LONDON: With the approach of Hajj, it is all systems go at the El-Sawy travel agency in London.

Passports need to be taken to the Saudi embassy to be stamped with visas and there are myriad phone calls and emails to be made to suppliers in Saudi Arabia. Those going on their first pilgrimage — perhaps even their first long trip anywhere — will need reassurance while others who applied a little too late and missed out on a place will need placating. But from the start, one thing is obvious: You don’t get to be Britain’s oldest-established Hajj and Umrah travel agency without good people skills.

“I have also been very blessed with luck,” said the Egyptian-born travel agency owner Hamdy El-Sawy.

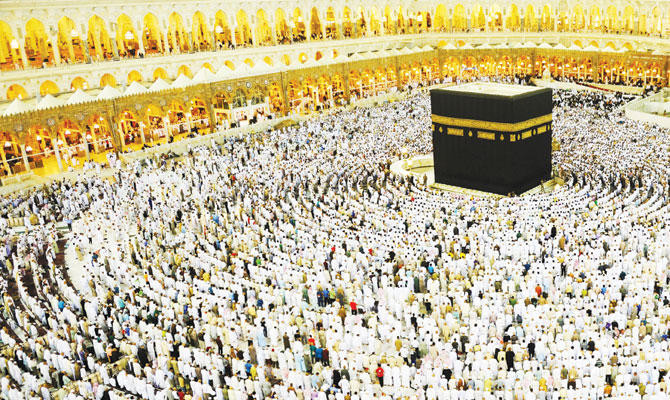

He organized his first Hajj in 1981 for 37 people. They each paid £325 and stayed in university accommodation. Lots has changed since then: This year he will accompany 150 pilgrims who have each paid £6,450 and will be based at the five-star Al-Safwah Royal Orchid Hotel. “It’s the nearest to the Haram [mosque], right next to it,” he said, pointing to a poster.

Sometimes his work involves performing quite extraordinary feats. Three years ago, an 84-year-old British publisher and convert to Islam, contacted El-Sawy a week before the group was due to leave for Hajj.

Although he was without a booking or visa, El-Sawy suggested he come along anyway to the briefing held before every Hajj.

“An official from the Saudi embassy was present. He arranged the gentleman’s visa right away, out of respect for his age. The package that year cost £4,000 but the publisher had only £2,500. By chance I got a call from another client, a well-known neurologist and convert who had been on Hajj with us. I told her the story and without hesitation she said she would cover the difference.”

Back in 1994 a woman arrived at his agency in a chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce at 7pm on a Friday. Pulling a huge wad of banknotes from her handbag, she uttered just one word: “Hajj.”

El-Sawy explained: “It was the day before we were due to leave. The Saudi embassy was closed and all the flights were full, but I couldn’t tell her any of this because the lady was from Senegal and spoke only French.”

But by chance — a phrase that crops up a lot in El-Sawy’s stories — a French-speaking client was in the office at the time. “I asked him to tell the lady ‘come tomorrow’ which, as any Egyptian will tell you, actually means ‘don’t come.’ I was fobbing her off, to be honest. But when I came to work next day, she was there again, this time in a Mercedes.

“I didn’t know what else to do so I told her driver to go to Belgrave Square [location of the Saudi embassy] and drive round it seven times and shout ‘Allahu akbar’ every time they passed the Saudi embassy. At least, she would see it was closed. I sent my office boy with her.”

She did as instructed and while she was there the security guard at the Saudi embassy noticed the circling Mercedes and came out to investigate.

“When he heard the story, he gave my office boy the number of the duty officer at the consulate. The duty officer said to bring the lady’s passport at 5pm. He did, she got her visa and went straight to the airport. But the Saudia flight, the last of the day, was full with 10 people on standby. The lady from Senegal was number 11.

“One seat came free in business class and because she was alone and everyone else ahead of her was in couples or groups, she got it, with 10 minutes to go before the flight left. The cost that year was £1,300. She gave me £2,000 in cash and gave the £700 change to the office boy.”

Another client who spoke little or no English was the Senegalese ambassador to London. In his case, El-Sawy decided to contact a client from Gambia who spoke the same African language as the ambassador and soon all the arrangements were made. On arrival in Jeddah, the ambassador received VIP treatment. “The next time we met was at a meeting of the British-Egyptian Society and he embraced me in front of everyone and said what a wonderful time he’d had.” El-Sawy would no doubt say that he came to the travel business too “by chance.” Born “in the oldest street in Cairo,” he studied commerce and law and came to the UK in 1975 and worked in accountancy, as an Arabic tour guide and translator and even, briefly, as a silver service waiter.

In 1980 he organized a day trip to Brighton on the south coast of England, to welcome the new imam at Regent’s Park mosque (El-Sawy’s local place of worship), and introduce him to his congregation.

People on the coach trip brought snacks and drinks, visited a mosque and played football on the beach and a good time was had by all. Over the next weeks, he organized more days out. On the way back from the fourth of these, to Manchester, someone asked him when he was going to do “the big one.”

And so his career as a Hajj tour operator and travel agent began. On the first pilgrimage in 1981, following another chance encounter, his group were guests of the president of King Abudulaziz University. The following year, they were accommodated at Umm Al-Qura University in Makkah. The third year, a major-general in the Saudi police hosted a group of more than 40 people at his home because El-Sawy had helped him track down a Egyptian doctor in London who had previously treated the policeman’s aged mother.

So quickly did his reputation grow that in 1989 the Swedish ambassador to Morocco, a convert to Islam, asked to join El-Sawy’s group. He didn’t want to be treated as a VIP, as he would have been if he had applied in Rabat.

“That year we stayed in military barracks and he was very happy. That gave me confidence. I realized that high-up people can be humble.”

He has frequently witnessed how the spirit of Hajj brings out the best in people, he said. In 2014, a Bangladeshi couple from London were distraught when they realized they had miscalculated and did not have enough money to pay for their 10-year-old daughter.

“I told the mother to call again. She did and by chance there was a Saudi friend of mine in the office. He heard the story and paid the difference. All he asked in return was that she say a prayer for his father.

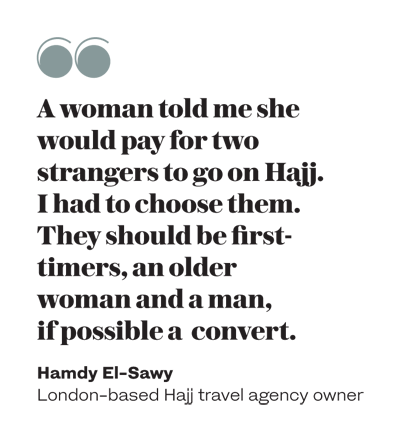

“The same year, a woman came in and told me she would pay for two strangers to go on Hajj. I had to choose them. Her conditions were that they should be first-timers, one must be an older woman and the other a man and if possible, a new convert. Thanks to that lady an elderly Moroccan woman I knew from mosque was able to fulfill the desire which she could never afford.” Even after 37 years, El-Sawy’s services are as much in demand as ever. He insists on meeting every client face-to-face and holds a get-together a week before every departure “so people can get to know each other and not feel like they are traveling with strangers.” He shows a video of last year’s briefing, and it is clear he knows everyone’s name, job and where they come from.

“His memory is incredible,” said Mustafa, 27, the younger of his two sons. “Ten minutes on the phone with him and he ends up knowing more about you than you do.”

Now 74 and with his two sons working with him, El-Sawy shows no sign of slowing down. He has mastered new technology, has an iPhoneX and continues to work all hours.

As well as the forthcoming Hajj, he is busy with an ambitious new project — a tour tracing the journey of Mary, Joseph and the infant Jesus fleeing to exile in Egypt to escape the clutches of King Herod. “I enjoy serving people,” he said. “The spiritual side of life is important and God has blessed me with a positive outlook. For me, the glass is half full.”