ISLAMABAD: Arshad Khan, the world’s most famous chaiwala, has launched his own chain of restaurants called Cafe Chaiwala Rooftop, four years after a viral photo shot him to international fame.

“Originally I thought it was pretty weird, and I was a bit shook by it,” Khan to Arab News at his new rooftop restaurant in Islamabad earlier this week. “But eventually I understood it was an opportunity I should make the most of.”

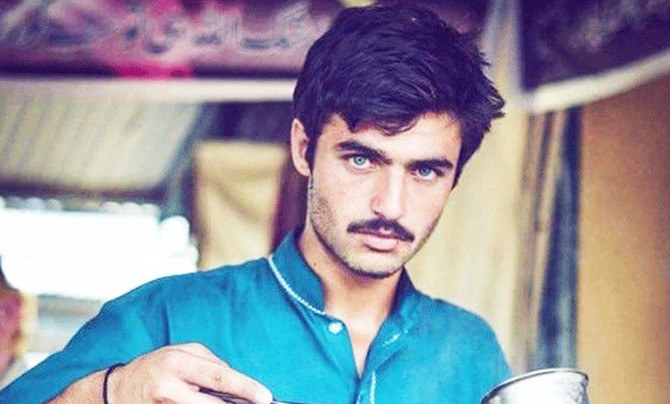

In 2016, Arshad Khan, then 18 years old, went to work, as he did every Sunday, at Islamabad’s Itwaar Bazaar (Sunday Market) where he manned a tea stall. Photographer Jiah Ali snapped a shot of the handsome young man, though neither Khan nor Ali could imagine that the photo would go viral. Shared thousands of times, Khan was dubbed “chaiwala” and showered in attention for his strikingly good looks.

Arshad Khan is making tea at a local stall in Islamabad in October 2016. The photo went viral and shot him to international fame. (Photo courtesy: Social Media)

Initially, modeling and acting offers came pouring in, but Khan was striving for stability and decided to work smart. “From the beginning, I had this idea about setting up a business that had something to do with chai since that made sense,” said Khan who learned to make tea at the age of 12 as a means to earn his living. “I am proud of the journey that brought me here. Putting chaiwala in the name was a must.”

Khan hopes to use his success to help others by building schools in the future to cater to the underprivileged communities and provide free education.

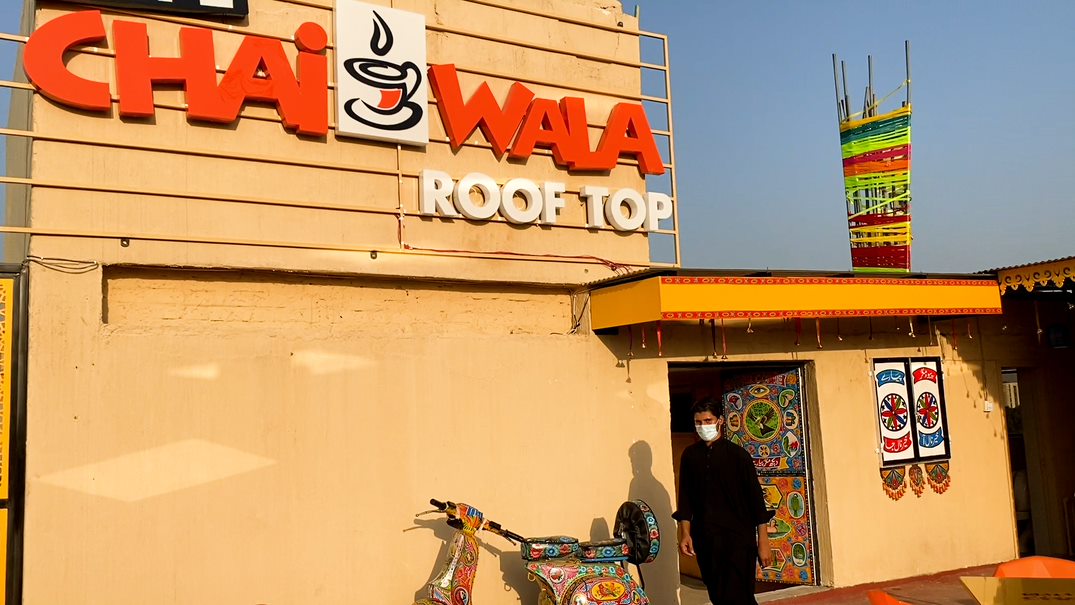

Cafe Chaiwala Rooftop belonging to Arshad Khan, the world’s most famous tea seller, is seen in Islamabad on Oct. 8, 2020. (AN photo)

In addition to Islamabad, Khan and his team are opening Cafe Chaiwala Rooftop in Murree as well and plan to further expand across Pakistan before going international. Their rooftop restaurant overlooks Islamabad’s Margalla Hills and is outfitted in truck art-inspired décor, including candy-colored table stands made of tires and lots of signs with Punjabi and Urdu puns about chai. In one of Islamabad’s busiest commercial sectors called Blue Area, it sits atop a number of offices, making it an ideal spot for people looking to grab tea and enjoy a great view after work.

As for Khan, who showed Arab News how to make a perfect karak (strong) chai, tea is not something he indulges in himself.

“I am not a big tea drinker,” he laughed. “Once a day is quite enough for me!”