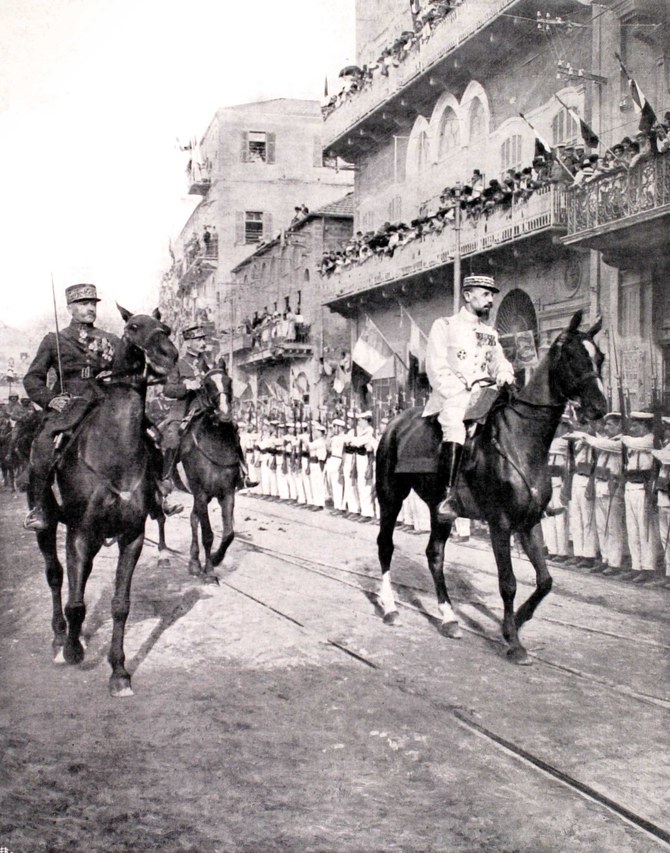

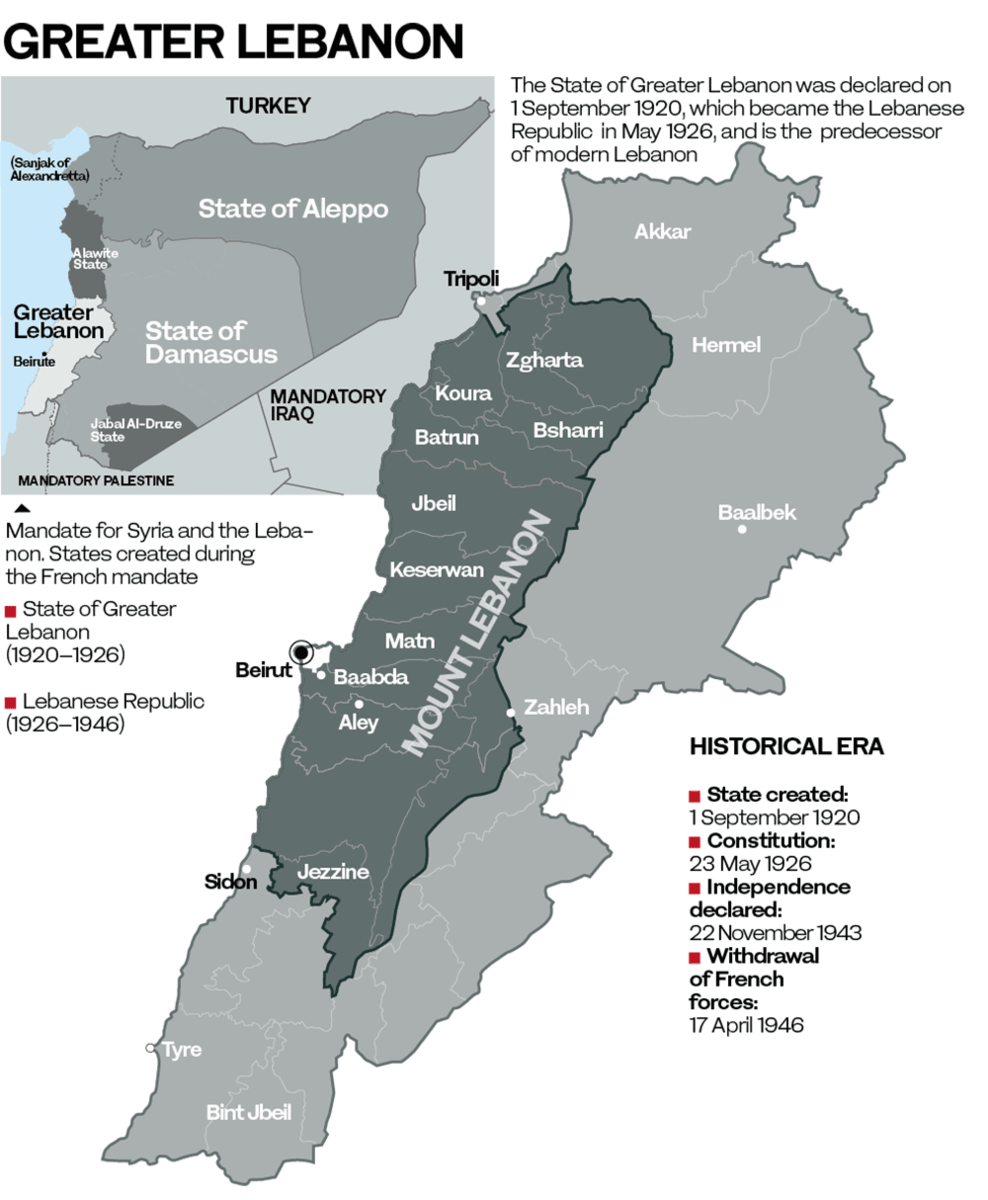

LONDON: When the League of Nations issued a decree on Aug. 31, 1920, for the creation of Greater Lebanon under a French mandate, the Arab population was reeling from years of despair under Ottoman rule, a famine that had left at least 200,000 dead and the fallout from World War I.

A century after the proclamation of the State of Greater Lebanon, a petition calling for the French mandate (originally called the Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon) to be re-implemented for a period of 10 years has attracted more than 60,000 signatures.

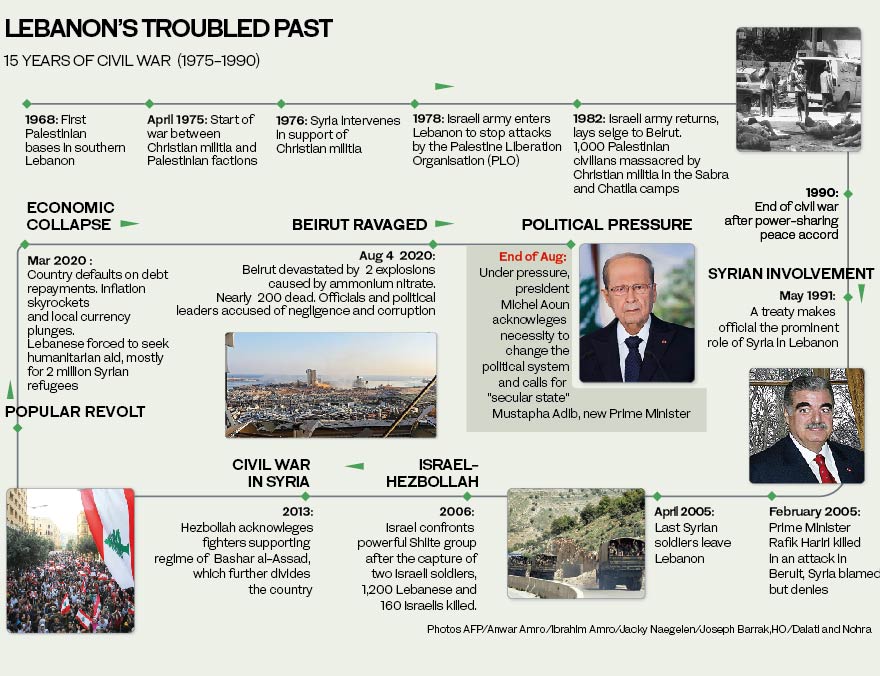

It was launched around the time French President Emmanuel Macron visited Beirut on Aug. 6, two days after 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate stored carelessly in a warehouse at the city’s port for several years exploded and damaged large sections of the city. At least 181 people died, more than 6,000 were injured and an estimated 300,000 were left homeless.

The cause of the disaster, according to most citizens, was government negligence and rampant corruption. It coincided with an unprecedented financial crisis and the deadly coronavirus pandemic. It is no surprise that many Lebanese have lost all confidence in the establishment.

“I sadly came to the realization that Lebanon, the way it is now with the government that we have, cannot run any more as an independent country,” said Marita Yaghi, a 25-year-old doctor and researcher. “Not because we don’t have the capabilities, not because we don’t have the people, but because the people who are already in the government are just so attached to their positions.

“The mandate would be there for 10 years, 1,000 per cent temporary, just to be able to help out with the transition to an independent Lebanese-led government.”

Adam Ouayda, a 22-year-old student of law at Saint Joseph University in Beirut, said: “If the mandate serves the purpose of guiding essential reforms that will allow the Lebanese state to move toward becoming a more modern state, without creating a form of economic dependency or control over Lebanon, I would be more inclined to support it.”

He added that if such a hypothetical arrangement served a strategic or military purpose that exploited Lebanon, he would oppose it.

While many among the younger generation in Lebanon agree with Yaghi about the political elite’s determination to cling to the perks of power, not all believe the solution to the problem is a temporary French mandate.

The time has come to completely rethink the way Lebanon is governed, politically and economically

Karim Emile Bitar, Director of the Institute of Political Science at Saint Joseph University

“I do not think colonization in the 21st century should be considered as a valid option because it cancels a lot of the country’s freedoms and, at the end of the day, a mandate is just colonization in disguise,” said Sara Abi Raad, a 25-year-old doctor.

Jeffrey Chalhoub, 22, agreed, saying: “Implementing the French mandate would not necessarily ameliorate Lebanon’s crises, but will add to our inability to govern and develop ourselves free from outside influence.”

Lebanon’s students and youth have been a pivotal part of the nationwide protests that began on Oct. 17 last year, calling for an end to sectarianism and corruption. Decades of government mismanagement and negligence have culminated in the country’s currency losing about 80 percent of its value.

A UN World Food Programme survey found that nearly half of Lebanese people questioned are worried they will not have enough to eat.

“I think this petition is merely a sign of despair — the Lebanese populace are so desperate, so angry and so mad at the current political system and at their ruling elites,” said Karim Emile Bitar, director of the Institute of Political Science at Saint Joseph University.

“They are so fed up with the mobsters that have been governing them for the past 30 years, that this idea — which is, frankly, completely ridiculous and unrealistic — began floating around and attracting signatures.”

The explosion on Aug. 4 and its aftermath was a wake-up call for civil-society groups across the country, he added.

“While politicians and the establishment have been completely complacent and inactive since (Macron’s) last visit, it is as if the last visit did not happen, and they have made absolutely no progress in the formation of a new government. In contrast, civil-society groups have been quite actively trying to get their act together. They have been trying to form a wide coalition,” said Bitar, who in 2017 cofounded Kulluna Irada, a civic organization advocating for political reform in Lebanon.

However, the goal of a united front to tackle the ruling elite’s grip on power has proved notoriously elusive, with different factions and civil-society groups refusing to agree or compromise on some points, including social and economic issues, early legislative elections and the disarmament of Hezbollah.

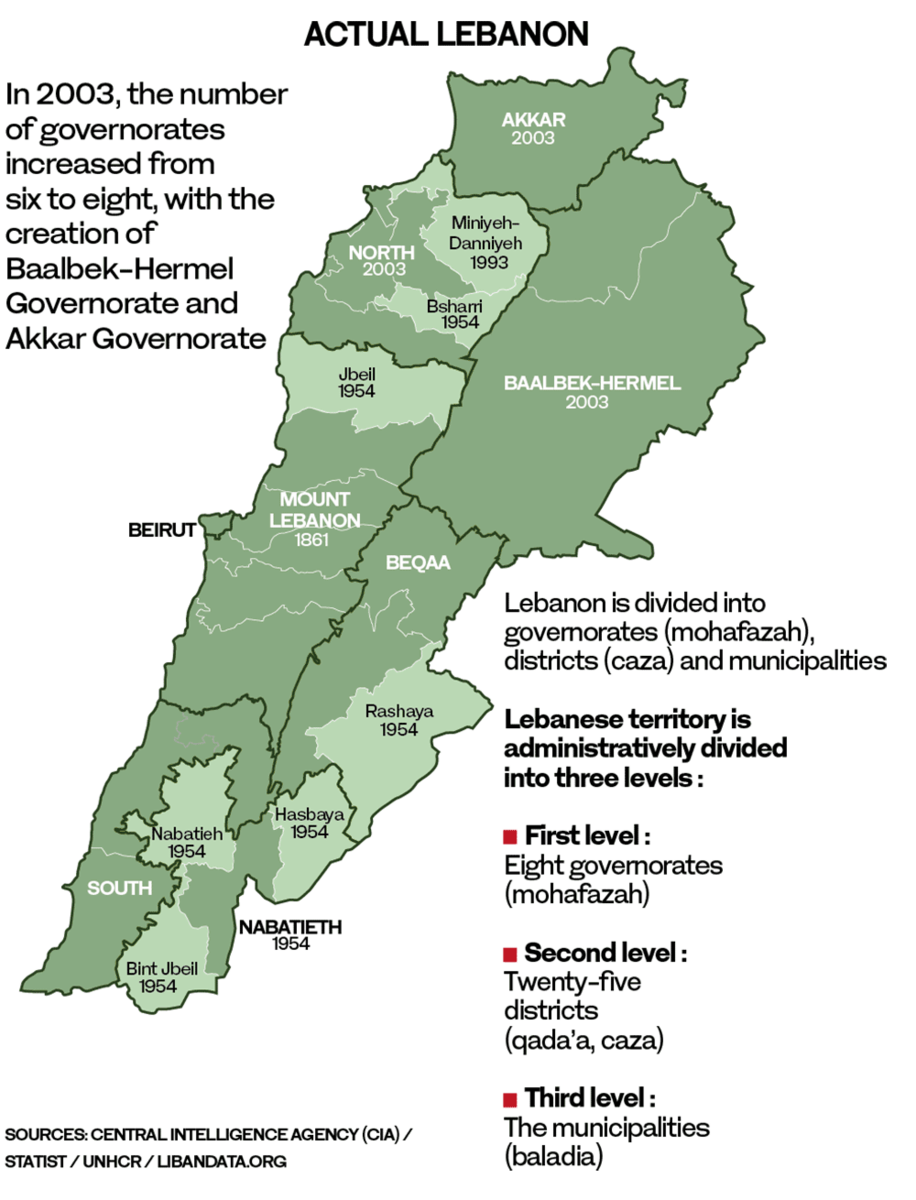

“The mutual demand today, the demand that is agreed upon by most opposition groups, is a temporary government that would have legislative prerogatives,” said Bitar. “This is not something new to Lebanon; between the 1950s and the 1980s, Lebanon had seven governments that had legislative prerogatives, and many people feel that today this would be an absolute necessity to prevent the current political parties from continuing to control what the government does, as they did under the (Prime Minister Hassan) Diab government.”

Diab’s government resigned less than a week after the explosion in Beirut but remains in place in a caretaker capacity. President Michel Aoun announced on Thursday that binding consultations would take place on Monday to decide on a new prime minister.

Analysts believe the last-minute scrambling is unlikely to bring about any genuine change and that it will be business as usual for the government. That is what happened when Saad Hariri’s cabinet resigned three weeks after the October protests began and was replaced by Diab’s Hezbollah-backed government.

“Today, Lebanon’s entire system needs an overhaul,” said Bitar. “There is a new generation of Lebanese that is demanding radical change, and the time has come to completely rethink the way Lebanon is governed, politically and economically.”

Twitter: @Tarek_AliAhmad