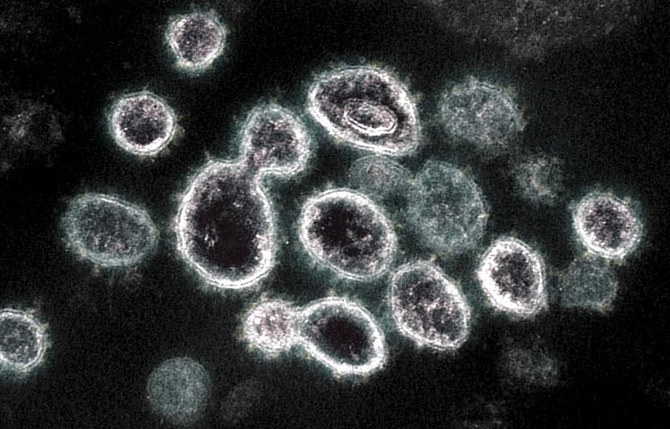

LONDON: Humanity is engaged in an “arms race” with the coronavirus Sars-CoV-2, and its capacity to adapt and evolve remains unknown and should not be underestimated, scientists have warned.

“I think it’d be a brave person to say that the virus is nearing the end of its evolutionary route and can’t go any further,” Prof. Deenan Pillay, a virologist at University College London, told The Independent.

“We’re still early on in the lifetime of this virus as a human pathogen. It normally takes many years for viruses, once they cross the species barrier, to really optimize themselves to be able to replicate well within humans.”

Pillay’s warning comes amid fears that a new strain of Sars-CoV-2, known as the India variant — which has caused a surge in the number of cases of COVID-19 — could become a dominant global strain in the coming weeks.

The India variant is known to carry two mutations that could reduce the efficacy of a number of COVID-19 vaccines.

Whilst that has not yet occurred, the nature and speed at which the virus has mutated thus far, including in the form of the South African and UK variants, has caused alarm among the scientific community that the positive impact of vaccine rollouts could be undone in the near future.

Specifically, scientists worry about Sars-CoV-2’s ability to alter spike proteins, used to attach onto human cells, through mutations.

The spike proteins, referred to by Pillay as “keys” to entering human receptor cells, are the mechanism through which most of the world’s successful COVID-19 vaccines look to attack the virus, by training various immune system responses to identify them.

One such mutation, E484K, has been found in the South Africa and UK variants. The India variant carries a similar mutation, E484Q.

The fear is that by altering their proteins, these variants could render them less visible to the immune system of vaccinated people, making it harder to ward off infection.

Aris Katzourakis, professor of evolution and genomics at Oxford University, said beyond altering the spike protein, mutations such as E484K could “unlock a whole load of other mutations elsewhere in the spike” that have not yet been identified by scientists, with unknown repercussions for the severity of the virus.

“E484K took about 12 months before it became something we cared about. Presumably, 12 months from now, there’ll be another one or two that are just as important,” he told The Independent.

Prof. Stephen Griffin, a virologist at Leeds University, said he believes that rather than continue to mutate indefinitely, there “will be a limit on how far the spike protein can evolve. But I’m not sure we can accurately determine what that limit may be at this point.”

Coronavirus likely to keep mutating: Scientists

https://arab.news/2y8ux

Coronavirus likely to keep mutating: Scientists

- Warning comes amid fears that new, India variant could become dominant

- Virologist: “We’re still early on in the lifetime of this virus as a human pathogen”

‘Content to die’: Afghanistan’s hunger crisis worsened by winter, aid cuts

- As winter spreads across Afghanistan’s arid landscape, work opportunities have dried up, while the wave of returning Afghans has swelled the population by a tenth, said Aylieff of WFP

- “Last year was the biggest malnutrition surge ever recorded in Afghanistan and sadly the prediction is that it’s going to get worse“

KABUL: In the dull glow of a single bulb lighting their tent on the outskirts of Kabul, Samiullah and his wife Bibi Rehana sit down to dry bread and tea, their only meal of the day, accompanied by their five children and three-month-old grandchild.

“We have reached a point where we are content with death,” said 55-year-old Samiullah, whose family, including two older sons aged 18 and 20 and their wives, is among the millions deported by neighboring Iran and Pakistan in the past year.

“Day by day, things are getting worse,” he added, after their return to a war-torn nation where the United Nations’ World Food Programme estimates 17 million battle acute hunger after massive cuts in international aid.

“Whatever happens to us has happened, but at least our children’s lives should be better.”

He was one of the returned Afghans speaking before protests in Iran sparked a massive crackdown by the clerical establishment, killing more than 2,000 in ensuing violence.

Samiullah said his family went virtually overnight from its modest home in Iran to their makeshift tent, partially propped up by rocks and rubble, after a raid by Iranian authorities led to their arrests and then deportation.

They salvaged a few belongings but were not able to carry out all their savings, which would have carried them through the winter, Samiullah added.

Reuters was unable to reach authorities in Iran for comment.

“Migrants who are newly returning to the country receive assistance as much as possible,” said Afghan administration spokesman Zabiullah Mujahid, in areas from transport to housing, health care and food.

It was impossible to eradicate poverty quickly in a country that suffered 40 years of conflict and the loss of all its revenue and resources, he added in a statement, despite an extensive rebuilding effort.

“Economic programs take time and do not have an immediate impact on people’s lives.”

The WFP says Iran and Pakistan have expelled more than 2.5 million Afghans in massive repatriation programs.

Tehran ramped up deportations last year amid a flurry of accusations that they were spying for Israel. Authorities blamed the expulsions on concerns about security and resources.

Islamabad accelerated deportations amid accusations that the Taliban was harboring militants responsible for cross-border attacks on Pakistani soil, allegations Afghanistan has denied.

NO INCOME, NO AID

As winter spreads across Afghanistan’s arid landscape, work opportunities have dried up, while the wave of returning Afghans has swelled the population by a tenth, said John Aylieff, the WFP’s country director.

“Many of these Afghans were working in Iran and Pakistan and they were sending back remittances,” he told Reuters, adding that 3 million more people now face acute hunger. “Those remittances were a lifeline for Afghanistan.”

Cuts to global programs since US President Donald Trump returned to the White House have sapped the resources of organizations such as the WFP, while other donor countries have also scaled back, putting millions at risk worldwide.

“Last year was the biggest malnutrition surge ever recorded in Afghanistan and sadly the prediction is that it’s going to get worse,” added Aylieff, estimating that 200,000 more children would suffer acute malnourishment in 2026.

At the WFP’s aid distribution site in Bamiyan, about 180 km (111 miles) from Kabul, the capital, are stacks of rice bags and jugs of palm oil, while wheelbarrows trundle in more food, but it is still too little for the long queues of people.

“I am forced to manage the winter with these supplies; sometimes we eat, sometimes we don’t,” said Zahra Ahmadi, 50, a widowed mother of eight daughters, as she received aid for the first time.

’LIFE NEVER REMAINS THE SAME’

At the Qasaba Clinic in the capital, mothers soothed their children during the wait for medicine and supplements.

“Compared to the time when there were no migrants, the number of our patients has now doubled,” said Dr. Rabia Rahimi Yadgari.

The clinic treats about 30 cases of malnutrition each day but the supplements are not sufficient to sustain the families, who previously relied on WFP aid and hospital support, she said.

Laila, 30, said her son, Abdul Rahman, showed signs of recovery after taking the supplements.

“But after some time, he loses the weight again,” she said.

After the Taliban takeover, she said, “My husband lost his (government) job, and gradually our economic situation collapsed. Life never remains the same.”

The United States led a hasty withdrawal of international forces from Afghanistan in July 2021, after 20 years of war against the Taliban, opening the doors for the Islamists to take control of Kabul.

As dusk gathers and the temperature falls, Samiullah brings in firewood and Bibi Rehama lights a stove for warmth.

“At night, when it gets very cold, my children say, ‘Father, I’m cold, I’m freezing.’ I hold them in my arms and say, ‘It’s OK.’ What choice do we have?” Samiullah said.

“(When) I worked in Iran, at least I could provide a full meal. Here, there is neither work nor livelihood.”