was wounded again in a second drone strike during an operation against militants last month. He still carries shrapnel scars on his back, hand and foot, physical reminders of how the battlefield has shifted upward.

For police in the northwestern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province, the fight against militancy has become a three-dimensional conflict. Pakistani officials say armed groups, including the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), are increasingly deploying commercial drones modified to drop explosives, alongside other weapons they say were acquired after the US military withdrawal from neighboring Afghanistan.

Security analysts say the trend mirrors a wider global pattern, where low-cost, commercially available drones are being repurposed by non-state actors from the Middle East to Eastern Europe, challenging traditional policing and counterinsurgency tactics.

The escalation comes as militant violence has surged across Pakistan. Islamabad-based Pakistan Institute for Conflict and Security Studies (PICSS) reported a 73 percent rise in combat-related deaths in 2025, with fatalities climbing to 3,387 from 1,950 a year earlier. Militants have increasingly shifted operations from northern tribal belts to southern KP districts such as Bannu, Lakki Marwat and Dera Ismail Khan.

“Bannu is an important town of southern KP, and we are feeling the heat,” said Sajjad Khan, the region’s police chief. “There has been an enormous increase in the number of incidents of terrorism… It is a mix of local militants and Afghan militants.”

In 2025 alone, Bannu police recorded 134 attacks on stations, checkpoints and personnel. At least 27 police officers were killed, while authorities say 53 militants died in the clashes. Many assaults involved coordinated, multi-pronged attacks using heavy weapons.

Drones have also added a new layer of danger. What began as reconnaissance tools have been weaponized with improvised devices that rely on gravity rather than guidance systems.

“Earlier, they used to drop [explosives] in bottles. After that, they started cutting pipes for this purpose,” said Jamshed Khan, head of the regional bomb disposal unit. “Now we have encountered a new type: a pistol hand grenade.”

When dropped from above, he explained, a metal pin ignites the charge on impact.

Deputy Superintendent of Police Raza Khan, who narrowly survived a drone strike during construction at a checkpoint, described devices packed with nails, bullets and metal fragments.

“They attach a shuttlecock-like piece on top. When they drop it from a height, its direction remains straight toward the ground,” he said.

TARGETING CIVILIANS

Officials say militants’ rapid adoption of drone technology has been fueled by access to equipment on informal markets, while police procurement remains slower.

“It is easy for militants to get such things,” Sajjad Khan said. “And for us, I mean, we have to go through certain process and procedures as per rules.”

That imbalance began to shift in mid-2025, when authorities deployed electronic anti-drone systems in the region. Before that, officers relied on snipers or improvised nets strung over police compounds.

“Initially, when we did not have that anti-drone system, their strikes were effective,” the police chief said, adding that more than 300 attempted drone attacks have since been repelled or electronically disrupted. “That was a decisive moment.”

Police say militants have also targeted civilians, killing nine people in drone attacks this year, often in communities accused of cooperating with authorities. Several police stations suffered structural damage.

Bannu’s location as a gateway between Pakistan and Afghanistan has made it a security flashpoint since colonial times. But officials say the aerial dimension of the conflict has placed unprecedented strain on local forces.

For constables like Hazrat Ali, new technology offers some protection, but resolve remains central.

“Nowadays, they have ammunition and all kinds of the most modern weapons. They also have large drones,” he said. “When we fight them, we fight with our courage and determination.”