AMMAN: From Greco-Roman times, the Dead Sea’s unique equilibrium was finely balanced by nature. Fresh water from nearby rivers and springs flowed into the lake, combining with rich salt deposits and then evaporating, leaving behind a brine of 33 percent salinity.

Now, owing to a combination of climatic and man-made factors, this balance has been disrupted. As a result, the Dead Sea has been receding at an alarming rate over the past half century, endangering its very existence.

The Dead Sea has been receding at an alarming rate over the past half century. (AFP)

At the UN Climate Change Conference, COP27, held in Egypt’s resort town of Sharm El-Sheikh in November, a joint Israeli-Jordanian agreement was signed to try to address the Dead Sea’s decline.

However, given that the deal excluded the Palestinians and was signed by an outgoing Israeli environment ministry official, some say that its chances of success are low.

Without sufficient funding, and in the absence of a three-way agreement, Jordan and Israel have instead decided to focus on cleaning up the Jordan River to help replenish the Dead Sea’s main water source.

What was signed by Israeli and Jordanian officials on the sidelines of COP27 was an agreement to this effect. But if the Dead Sea is to be rescued from impending oblivion, it is clear that far more needs to be done to undo the damage to its natural freshwater sources and to set aside political rivalries for the common environmental good.

No one knows exactly how the Dead Sea came into being. The Bible and other religious texts suggest this lifeless, salty lake at the lowest point on Earth was created when God rained down fire and brimstone on the sinful towns of Sodom and Gomorrah.

Russian experts have even tried excavating under the lake bed in the hope of finding evidence to support the Biblical tale. A nearby religious site called Lot’s Cave is said to be where the nephew of Abraham and his daughters lived after fleeing the destruction.

Scientists, meanwhile, point to the lake’s more mundane, geological origins, claiming the Dead Sea is the product of the same tectonic shifts that formed the Afro-Arabian Rift Valley millions of years ago.

Halfway through the 20th century, among the first big decisions made by the newly formed state of Israel was to divert large amounts of water by pipelines from the Jordan River to the southern Negev, in order to realize the dream of Israel’s first prime minister David Ben-Gurion to “make the desert bloom.”

If the Dead Sea is to be rescued from impending oblivion, it is clear that far more needs to be done to undo the damage to its natural freshwater. (AFP)

In 1964, Israel’s Mekorot National Water Company inaugurated its National Water Carrier project, which gave the Degania Dam — completed in the early 1930s — a new purpose: to regulate the water flow from the Sea of Galilee to the Jordan River.

One result was that the share of water reaching the neighboring Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan fell drastically, thereby depriving the Dead Sea of millions of cubic meters of freshwater per year from its primary source.

Another potential contributing factor at present is the Israeli company behind Ein Gedi Mineral Water. The Ein Gedi bottling plant has monopolized the use of freshwater from a spring that lies within the 1948 borders of the state of Israel and which long fed into the Dead Sea.

However, not all the blame for the lake’s decline rests with one country. According to Elias Salameh, a water science professor at the University of Jordan, every country in the region bears some responsibility.

“All of us are responsible at different levels for what has happened to the Dead Sea,” Salameh told Arab News. Israel, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria have all sucked up water intended for the Dead Sea in order to satisfy their own needs.

FASTFACTS

• The Dead Sea receives almost all its water from the Jordan River.

• It is the lowest body of water on the surface of the planet.

• In the mid-20th century, it was 400 meters below sea level.

• By the mid-2010s, it had fallen to 430 meters below sea level.

In 1955, the Jordan Valley Unified Water Plan, brokered by US Ambassador Eric Johnston, allowed Israel to use 25 million cubic meters of Yarmouk River water per year, Syria 90 million and Jordan 375 million.

“But not all countries abided by the commitments made to the American, Johnston,” said Salameh. “It was never signed because Arab countries had not recognized Israel and refused to sign any agreement with Israel. Syria took the biggest portion, getting away with 260-280 million cubic meters annually.”

In the 1970s, Jordan and Syria began their own diversion of the Yarmouk River, the largest tributary of the Jordan River, again reducing its flow. Another agreement, in 1986, gave Jordan the right to 200 million cubic meters. But, in reality, Jordan took barely 20 million.

According to the UN, Jordan is the second most water-scarce country in the world. The 1948 and 1967 Arab-Israeli wars, which led to the mass exodus of Palestinians, more than doubled Jordan’s population, making its water needs even more acute.

As a result of these deals and diversions, the Dead Sea receded from roughly 398 meters below sea level in 1976 to around 430 meters below sea level in 2015. What is more worrying, perhaps, is the decline has been accelerating.

“Climate change has aggressively hit Jordan in the past two years,” said Motasem Saidan, University of Jordan professor. (Supplied)

During the first 20 years after 1976, the water level dropped by an average of six meters per decade. Over the next decade, from the mid-1990s to the early 2000s, it fell by nine meters. In the decade up to 2015, it fell by 11 meters.

Some attribute this accelerating decline to man-made climate change. Climate scientists say global warming has already resulted in significant alterations to human and natural systems, one of which is increased rate of evaporation from water bodies.

At the same time, the waters of the Dead Sea are not being replenished fast enough.

Although the Dead Sea borders Jordan, Israel and Palestine, and despite the valiant efforts of such cross-border NGOs as Earth Peace, which includes activists from all three communities, no serious collective action has been taken to deal with the ecological disaster.

Cooperation is essential, however, to stave off the wider environmental consequences — most concerning of all being the rapid proliferation of sinkholes along the Dead Sea shoreline.

According to scientists, when freshwater diffuses beneath the surface of the newly exposed shoreline, it slowly dissolves the large underground salt deposits until the earth above collapses without warning.

Over a thousand sinkholes have appeared in the past 15 years alone, swallowing buildings, a portion of road, and date-palm plantations, mostly on the northwest coast. Environmental experts believe Israeli hotels along the shoreline are now in danger.

On the Jordanian side, too, the fate of luxury tourism resorts along the eastern shore of the Dead Sea face is in the balance.

Dead Sea is the product of the same tectonic shifts that formed the Afro-Arabian Rift Valley millions of years ago, scientists say. (AFP)

“The main highway, which is the artery to all the big Jordanian hotels, is in danger of collapsing if the situation is not rectified,” Salameh said.

Israel has developed a system that can predict where the next sinkhole will appear, based on imagery provided by a satellite operated by the Italian Space Agency, which passes over the Dead Sea every 16 days and produces a radar image of the area.

By comparing sets of images, even minimal changes in the topography can be identified before any major collapse.

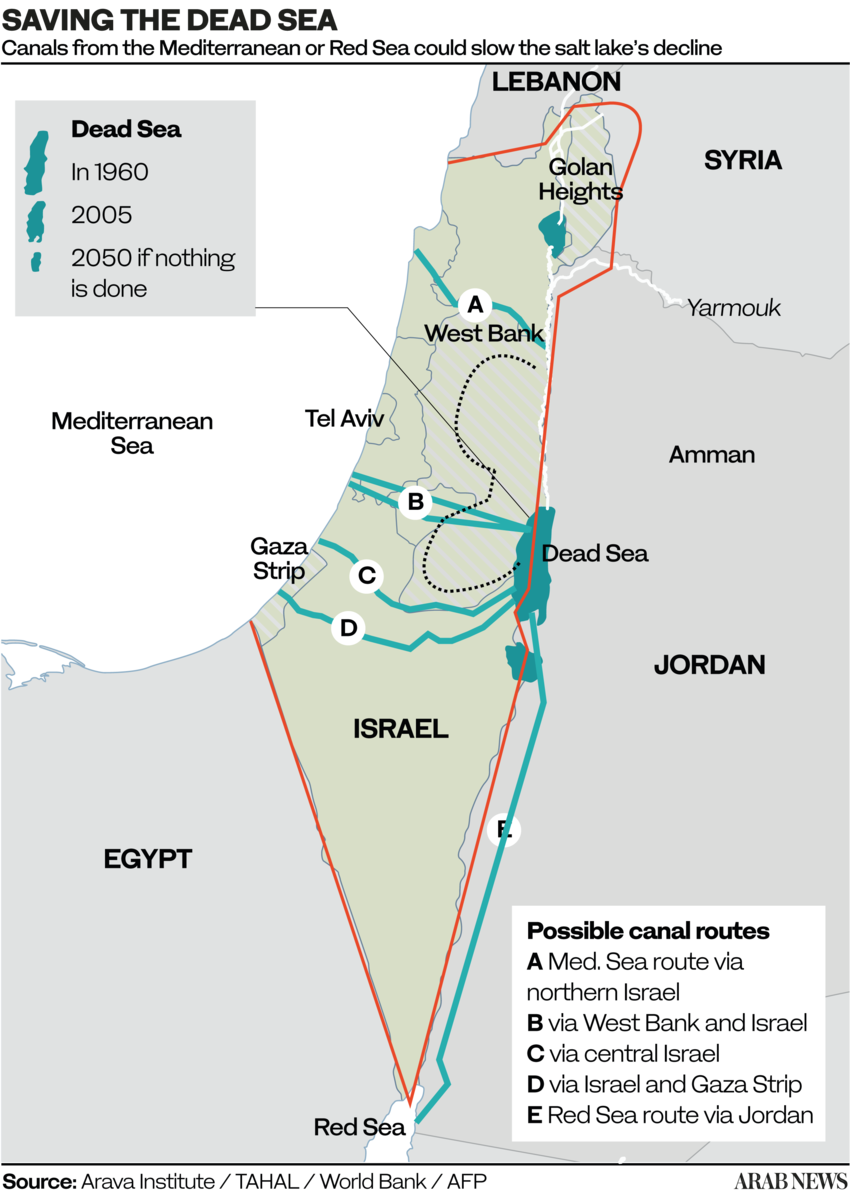

Israeli officials have been searching for solutions to prevent a further decline in water levels and thereby stave off the spread of sinkholes. One suggestion is the construction of a Red Sea-Dead Sea canal.

A report compiled to assess the potential impact of transferring Red Sea water into the lower-lying Dead Sea found that a moderate flow could slow, but not halt, the retreat of the Dead Sea and reduce the number of new sinkholes per year.

Ironically, it found that too much Red Sea water could have the opposite effect. If the flow was significant enough to raise the level of the Dead Sea, the report predicted the sinkhole problem would be exacerbated.

Because the Red Sea is less salty than the Dead Sea, it would likely increase the dissolution of underground salt deposits and thereby speed up the appearance of sinkholes.

Although many solutions have been suggested to help address the Dead Sea’s decline, none has been implemented owing in large part to a lack of funding.

The Dead Sea receded from roughly 398 meters below sea level in 1976 to around 430 meters below sea level in 2015. What is more worrying, perhaps, is the decline has been accelerating. (AFP)

According to Salameh, the most logical solution proposed to date is the Med-Dead project, which would allow for a channel to run from the Mediterranean Sea to the Dead Sea.

Two of the sites proposed for this channel are Qatif, near the Gaza Strip, and Bisan, north of the Jordan River in Jordan. However, such a plan would first require Jordanian and Palestinian approvals.

Jordan has also suggested a similar project establishing a channel from the Red Sea, but Salameh does not consider this feasible.

“The distance is long, and it is not a viable project,” he said.