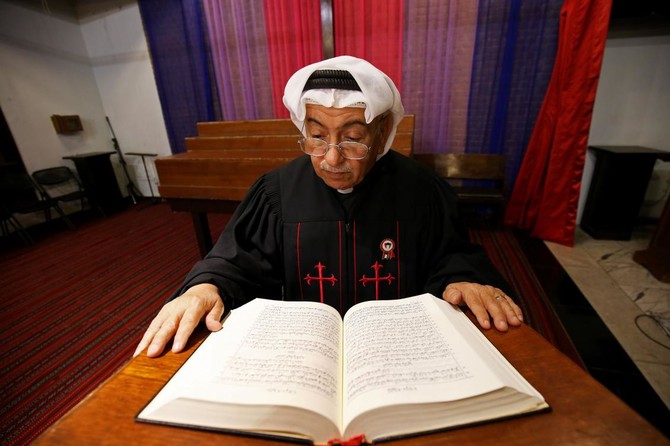

KUWAIT CITY: Dressed in a traditional white Gulf headdress and with two red crosses embroidered on his black clerical robe, Kuwait’s first homegrown priest cuts a unique figure in the predominantly Muslim emirate.

Father Emmanuel Benjamin Jacob Gharib, 68, celebrates both the Bible and Gulf Arab culture with his Christian congregation in Kuwait City.

In an interview with AFP ahead of the 20th anniversary of his ordination, he stressed the level of acceptance he has felt from fellow Kuwaitis.

“Everyone welcomes me wherever I go,” said Father Emmanuel.

Born in the Qibla district of Kuwait City, Gharib was raised in a devout Christian family and surrounded by mostly Muslim neighbors.

Like many Christian Kuwaitis, his roots lie elsewhere in the Middle East.

The priest’s father was born to an Assyrian family in southeast Turkey but forced to flee Ottoman massacres against the Armenian and Assyrian Christian minorities.

The Red Cross took his father to Iraq, where he would eventually wed Gharib’s mother — a fellow Assyrian — in the northern city of Mosul in 1945.

With the former Ottoman cities reeling from the upheaval of World War I, the couple decided to build their future in Kuwait.

They raised four girls and three boys — the eldest Emmanuel — in a religious environment, taking them to Sunday School each week.

They always felt close to their Muslim neighbors.

Priesthood

Emmanuel Gharib was not always destined for the priesthood.

He graduated from engineering school with a degree in geology in 1971 and soon found a job at the Kuwaiti oil ministry.

Ten years into his career, Emmanuel Gharib and his wife took part in a religious conference in Kuwait.

“That was the turning point,” he said. “That was where the Lord changed my life... where I was born again and began my journey with Jesus Christ.”

He quit his job and embarked in 1989 on a theology degree at the Evangelical Theological Seminary in Cairo.

He was ordained as a priest in 1999 and subsequently elected to head the National Evangelical Church of Kuwait, becoming the first and only Gulf Arab priest.

Father Emmanuel also serves as vice president of the Islamic-Christian Relations Council in Kuwait, which he co-founded in 2009.

Evangelical Church

Father Emmanuel’s own landmark next year will coincide with the 85th anniversary of the Evangelical Church in Kuwait.

But the presence of Christians in Kuwait dates back even further, to the arrival of American Evangelical missionaries and the founding of the American Mission Hospital in the early 1900s, he said.

Kuwaiti “society began to have a positive view of the missionaries during the Battle of Jahra because the Mission Hospital played a big role in treating the wounded,” Father Emmanuel said, referring to Kuwait’s 1920 battle against Saudi-backed Wahhabi militants.

Over the past century, Christians have immigrated from Turkey, Iraq and Palestine during periods of upheaval, gaining citizenship under a 1959 Nationality Law, although a later law banned non-Muslims from naturalization.

At the last count, according to Father Emmanuel, Kuwait has 264 native Christians from eight extended families, out of a total native population of 1.35 million.

The local Christian population is dwarfed by 900,000 expatriate workers of various Christian denominations and nationalities — from Lebanese to Filipinos.

Unlike Saudi Arabia which bans the construction of churches, Christians of different denominations are “free to practice” in several churches and Kuwait City municipality has provided land to bury their dead, he said.

Christian Kuwaitis say they feel a greater sense of identification with one of their own as priest.

“An Egyptian or Lebanese priest performs the same liturgy but a Kuwaiti priest can communicate the teachings of the Bible in the Kuwaiti dialect,” said Abu Nader, a 63-year-old parishioner.

For 54-year-old Eyad Noman: “Our relationship with him is very strong... He is one of us.”