STOCKHOLM: Swedish prosecutors said on Wednesday they would drop their investigation into explosions on the Nord Stream 1 and 2 gas pipelines and hand evidence uncovered in the probe over to German investigators.

“The conclusion of the investigation is that Swedish jurisdiction does not apply and that the investigation therefore should be closed,” the Swedish Prosecution Authority said in a statement.

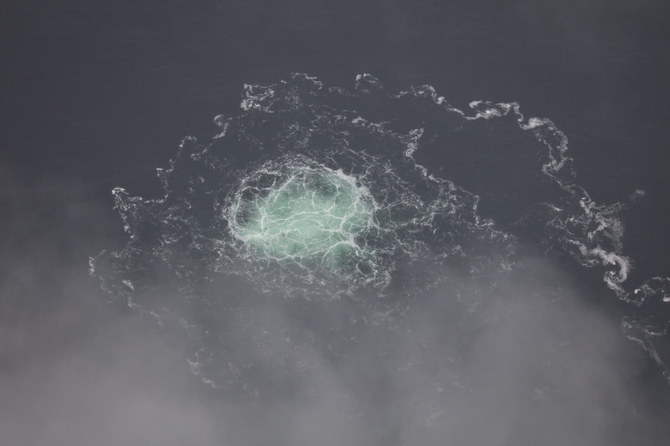

The multi-billion-dollar Nord Stream pipelines transporting Russian gas to Germany under the Baltic Sea were ruptured by a series of blasts in the Swedish and Danish economic zones in September 2022, releasing vast amounts of methane into the air.

Danish police have said the pipelines were hit by powerful explosions and Swedish investigators have confirmed that traces of explosives found on site conclusively showed that sabotage had taken place.

Sweden, Denmark and Germany launched separate investigations into the Nord Stream blasts, each tightly controlling information. The Danish and German probes are still ongoing.

“Within the framework of this legal cooperation, we have been able to hand over material that can be used as evidence in the German investigation,” the Swedish prosecution authority said.

Following an extensive investigation, the Swedish prosecutors concluded that nothing had emerged to indicate that Sweden or Swedish citizens were involved in the attack which took place “in international waters.”

“Against the background of the situation we now have, we can state that Swedish jurisdiction does not apply,” Public Prosecutor Mats Ljungqvist said in a statement.

Russia has blamed the United States, Britain, and Ukraine for the blasts which largely cut it off from the lucrative European market. Those countries have denied involvement.

If no conclusive evidence is found by either of the remaining investigations, the mystery behind one of the most significant acts of infrastructure sabotage in modern history could remain unsolved.

Sweden ends Nord Stream sabotage probe, hands evidence to Germany

Short Url

https://arab.news/zygva

Sweden ends Nord Stream sabotage probe, hands evidence to Germany

- Nord Stream pipelines transport Russian gas to Germany under the Baltic Sea

- Sweden, Denmark and Germany launched separate investigations into the blasts, each tightly controlling information

Neglected killer: kala-azar disease surges in Kenya

MANDERA: For nearly a year, repeated misdiagnoses of the deadly kala-azar disease left 60-year-old Harada Hussein Abdirahman’s health deteriorating, as an outbreak in Kenya’s arid regions claimed a record number of lives.

Kala-azar is spread by sandflies and is one of the most dangerous neglected tropical diseases, with a fatality rate of 95 percent if untreated, causing fever, weight loss, and enlargement of the spleen and liver.

Cases of kala-azar, also known as visceral leishmaniasis, have spiked in Kenya, from 1,575 in 2024 to 3,577 in 2025, according to the health ministry.

It is spreading to previously untouched regions and becoming endemic, driven by changing climatic conditions and expanding human settlements, say health officials, with millions potentially at risk of infection.

Abdirahman, a 60-year-old grandmother, was bitten while herding livestock in Mandera county in Kenya’s northeast, a hotspot for the parasite but with only three treatment facilities capable of treating the disease.

She was forced to rely on a local pharmacist who repeatedly misdiagnosed her with malaria and dengue fever for about a year.

“I thought I was dying,” she told AFP. “It is worse than all the diseases they thought I had.”

She was left with hearing problems after the harsh treatment to remove the toxins from her body.

East Africa generally accounts for more than two-thirds of global cases, according to the World Health Organization.

“Climate change is expanding the range of sandflies and increasing the risk of outbreaks in new areas,” said Dr. Cherinet Adera, a researcher at the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative in Nairobi.

- ‘So scared’ -

A surge in cases among migrant workers at a quarry site in Mandera last year led authorities to restrict movement at dusk and dawn when sandflies are most active.

At least two workers died, their colleagues said. Others returned to their villages and their fates are unknown.

“We did not know about the strange disease causing our colleagues to die,” said Evans Omondi, 34, who traveled hundreds of miles from western Kenya to work at the quarry.

“We were so scared,” added Peter Otieno, another worker from western Kenya, recalling how they watched their infected colleagues waste away day by day.

In 2023, the six most-affected African nations adopted a framework in Nairobi to eliminate the disease by 2030.

But there are “very few facilities in the country able to actively diagnose and treat,” kala-azar, Dr. Paul Kibati, tropical disease expert for health NGO Amref, told AFP.

He said more training is needed as mistakes in testing and treatment can be fatal.

The treatment can last up to 30 days and involves daily injections and often blood transfusions, costing as much as 100,000 Kenyan shillings ($775), excluding the cost of drugs, said Kibati, adding there is a need for “facilities to be adequately equipped.”

The sandfly commonly shelters in cracks in poorly plastered mud houses, anthills and soil fissures, multiplying during the rainy season after prolonged drought.

Northeastern Kenya, as well as neighboring regions in Ethiopia and Somalia, have experienced a devastating drought in recent months.

“Kala-azar affects mostly the poorest in our community,” Kibati said, exacerbated by malnutrition and weak immunity.

“We are expecting more cases when the rains start,” Kibati said.

Kala-azar is spread by sandflies and is one of the most dangerous neglected tropical diseases, with a fatality rate of 95 percent if untreated, causing fever, weight loss, and enlargement of the spleen and liver.

Cases of kala-azar, also known as visceral leishmaniasis, have spiked in Kenya, from 1,575 in 2024 to 3,577 in 2025, according to the health ministry.

It is spreading to previously untouched regions and becoming endemic, driven by changing climatic conditions and expanding human settlements, say health officials, with millions potentially at risk of infection.

Abdirahman, a 60-year-old grandmother, was bitten while herding livestock in Mandera county in Kenya’s northeast, a hotspot for the parasite but with only three treatment facilities capable of treating the disease.

She was forced to rely on a local pharmacist who repeatedly misdiagnosed her with malaria and dengue fever for about a year.

“I thought I was dying,” she told AFP. “It is worse than all the diseases they thought I had.”

She was left with hearing problems after the harsh treatment to remove the toxins from her body.

East Africa generally accounts for more than two-thirds of global cases, according to the World Health Organization.

“Climate change is expanding the range of sandflies and increasing the risk of outbreaks in new areas,” said Dr. Cherinet Adera, a researcher at the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative in Nairobi.

- ‘So scared’ -

A surge in cases among migrant workers at a quarry site in Mandera last year led authorities to restrict movement at dusk and dawn when sandflies are most active.

At least two workers died, their colleagues said. Others returned to their villages and their fates are unknown.

“We did not know about the strange disease causing our colleagues to die,” said Evans Omondi, 34, who traveled hundreds of miles from western Kenya to work at the quarry.

“We were so scared,” added Peter Otieno, another worker from western Kenya, recalling how they watched their infected colleagues waste away day by day.

In 2023, the six most-affected African nations adopted a framework in Nairobi to eliminate the disease by 2030.

But there are “very few facilities in the country able to actively diagnose and treat,” kala-azar, Dr. Paul Kibati, tropical disease expert for health NGO Amref, told AFP.

He said more training is needed as mistakes in testing and treatment can be fatal.

The treatment can last up to 30 days and involves daily injections and often blood transfusions, costing as much as 100,000 Kenyan shillings ($775), excluding the cost of drugs, said Kibati, adding there is a need for “facilities to be adequately equipped.”

The sandfly commonly shelters in cracks in poorly plastered mud houses, anthills and soil fissures, multiplying during the rainy season after prolonged drought.

Northeastern Kenya, as well as neighboring regions in Ethiopia and Somalia, have experienced a devastating drought in recent months.

“Kala-azar affects mostly the poorest in our community,” Kibati said, exacerbated by malnutrition and weak immunity.

“We are expecting more cases when the rains start,” Kibati said.

© 2026 SAUDI RESEARCH & PUBLISHING COMPANY, All Rights Reserved And subject to Terms of Use Agreement.