KARACHI: Sikandar Rind raised his binoculars to his eyes, observing a herd of ibex as it emerged on the foothills of the majestic Kirthar mountain range in Pakistan’s southern Sindh province.

Clad in the black uniform of the provincial wildlife department, Rind is among dozens of people deployed at the Kirthar National Park, established in 1974, to prevent illegal hunting of exotic animals.

From agile urials to chinkaras, wolves, jackals, and hyenas, thousands of mammals, reptiles and bird species call this natural haven home, creating a vibrant and diverse ecosystem.

“We work tirelessly, day and night, to protect and care for these animals,” Rind told Arab News. “This is why wherever you go, you see a multitude of animals.”

The guards, or game watchers, move around all day and night, carrying food and water with them so they can always be on the job in the park spanning over 1,192 square miles and stretching across the districts of Jamshoro and Malir.

"We work hard day and night to look after and protect them [animals] ... we have all the things we need for tea and food with us, we make arrangements for rations also and ensure that we carry enough water with us so that it doesn't run out anywhere," Rind said.

In this photo, posted on August 5, 2023, vehicles carrying visitors drive at dusk in Kirthar National Park in Pakistan’s southern Sindh province. (Photo courtesy: Facebook/KirtharNationalPark)

A comprehensive survey conducted about 23 years ago by the University of Melbourne in collaboration with the Sindh administration and the Zoological Survey Department uncovered a total of 277 vertebrate species in the area. Among them were 203 avian, 37 mammal, 34 reptile, and three amphibian species.

This picture taken from the Kirthar National Park baseline study document on June 1, 2023, shows a milestone of the British period indicating 88 miles from Karachi. Kirthar had been a hunting ground during Talpur and British rule of the region, wildlife officials say. (Photo courtesy: Sindh Wildlife Department)

The survey results also helped identify six bird and eight mammal types as endangered animal classes.

“No survey has been conducted since then, so we can’t determine the current numbers,” Javed Mehar, the top official at the Sindh Wildlife Department, told Arab News.

“However, the survey conducted in the buffer and game zone reveals sustainability, as we have consistently observed a similar number of animals since 2000.”

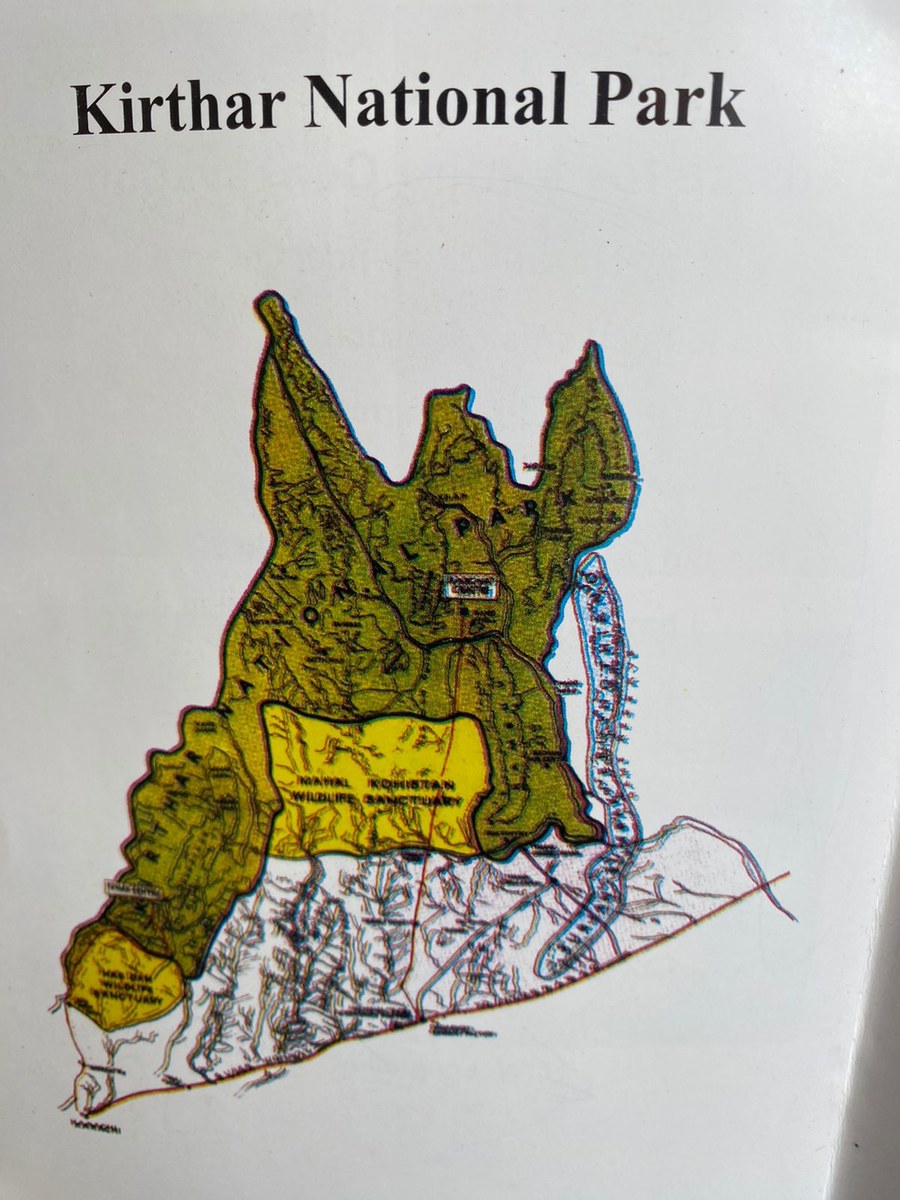

The picture taken from a book on May 30, 2023, 2023 shows a map of Kirthar National Park. (AN photo)

Wajid Shaikh, another wildlife department official, said there had been an increase in animals in the area after Kirthar was declared a national park.

“Prior to that, there were very few animals left, they were almost nonexistent. Being a protected area, the number of animals has significantly increased,” he told Arab News, explaining that the park has a protected area, buffer zone, and game reserve.

Authorities also offered limited hunting permits for the game reserve, Shaikh said.

Before being declared a national park, community members living in the area said it was a reckless hunting ground.

“Hunting took place openly,” said Yar Muhammad Burfat, a teacher and historian whose ancestors have lived in the same area for centuries.

Shaikh, the wildlife official, acknowledged the role of the local community in protecting the animals.

“The role of the community in protecting animals has increased since the inception of the trophy hunting program,” he said, adding that 80 percent of the money generated by implementing the initiative went to locals:

“We provide 15 ibexes and five urials to foreigners. We also allocate five animals to Pakistanis.”

Pir Muhammad Bux, a 78-year-old resident of the area who once patrolled the park with other community members, said the people of Kirthar deserved appreciation.

“All these game watchers protect the animals,” he said. “In general, everyone here, whether young or old, are always thinking about how to save these animals from [illegal] hunting.”