LONDON: Early voting has already begun in the US to decide who will form the next administration in what many believe is among the most consequential — and hotly contested — elections in a generation.

Almost every poll published over the past week has placed the two main contenders, Republican Donald Trump and Democrat Kamala Harris, neck and neck in the race for the White House.

Analysts predict the result could come down to just a handful of votes. The outcome could have huge implications not only for domestic policy, but also for the international order.

With extensive media coverage, election jargon, and an overwhelming volume of information, understanding the process can feel daunting. Here is a breakdown of all you need to know to survive election day.

The polls

Polls are often excellent indicators of general voter sentiment. However, recent US elections have shown they are far from foolproof.

In 2016, almost every major polling firm predicted Hillary Clinton would defeat Donald Trump. However, pollsters failed to capture Trump’s unexpected support, leading to a surprise victory that confounded many.

In 2020, polls correctly tipped Joe Biden as the likely winner, but underestimated the actual vote share Trump would receive. In the week before the election, polls gave Biden a seven-point lead, yet Trump managed to close the gap by several points on Election Day.

With most polls indicating a close race on Tuesday, many are wondering whether the pollsters have got it right this time around.

Electoral college

About 244 million Americans are eligible to vote in this year’s election. If the turnout matches 2020’s record 67 percent, about 162 million ballots will be cast across 50 states.

People cast their ballots during early in-person voting on Oct. 30, 2024, in Nashville, Tennessee. (AP)

A recent Arab News-YouGov poll indicated that Arab Americans are likely to vote in record numbers, with more than 80 percent of eligible voters saying they intend to participate — potentially swinging the outcome in several key states.

When voters cast their ballots, they do not vote directly for their preferred presidential candidate. Rather, they vote for a slate of “electors” who formally choose the president — a process known as the electoral college system.

Due to the quirks of this system, the candidate with the most votes nationally may not necessarily win the presidency. This was the case with Hillary Clinton in 2016 and Al Gore in 2000, both of whom won the popular vote but lost the election.

Former US Vice President Al Gore (left) won the popular vote in 2000 and so did former US first lady and senator Hilary Clinton in the 2016 election. But both lost the race because their rivals won more electoral votes. (AFP/File photos)l

The electoral college creates what could be defined as 51 mini elections — one in each state and another for Washington, D.C. In 48 states and D.C., the candidate with the majority vote takes all the electors from that state.

However, Maine and Nebraska have a different system, allocating electors by district, meaning their electoral votes may be split between candidates.

In total, 538 electors are distributed among the states. A candidate must secure at least 270 of these to win the presidency.

In the unlikely case that no candidate has the required 270 electoral college votes, then a contingent election takes place. This means the House of Representatives, the lower chamber of the US Congress, votes for the president.

How votes are counted

When the polls close on election day, the count begins. In most cases, in-person votes are counted first, followed by early and mail-in ballots.

Results from smaller or less contested states often come in early, while larger, key battleground states like Pennsylvania or Georgia may take hours — or days — to finalize due to stringent verification steps, including signature checks and ballot preparation for electronic scanning.

Jessica Garofolo (L), administrative services director for Allegheny County, demonstrates how the high-speed ballot scanner for mail-in ballots works during a media tour of the Allegheny County election warehouse in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on Oct. 30, 2024. (AFP)

States like Florida, where mail-in ballots are processed in advance, may report results relatively quickly. Other states, particularly those with late processing times for absentee ballots, might not finalize their tallies until days later.

State and local poll officials collect, verify, and certify the popular vote in each jurisdiction, following procedures for accuracy before final certification by governors and designated officials.

In response to unprecedented threats in 2020, many polling stations have now installed panic buttons, bulletproof glass and armed security to ensure safety across the more than 90,000 polling sites nationwide.

This combination image shows smoke pouring out of a ballot box on Oct. 28, 2024, in Vancouver, Washington (left) and a damaged ballot drop box displayed at the Multnomah County Elections Division office on Oct. 28, 2024, in Portland, Oregon. (KGW8 via AP/AP)

Mail-in and early votes

Although election day is held on the first Tuesday after Nov. 1, many Americans vote early. Early voting allows citizens to cast ballots in person, while others opt for mail-in ballots.

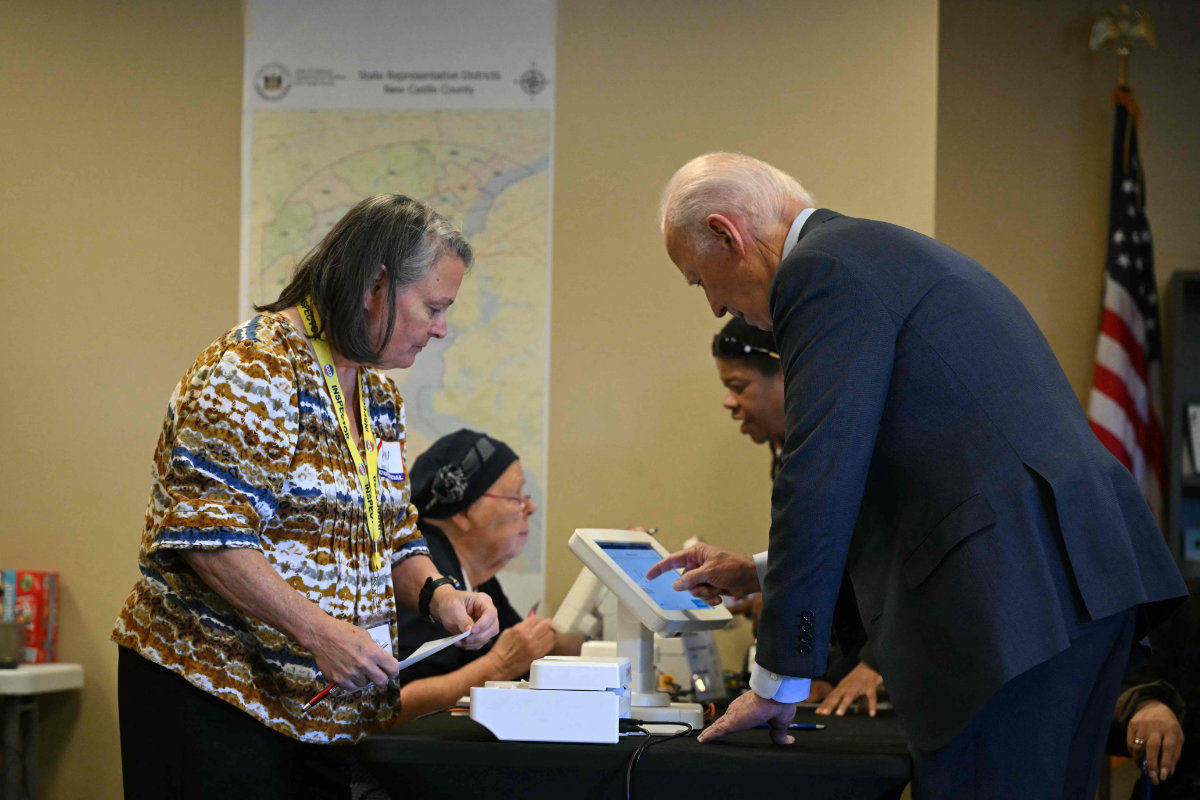

This year, early and mail-in voting are once again expected to play a crucial role, with millions of ballots already cast. President Biden voted early on Monday in his home state of Delaware.

US President Joe Biden casts his early-voting ballot in the 2024 general election in New Castle, Delaware, on October 28, 2024. (AFP)

States vary in how they handle mail-in ballots, with some processing them before election day and others waiting until polls close. In closely contested states, the volume of mail-in ballots could be a decisive factor, potentially delaying results.

Voting by mail has grown in popularity. According to ABC News, as of Tuesday, more than 25.6 million Americans have already returned mail ballots, and more than 65 million — including military personnel serving overseas — have requested absentee ballots.

In 2020, a comparable number voted by mail, though the COVID-19 pandemic significantly increased reliance on this option.

A voter casts her ballot during the early voting period on October 29, 2024 in the city of Dearborn in Michigan state. (Getty Images via AFP)

Despite its growing popularity, the mail-in voting system has faced accusations of fraud. During the last election, authorities and the postal service were strained by millions of extra ballots.

At the time, Trump said that mail-in voting was a “disaster” and “a whole big scam,” claiming that the Democrats had exploited the system to “steal” the election. The Democrats claim those allegations contributed to the Capitol Hill attack of Jan. 6, 2021.

This election cycle, some states, including Michigan and Nevada, have passed laws permitting early counting of mail-in ballots, which should lead to faster results. However, most states’ absentee voting policies have seen minimal changes, leaving tensions high.

Authorities are closely monitoring the process. In a sign of just how tense the situation has become, officials announced on Tuesday that they were searching for suspects after hundreds of votes deposited in two ballot drop boxes in the Pacific Northwest were destroyed by fire.

When will a winner be declared?

Indiana and Kentucky will be the first states to close their polls at 6 pm ET, followed by seven more states an hour later, including the battleground state of Georgia, which in 2020 voted for Biden. North Carolina, another critical swing state which picked Trump last time around, closes at 7:30 pm ET.

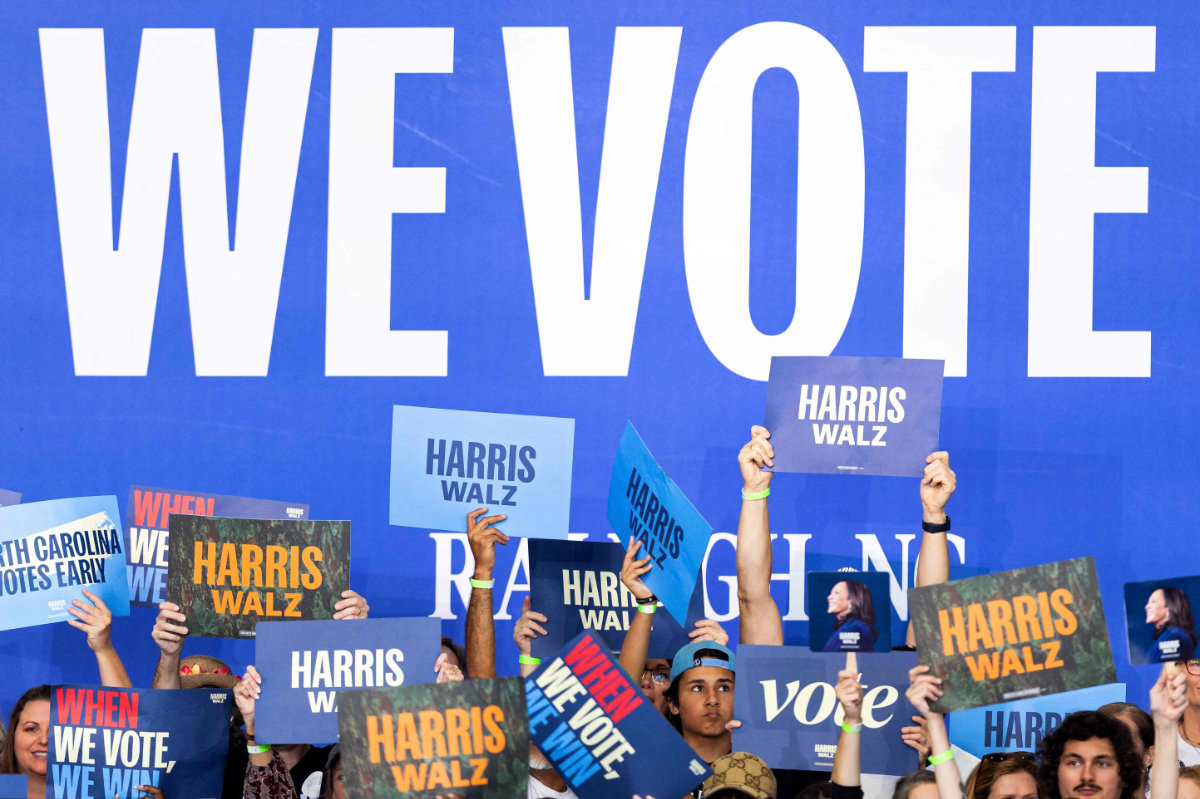

Supporters of US Vice President and Democratic presidential candidate Kamala Harris cheer during a Get Out the Vote rally in Raleigh, North Carolina, on Oct. 30, 2024. (AFP)

By around 8 p.m. ET, many states will have reported results, most of which are expected to follow traditional patterns. However, early results in solid Republican states like South Carolina could hint at trends in neighboring battlegrounds like Georgia.

By 9 p.m. ET, polls in key swing states such as Arizona, Wisconsin and Michigan close, with results trickling in soon after. By midnight ET, most of the nation will have reported, with Hawaii and Alaska closing shortly after, likely providing a clearer picture.

Pennsylvania, which is seen as a bellwether of the overall election outcome, aims to announce its results by early morning on Nov. 6.

The timing of a winner declaration ultimately depends on how close the race is in these key states. If one candidate establishes a clear lead in pivotal swing states early, a winner could be projected by major networks, as Fox News controversially did in 2020, calling Arizona for Biden hours ahead of other broadcasters.

Former US President and Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump dances as he leaves a campaign rally in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, on Oct. 30, 2024. (AFP)

If the race remains tight in crucial states like Pennsylvania, Arizona, or Michigan — all won by Biden last time around — the results may be delayed, possibly into the next day or later.

In 2020, it took four days to project Biden’s win due to a high volume of mail-in ballots. Experts caution that similarly close results this year could lead to a comparable delay.

Possible controversy

As in previous years, the outcome of the election will likely be contested. Delays in ballot counting, especially from mail-in votes, could fuel disputes in states where margins are tight.

Mail-in ballots are secured inside a cage before election day, as officials host a media tour of the Allegheny County election warehouse in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on Oct. 30, 2024. (AFP)

Both parties have prepared legal teams to challenge issues surrounding ballot validity, recounts, or other contested results.

Concerns over voter intimidation, misinformation and unsubstantiated allegations of fraud may further stoke tensions, despite the rigorous safeguards put in place.

In its latest assessment, the International Crisis Group noted that while conditions differ from 2020, political divisions remain sharp and risks of unrest remain high, especially if results are contested or take days to finalize.

As the world watches Tuesday’s election closely, there is widespread hope for a fair and peaceful process, marking a fitting conclusion to this tense political season.