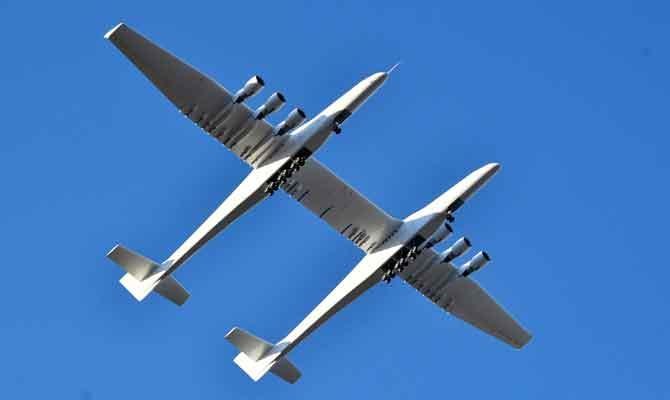

WASHINGTON: The world’s largest airplane — a Stratolaunch behemoth with two fuselages and six Boeing 747 engines — made its first test flight on Saturday in California.

The mega jet carried out its maiden voyage over the Mojave desert.

It is designed to carry into space, and drop, a rocket that would in turn ignite to deploy satellites.

It is supposed to provide a more flexible way to deploy satellites than vertical takeoff rockets because this way all you need is a long runway for takeoff.

It was built by an engineering company called Scaled Composites.

The aircraft is so big its wing span is longer than a football field, or about 1.5 times that of an Airbus A380.

Specifically, the wing span is 117 meters; that of an Airbus A380 is just under 80.

The plane flew Saturday for about two and a half hours, Stratolaunch said. Until now, it had just carried out tests on the ground.

It hit a top speed of 304 kilometers per hour (189 mph) and reached an altitude of 17,000 feet, or 5,182 meters.

“What a fantastic first flight,” said Jean Floyd, CEO of Stratolaunch.

“Today’s flight furthers our mission to provide a flexible alternative to ground launched systems,” he added.

Stratolaunch was financed by Paul Allen, a co-founder of Microsoft as a way to get into the market for launching small satellites.

But Allen died in October of last year so the future of the company is uncertain.

World’s largest plane makes first test flight

World’s largest plane makes first test flight

- The aircraft is so big its wing span is longer than a football field, or about 1.5 times that of an Airbus A380

Filipinos master disaster readiness, one roll of the dice at a time

- In a library in the Philippines, a dice rattles on the surface of a board before coming to a stop, putting one of its players straight into the path of a powerful typhoon

MANILA: In a library in the Philippines, a dice rattles on the surface of a board before coming to a stop, putting one of its players straight into the path of a powerful typhoon.

The teenagers huddled around the table leap into action, shouting instructions and acting out the correct strategies for just one of the potential catastrophes laid out in the board game called Master of Disaster.

With fewer than half of Filipinos estimated to have undertaken disaster drills or to own a first-aid kit, the game aims to boost lagging preparedness in a country ranked the most disaster-prone on earth for four years running.

“(It) features disasters we’ve been experiencing in real life for the past few months and years,” 17-year-old Ansherina Agasen told AFP, noting that flooding routinely upends life in her hometown of Valenzuela, north of Manila.

Sitting in the arc of intense seismic activity called the “Pacific Ring of Fire,” the Philippines endures daily earthquakes and is hit by an average of 20 typhoons each year.

In November, back-to-back typhoons drove flooding that killed nearly 300 people in the archipelago nation, while a 6.9-magnitude quake in late September toppled buildings and killed 79 people around the city of Cebu.

“We realized that a lot of loss of lives and destruction of property could have been avoided if people knew about basic concepts related to disaster preparedness,” Francis Macatulad, one of the game’s developers, told AFP of its inception.

The Asia Society for Social Improvement and Sustainable Transformation (ASSIST), where Macatulad heads business development, first dreamt up the game in 2013, after Super Typhoon Haiyan ravaged the central Philippines and left thousands dead.

Launched six years later, Master of Disaster has been updated this year to address more events exacerbated by human-driven climate change, such as landslides, drought and heatwaves.

More than 10,000 editions of the game, aimed at players as young as nine years old, have been distributed across the archipelago nation.

“The youth are very essential in creating this disaster resiliency mindset,” Macatulad said.

‘Keeps on getting worse’

While the Philippines has introduced disaster readiness training into its K-12 curriculum, Master of Disaster is providing a jolt of innovation, Bianca Canlas of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) told AFP.

“It’s important that it’s tactile, something that can be touched and can be seen by the eyes of the youth so they can have engagement with each other,” she said of the game.

Players roll a dice to move their pawns across the board, with each landing spot corresponding to cards containing questions or instructions to act out disaster-specific responses.

When a player is unable to fulfil a task, another can “save” them and receive a “hero token” — tallied at the end to determine a winner.

At least 27,500 deaths and economic losses of $35 billion have been attributed to extreme weather events in the past two decades, according to the 2026 Climate Risk Index.

“It just keeps on getting worse,” Canlas said, noting the lives lost in recent months.

The government is now determining if it will throw its weight behind the distribution of the game, with the sessions in Valenzuela City serving as a pilot to assess whether players find it engaging and informative.

While conceding the evidence was so far anecdotal, ASSIST’s Macatulad said he believed the game was bringing a “significant” improvement in its players’ disaster preparedness knowledge.

“Disaster is not picky. It affects from north to south. So we would like to expand this further,” Macatulad said, adding that poor communities “most vulnerable to the effects of climate change” were the priority.

“Disasters can happen to anyone,” Agasen, the teen, told AFP as the game broke up.

“As a young person, I can share the knowledge I’ve gained... with my classmates at school, with people at home, and those I’ll meet in the future.”