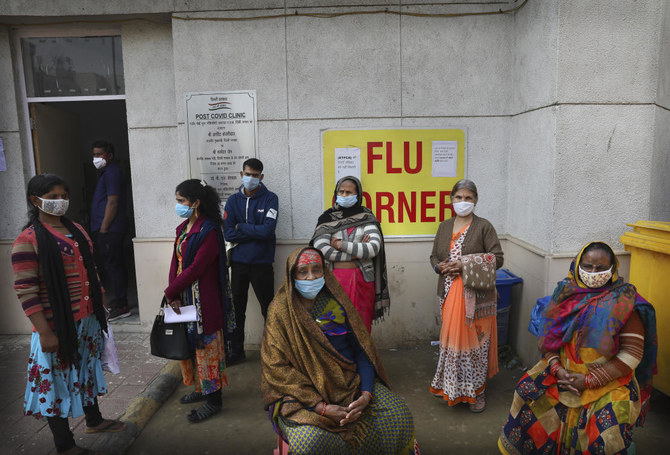

NEW DELHI: When the coronavirus pandemic took hold in India, there were fears it would sink the fragile health system of the world’s second-most populous country. Infections climbed dramatically for months and at one point India looked like it might overtake the United States as the country with the highest case toll.

But infections began to plummet in September, and now the country is reporting about 11,000 new cases a day, compared to a peak of nearly 100,000, leaving experts perplexed.

They have suggested many possible explanations for the sudden drop – seen in almost every region – including that some areas of the country may have reached herd immunity or that Indians may have some preexisting protection from the virus.

The Indian government has also partly attributed the dip in cases to mask-wearing, which is mandatory in public in India and violations draw hefty fines in some cities. But experts have noted the situation is more complicated since the decline is uniform even though mask compliance is flagging in some areas.

It’s more than just an intriguing puzzle; determining what’s behind the drop in infections could help authorities control the virus in the country, which has reported nearly 11 million cases and over 155,000 deaths. Some 2.4 million people have died worldwide.

“If we don’t know the reason, you could unknowingly be doing things that could lead to a flare-up,” said Dr. Shahid Jameel, who studies viruses at India’s Ashoka University.

India, like other countries, misses many infections, and there are questions about how it’s counting virus deaths. But the strain on the country’s hospitals has also declined in recent weeks, a further indication the virus’s spread is slowing. When recorded cases crossed 9 million in November, official figures showed nearly 90 percent of all critical care beds with ventilators in New Delhi were full. On Thursday, 16 percent of these beds were occupied.

That success can’t be attributed to vaccinations since India only began administering shots in January – but as more people get a vaccine, the outlook should look even better, though experts are also concerned about variants identified in many countries that appear to be more contagious and render some treatments and vaccines less effective.

Among the possible explanations for the fall in cases is that some large areas have reached herd immunity – the threshold at which enough people have developed immunity to the virus, by falling sick or being vaccinated, that the spread begins to slacken, said Vineeta Bal, who studies immune systems at India’s National Institute of Immunology.

But experts have cautioned that even if herd immunity in some places is partially responsible for the decline, the population as a whole remains vulnerable – and must continue to take precautions.

This is especially true because new research suggests that people who got sick with one form of the virus may be able to get infected again with a new version. Bal, for instance, pointed to a recent survey in Manaus, Brazil, that estimated that over 75 percent of people there had antibodies for the virus in October – before cases surged again in January.

“I don’t think anyone has the final answer,” she said.

And, in India, the data is not as dramatic. A nationwide screening for antibodies by Indian health agencies estimated that about 270 million, or one in five Indians, had been infected by the virus before vaccinations started – that’s far below the rate of 70 percent or higher that experts say might be the threshold for the coronavirus, though even that is not certain.

“The message is that a large proportion of the population remains vulnerable,” said Dr. Balram Bhargava, who heads India’s premier medical research body, the Indian Council of Medical Research.

But the survey offered other insight into why India’s infections might be falling. It showed that more people had been infected in India’s cities than in its villages, and that the virus was moving more slowly through the rural hinterland.

“Rural areas have lesser crowd density, people work in open spaces more and homes are much more ventilated,” said Dr. K. Srinath Reddy, president of the Public Health Foundation of India.

If some urban areas are moving closer to herd immunity – wherever that threshold lies – and are also limiting transmission through masks and physical distancing and thus are seeing falling cases, then maybe the low speed at which the virus is passing through rural India can help explain sinking numbers, suggested Reddy.

Another possibility is that many Indians are exposed to a variety of diseases throughout their lives – cholera, typhoid and tuberculosis, for instance, are prevalent – and this exposure can prime the body to mount a stronger, initial immune response to a new virus.

“If the COVID virus can be controlled in the nose and throat, before it reaches the lungs, it doesn’t become as serious. Innate immunity works at this level, by trying to reduce the viral infection and stop it from getting to the lungs,” said Jameel, of Ashoka University.

India’s dramatic fall in coronavirus cases leaves experts stumped

https://arab.news/2934d

India’s dramatic fall in coronavirus cases leaves experts stumped

- The country is reporting about 11,000 new cases a day, compared to a peak of nearly 100,000

North Korean leader Kim watches cruise missile tests with his daughter

- KCNA said the missiles hit target islands off North Korea’s west coast

SEOUL, South Korea: North Korean leader Kim Jong Un and his teenage daughter observed tests of strategic cruise missiles fired from a warship, state media reported Wednesday, as North Korea threatened responses to US-South Korean military drills.

Images sent by the Korean Central News Agency showed the two in a conference room looking at a screen showing weapons being fired from the Choe Hyon, a year-old naval destroyer.

Kim Jong Un watched the missiles launches via video on Tuesday and underscored the need to maintain “a powerful and reliable nuclear war deterrent,” KCNA reported in a dispatch that did not mention his daughter.

The girl, reportedly named Kim Ju Ae and about 13, has accompanied her father at numerous prominent events including military parades and weapons launches since late 2022. South Korea’s spy agency assessed last month Kim Jong Un was close to designating her as his heir.

KCNA said the missiles hit target islands off North Korea’s west coast. It quoted Kim Jong Un as saying the launches were meant to demonstrate the navy’s strategic offensive posture and get troops familiarized with weapons firings.

Kim Jong Un observed similar cruise missile launches from the Choe Hyon in person last week, but his daughter was not seen at that appearance.

Tuesday’s missile firings came after the start of the springtime US-South Korean military drills that North Korea views as an invasion rehearsal.

On Tuesday, Kim Jong Un’s sister and senior official, Kim Yo Jong, warned the drills reveal again the US and South Korea’s “inveterate repugnancy toward” North Korea. She said North Korea will “convince the enemies of our war deterrence.”

The 11-day Freedom Shield drill that began Monday is largely a computer-simulated command post exercise and will be accompanied by a field training program. North Korea often reacts to the two sets of training with its own weapons tests.