KARACHI: Saghir Hussain Bhojani, a 76-year-old retired statistician, read out the Sindhi translation at his home in Karachi earlier this month as his teenage nephew Mashhood Shoaib Bhojani recited an Arabic verse from a handwritten copy of the Holy Qur’an.

This daily ritual serves not only as a spiritual practice for the Marwari family but also as a bridge to connect them with the Qur’an translation Bhojani’s grandfather, Abdul Latif Sultan Dino Bhojani, took over two decades to write by hand and complete in 1932.

“This [copy of] Holy Qur’an, which Allah has given us through our grandfather, is the greatest treasure for us,” Bhojani, the current custodian of the holy book, told Arab News about the handwritten Qur’anic copy with Sindhi translation.

The undate photo shows Abdul Latif Sultan Dino Bhojani (right) and Jawar Singh, the ruler of Jaislemere, India. (Saghir Hussain Bhojani)

Bhojani, whose family is Rajasthani-speaking, said he had received the copy from his mother who had gotten it from her father-in-law when she was 20.

“My father-in-law trusted me,” Zaitoon Bhojani, 95, told Arab News, recalling how Abdul Latif believed she would take care of the translation he had spent decades preparing and handed her the holy book in 1948, just months before he passed away on January 20, 1949, at age 65.

Saghir Hussain Bhojani (left), a 76-year-old retired statistician, shows hand-written Qur’an with Sindhi translation at his house in Karachi, Pakistan on October 6, 2024. (AN photo)

Zaitoon said her father-in-law sought help in preparing the book from a trunk-full of papers that he carried with him as he moved homes in the cities of Hyderabad, Rohri and finally Karachi, where the Silawat community from Jaisalmer in present day India settled after migrating for business to the region some two centuries ago.

Zaitoon preserved the Qur’an copy and made it a point to ensure her nine children, three daughters and six sons, read it regularly, but as she grew older, she decided to pass it on to her eldest son, Bhojani.

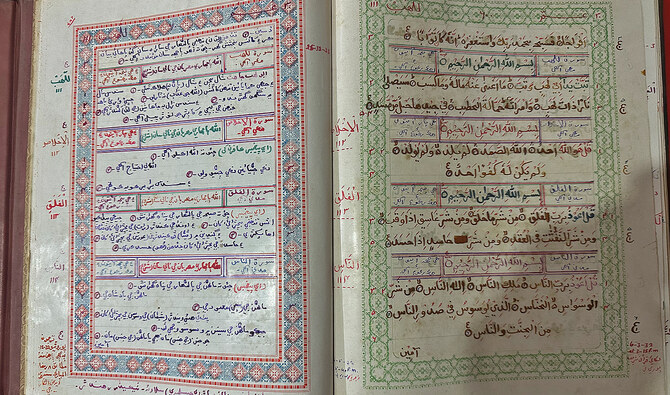

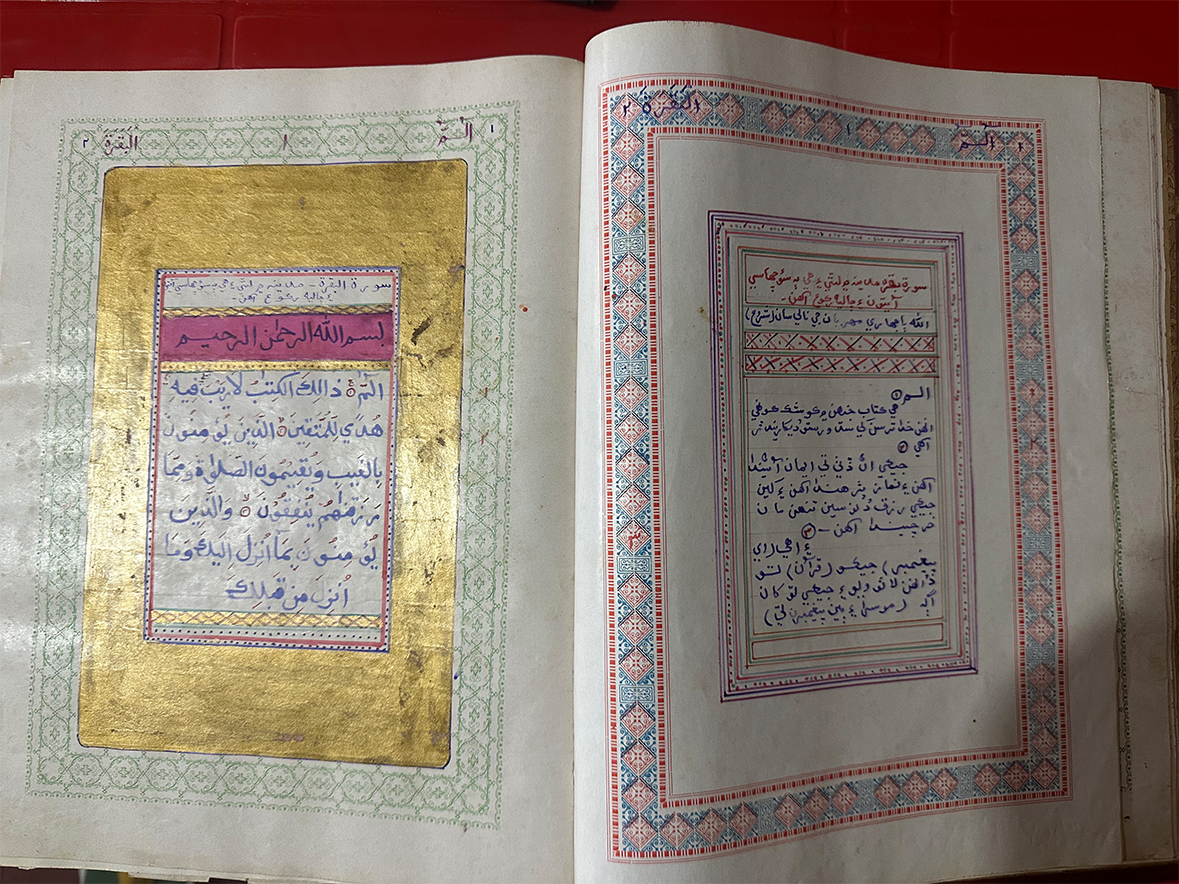

The picture taken on October 6, 2024, shows a hand-written copy of Holy Qur’an with Sindhi translation at Saghir Hussain Bhojani's, a 76-year-old retired statistician, house in Karachi, Pakistan. (AN photo)

“PRECIOUS INHERITANCE”

Born in 1886, Abdul Latif was the first Muslim mayor of Dadu district in Pakistan’s southern Sindh province and was elected chairman of the Kotri municipality several times. But being a close associate of Soreh Badshah, a champion of Hindu-Muslim unity and a freedom fighter executed by the British, cost him much of his property.

“We do not regret this loss because Allah has bestowed upon us a far more precious inheritance, the Holy Qur’an,” said Bhojani. “No matter how much we take pride in it, it is never enough.”

This photograph was taken during the return of Sayyid Sibghatullah Shah Al-Rashidi, popularly known as Soreh Badshah – a spiritual leader of the Hurs during the Indian independence movement, from Hajj in the early 1930s. Abdul Latif Sultan Dino Bhojani is seen fourth from the left in the front row. (Saghir Hussain Bhojani)

Abdul Latif spoke Marwari but chose to write in Sindhi for two reasons, according to his grandson: firstly, Marwari itself was not a formal language at the time, and secondly, he was far more proficient in Sindhi.

“He was the most prominent personality in Kotri,” Bhojani said, regretting that the Sindhi manuscript, a rarity at the time it was completed, was never printed.

“My parents were not very educated and didn’t have much understanding, which is why they couldn’t do it,” Bhojani, who retired as a Grade-18 chief statistician in Sindh, told Arab News.

The picture taken on October 6, 2024, shows hand-written copies of Holy Qur’an with Sindhi translation at Saghir Hussain Bhojani's house in Karachi, Pakistan. (AN photo)

“It’s also my own incompetence that I didn’t pay attention to [printing] it later ... It should be preserved and read the way my grandfather worked hard to prepare it.”

Bhojani’s nephew, Mashhood, an 18-year-old computer science student, said he would strive to continue the family tradition of reading from and preserving the inherited book.

“Our native language is Rajasthani and the [copy of] this Qur’an is in Sindhi,” he said as he took a brief pause from recitation.

“I still continue to read it with my uncle so that people like me remain in our family who can continue to read and understand it.”