PESHAWAR: Paintings made by street children in the northwestern Pakistani town of Peshawar were displayed in an exhibition held by the Rangeet Welfare Organization (RWO) on Tuesday, coinciding with International Education Day, which is marked on January 24 each year.

Estimates suggest there are over two million street children in Pakistan – a number increasing rapidly due to displacement, migration, extreme poverty, and the rising numbers of runaway children forced to leave their homes after experiencing violence in the household, workplace and schools. Once on the streets, these children are at greater risk of being drawn into situations of abuse, such as child labor, exploitation, trafficking, and arbitrary arrest.

In August 2021, Jalwat Huma, a Peshawar resident, established RWO in the basement of her home to teach street kids how to use art as a means of creative expression under the slogan, “If you can’t write, you can still draw.”

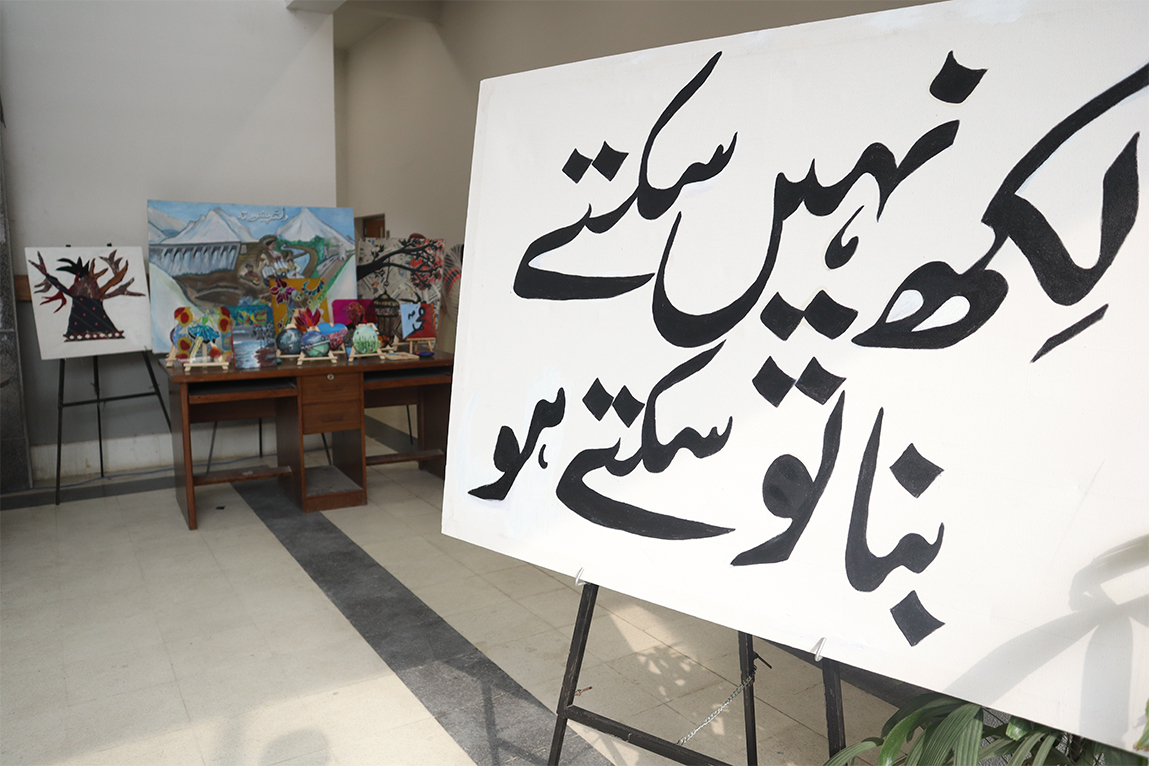

"If you can't write, you can still draw," says an inscription in Urdu at a painting exhibition by street children in Peshawar, Pakistan, on January 24, 2023. (AN Photo)

On Tuesday, RWO organized an exhibition at the Peshawar University which held true to the old adage, “paint what you see,” showcasing canvases full of depictions of the alienated and the marginalized: homeless people, women and children begging on the streets, worried mothers, hands on their foreheads, cradling their newborns, as well as mosques, clerics and women in traditional tribal attire.

“We arranged this exhibition keeping in mind International Education Day so that these [underprivileged] children could celebrate the day too,” Huma told Arab News at the event. “The work of street kids – whom I consider very special – has been put up for public display which is an immense pleasure for me.”

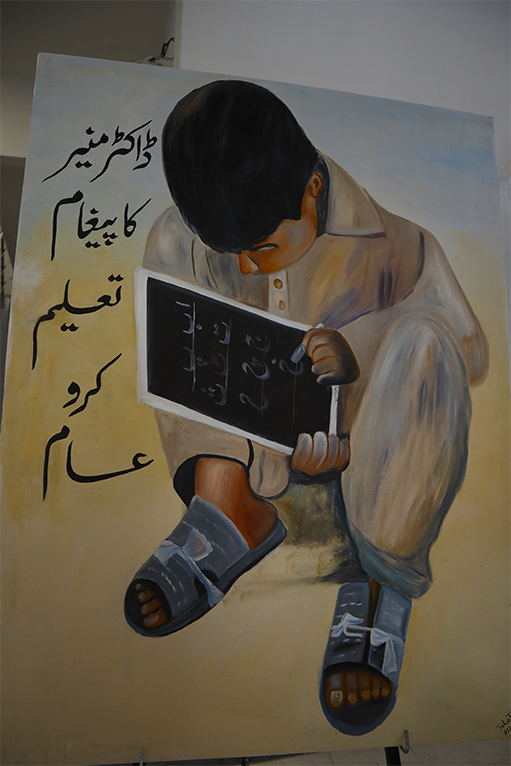

A painting by a street kid showing vulnerable children is displayed at an exhibition in Peshawar, Pakistan, on January 24, 2023. (AN Photo)

“Just over a year ago, I initiated this journey with underprivileged children, impoverished and left to fend for themselves, sell what they scavenge off the streets or work mornings in other people’s homes. Now I am proud to display their work here in front of you all.”

Paintings by street children are displayed at an exhibition in Peshawar, Pakistan, on January 24, 2023. (AN Photo)

Huma said working with street children was a difficult task because they didn’t have any formal schooling or education in the arts, but the effort they put into their work was refreshing: “We aim to make these children international level artists and want to display their work in an international exhibition in future.”

She said her organization was also teaching them English, computers and music.

A painting by a street child that highlights the significance of education is displayed at an exhibition in Peshawar, Pakistan, on January 24, 2023. (AN Photo)

The majority of the 106 students in RWO are from the tribal Khyber region, adjacent to Peshawar district.

“Painting is an expensive medium and we couldn’t afford a huge number of students at this stage,” Huma said. “However, we have 106 children enrolled so far out of whom the works of 27 children have been displayed in this exhibition.”

Dozens of people attend a painting exhibition by street children in Peshawar, Pakistan, which was made to coincide with International Education Day on January 24, 2023. (AN Photo)

The children Arab News spoke to said they were “happy” to see their work on display and being appreciated by people from different backgrounds.

Abdullah Afridi, originally from Bara village in Khyber, said he had worked in a medicine company as an errand boy before he joined RWO a year ago and started learning how to paint:

“A friend in my neighborhood informed me that there is a place where people like me learn painting, so I visited there. After seeing people like me painting and drawing I got the motivation and left the factory and joined RWO.”

“I feel very happy when I’m painting,” Afridi said. “I was doing other people’s labor for very little pay before, now I do my own work. In the future I want to become a famous artist and portray the grief of people like me, and maybe help them like Madam Huma helped me.”

A student at Rangeet Welfare Organization, which has been working to educate street children, stands next to a painting at an exhibition in Peshawar, Pakistan, on January 24, 2023. (AN Photo)

Shahab Orakzai, a teenage volunteer at RWO who helps the children with final touch-ups and finishes on their paintings, said: “This is a great achievement for all of us. All these months we worked so hard with these street children.”

“This is a dream come true. In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, we don’t see such things. It is a proud moment that the work of street children is being displayed and people are appreciating it.”

A painting that depicts Pashtun women from different parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province is displayed at an exhibition by street children in Peshawar, Pakistan, on January 24, 2023. (AN Photo)

Hundreds of people from different walks of life, especially students, teachers, and art lovers, visited Tuesday’s exhibition and appreciated the efforts of kids less fortunate than themselves.

“Here I see paintings done by poor children, who sometimes scavenge, sometimes beg,” Warda Hussain, who had especially come to see the exhibition, told Arab News. “Still, they’re doing a great job, their paintings are amazing.”

A painting by a street child that captures life on social peripheries is displayed at an exhibition in Peshawar, Pakistan, on January 24, 2023. (AN Photo)