ISLAMABAD: Pakistan resumed its anti-polio immunization drive on Monday, its third this year, to vaccinate 33.6 million children under five in 124 districts across the country and Azad Kashmir.

Anti-polio drives have been disrupted due to security reasons in the past, and most recently, by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the latest initiative, around 223,000 polio workers will visit people’s homes while adhering to strict COVID-19 protocols, including wearing a mask, using a hand sanitiser, and maintaining a safe distance during the vaccination drive.

“To make this campaign successful, cooperate with frontline health workers,” Dr. Shahzad Baig, a coordinator for the End Polio Program (EPP), an offshoot of the health ministry’s Pakistan Polio Eradication Program (PPEP), said in a statement on Monday.

Pakistan and Afghanistan are the two countries where polio — a disabling and life-threatening disease caused by the poliovirus — is endemic.

Health officials said the PPEP campaign has been highly successful this year, with only two polio cases reported, a sizeable drop from the 84 cases documented in 2020.

Last month, Health Minister Dr. Faisal Sultan said that despite the “complex challenges” posed by the COVID 19 pandemic,” authorities were “optimistic about controlling polio before the end of 2022.”

He cited recent epidemiological data which showed a drop in polio cases, adding: “Decreased detection of viruses in sewage samples indicates the program is on track.

Polio is a highly infectious disease mainly affecting children under the age of five years. It invades the nervous system and can cause paralysis or even death. While there is no cure for polio, vaccination is the most effective way to protect children from the disease.

In a separate statement released on Monday, the PPEP encouraged parents to immunize all children under five against the disease.

“Each time a child under the age of five is vaccinated, their protection against the virus is increased. Repeated immunizations have protected millions of children from polio, allowing almost all countries in the world to become polio-free,” it said.

Third anti-polio drive this year launched to immunize over 33 million Pakistani children

https://arab.news/jvzty

Third anti-polio drive this year launched to immunize over 33 million Pakistani children

- More than 220,000 polio workers will target 124 districts across the country while adhering to strict COVID-19 protocols

- Nationwide program “on track,” health chief says with only two polio cases reported this year

Against all odds, Pakistani youth with cerebral palsy bags gold medal in master’s program

- Pakistan has a population of 7.4 million persons with disabilities, official data states, who face barriers to economic and social opportunities

- An overwhelming majority of special education institutes are critically understaffed, lack non-teaching support personnel and essential specialists

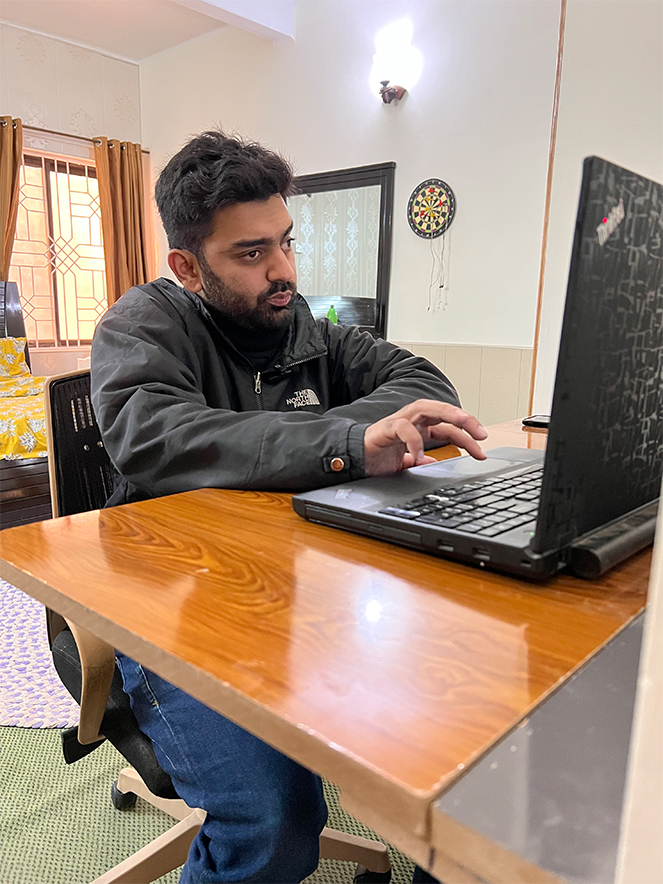

TALAGANG: Maaz bin Majid walked toward his laptop in his bedroom in the eastern city of Talagang, moving slowly as he navigated the usual stiffness in his muscles. He turned it on and began surfing websites for scholarship opportunities to continue his studies.

Born with cerebral palsy, a neurological condition affecting muscle coordination and movement, the 25-year-old earned the gold medal in his master’s degree in Special Education from Allama Iqbal Open University (AIOU).

The news of his winning the gold medal came as a “shock” to both Majid and his mother, Nighat Malik, after the university informed them of his achievement.

“For three days, I was in complete shock,” Majid told Arab News. “When a person has a problem and he suddenly finds out that he is getting a gold medal.”

According to the 2023 census, Pakistan has 7.4 million persons with disabilities, though independent organizations say the number is likely higher. They often face barriers in education, economic participation, legal recognition, and access to clinical resources.

In Islamabad, there are 73,022 persons with disabilities, including 6,304 school-age children. Yet only 1,900 students are enrolled across five public-sector special education institutes, a mere 30 percent.

The education ministry, which took charge of these institutes from the Ministry of Human Rights in June 2024, reports that 85.7 percent are critically understaffed, 100 percent lack non-teaching support personnel, and 85.7 percent lack essential specialists such as psychologists, speech therapists, and audiologists.

The federal government claims it is addressing these gaps. Contracts have been awarded for upgrades to special education institutions in Islamabad. A project to equip university students with special needs has been added to the Public Sector Development Programme (PSDP) for 2025-26.

“It’s a Rs1.8 billion [$6.4 million] project where electric wheelchairs, computers with braille technology, and other assistive devices will be provided to students in various universities across Pakistan,” Federal Secretary of Education Nadeem Mahbub told Arab News.

Punjab, Pakistan’s most populous province, is home to 1.73 million children with disabilities, aged 5 to 17. According to “Pakistan Education Statistics,” a 2023-24 report by the federal education ministry, Punjab operates 293 special education institutes serving 38,478 students. In contrast, Sindh enrolls 4,283 students across 65 institutes, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) serves 432 students in three institutes, and Balochistan has 891 students across 16 facilities.

Dr. Hina Noor, head of AIOU’s Special Education Department, acknowledged Punjab’s relative progress compared to other provinces.

“They (KP, Sindh and Balochistan) have not been able to do as much progress as Punjab has done,” she said.

In its 2021-22 report, the federal education ministry noted that Punjab allocates the highest budget and share for special education, followed by other provinces.

While it indicates recognition of the importance of special education in the country’s most populous province, the infrastructure gap extends beyond the school level.

A recent survey by Dr. Noor’s department found that across all of Punjab, only a little over 100 students with special needs are enrolled in higher education programs.

In 2021, Pakistan’s Higher Education Commission introduced a policy requiring universities to reserve at least one seat for students with disabilities.

“With these directives, accessibility and enrollment will increase in the future,” Dr. Noor said, stressing that teachers need training to educate students with disabilities, using adapted methods rather than the same curriculum applied to all students.

‘PROBLEM WITH MYSELF’

Malik knows the stigma attached to her son’s condition. When she first took Majid to a private hospital in Islamabad, a doctor said he would “never be able to do anything,” suggesting that at best he might learn to care for himself. The mother paused treatment for six months but later sought a second opinion in Lahore, where doctors reassured her that physiotherapy could help him improve significantly.

Watching her son navigate a system not designed for him, Malik pursued a master’s degree in Special Education and is now a principal at a government-run school in Chakwal where she applies those lessons to help other families.

“I wanted to tell [others] how difficult it is for parents to have a special child,” she said.

Majid was first enrolled in a mainstream school in Talagang, where the administration and fellow students facilitated his early education. But during 10th grade, a medical treatment intended to improve his condition backfired dramatically, according to his mother.

He spent weeks recovering, struggling to speak or perform basic daily activities. The medical treatment eventually restored his mobility and speech, but the aftermath left his facial muscles weakened and his writing ability severely compromised.

Malik said her son, who required scribes to write in examinations and relied on the AIOU’s distance learning program to avoid the challenges of regular travel after intermediate, had a relentless study routine: waking up early, studying throughout the day, with no time for entertainment.

For Majid, choosing the same field as his mother came from first-hand experience of the challenges.

“Because I have a problem with myself, I thought that I should do something for other special kids as well,” he added.