Huthaifa Hejazi is hosting Riyadh’s first gathering for public life drawing during Misk Art Week’s sixth edition, which launched on Wednesday.

An interior designer and an artist, Hejazi, 33, was invited by Misk Art Institute to supervise a group of aspiring Saudi and foreign artists focused on life drawing.

The classes or “gatherings,” as termed by Misk Art Institute, are the result of an informal community in Riyadh that practiced life drawing together until they found Masaha Residency in Prince Faisal bin Fahd Arts Hall, the home of Misk Art Institute in Riyadh, where they have been gathering weekly since August this year. The staging of such life drawing gatherings publicly, which have until this week been practiced privately in the Kingdom, further exemplifies changing times in Saudi Arabia.

“It is a big step for us to host live painting and drawing here, and I am trying to do everything I can to support the community,” Hejazi told Arab News.

“This is a new experience for us; life drawing helps you better your skills,” said Mansour Alotaibi, an engineer who works at the Ministry of Energy and has been painting since he was a child.

The life drawing and painting gatherings are one of the most popular events taking place during Misk Art Week, which ends on Dec. 10. They are free and open to the public, like all activities taking place during the event.

This year marked the most dynamic and comprehensive edition for Misk Art Institute’s flagship event, witnessed through a sprawling array of art exhibitions, and a range of talks and workshops reflective of the organization’s mission to strengthen the local and regional creative community. The art week, also, as Mashael Al-Yahya, creative director at Misk Art Institute, said, marks the full return of the event after the COVID-19 pandemic.

“This edition, in its scale, is similar to that which was hosted in 2019,” Al-Yahya told Arab News. “But because of COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021, we needed to downsize. We fully brought back our programming to this year’s art week, largely witnessed in the Art and Design Market that used to be called the Artist Street.”

A range of white cube open-air spaces in various heights made up the Art and Design Market, providing free booths to 81 creatives from across the Kingdom based on an open-call process. Works on show spanned the realms of ceramics, painting, accessories and jewelry. Like a mini art fair, guests could acquire, source and commission one-off works.

Abeer Al-Zayed, an artist from Al-Baha, came to Riyadh to show her paintings featuring delicate and colorful portraits of anonymous women at the Art and Design Market, marking her fifth time taking part in a Misk event. “We are witnessing the growth of the art scene in Saudi Arabia, and this makes me very happy,” she told Arab News.

Other highlights included the two-day Creative Forum, which brought in top speakers on art and culture from around the Middle East and internationally. Artists include Emirati Sultan Sooud Al-Qassemi, founder of Barjeel Art Foundation; Dr. Nada Shabout, regent professor of art history and coordinator of the Contemporary Arab and Muslim Cultural Studies Initiative at the University of North Texas, and artists such as pioneering Saudi woman Safeya Binzagr.

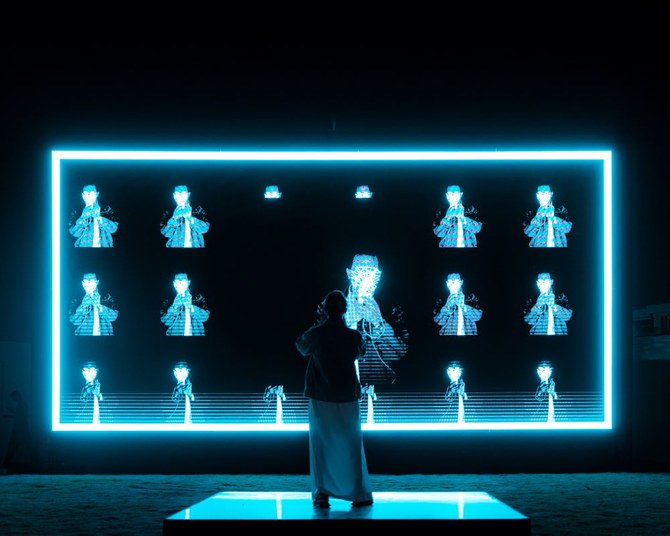

On the second floor of the Prince Faisal bin Fahad Arts Hall was the third edition of the Misk Art Grant, one of the most sought-after grants in the region with a fund of SR1 million ($266,632) distributed among three to 10 artists and collectives from across the Arab world. In a tightly curated show, the artists showcased their work, made this year according to the theme of Saraab, which means mirage in Arabic. Noteworthy was how the works examined the relationship between movement, memory and ideas pertaining to what is visible and invisible.

This year’s recipients included Saudi artists Abdulmohsen Albinali and Juri Alfadhel; M’hammed Kilito from Ukraine, Athoub Al-Busaily from Kuwait, and Rawdha Al-Ketbi and Zeinab Alhashemi from the UAE.

Alhashemi presented “The Grid,” a powerful series of six steel beam sculptures recreating the cylinder pipes found in Prince Faisal bin Fahd Fine Arts Hall. The gold and black cylinders, some standing tall and erect while others curving over, featured black claps on the interlocking beams, making the piece almost akin to jewelry pieces. They are, emphasized the artist, an attempt to play on the visibility and invisibility of the pipes, almost as if to say that the objects surrounding us are more prominent and crucial than we might think.

“Cylinders don’t seem to be invisible, but when people are looking at the art, they don’t seem to notice them or they act like they don’t see them in a way,” Alhashemi told Arab News.

“I wanted to dive deeper into the meanings behind the grids and also how different artists have used them in the past like Agnes Martin,” she added.

“To her, the grid was very meditative, and it was a way of applying some sort of harmony to her horizontal and vertical lines,” she said.

As visitors come and go from the venue, they pass the exhibition Azeema, which means “invitation” or “getting together” in Arabic. Inside are works by a range of Gulf or Khaleeji creatives reflecting on hospitality’s historical and cultural importance in the region. Videos, installations, photography and paintings showcase the persistence of collective gatherings, sharing and shared memories. On show are pivotal works such as Saudi artist Filwa Nazer’s “The Family Series,” dating to 2015, featuring cutouts superimposed over the artist’s family portraits.

There are images of weddings by acclaimed Saudi photographer Tasmeen Alsultan, paintings by Emirati artist Khalid Al-Banna — his vibrant mix of paint on his colorful abstract canvases is akin to a dynamic social gathering — and Elham Aldawsari’s photographs titled “Subabat” (2020) capture her research into the history of Saudi women hospitality workers.

Aldawsari’s large photographs greet visitors at the entrance just as a subabat — women who serve drinks and food at all-women events — would do. The artist, who grew up during the 1990s during a time when the internet was not readily available in the Kingdom, showcases the memories and stories of these women who have watched, through their personal and professional lives, while always serving others, the myriad changes that have shaped their country over the last few decades.